The Missed Turn: A Victim of Doping, Allison Wagner Deserves Greater Recognition

This month, Swimming World debuts a new series titled, “The Missed Turn.” In this bi-monthly segment, we will examine the career of an athlete who – for one reason or another – has not received his/her proper due. The feature’s title is not a reflection on the athlete. Rather, it suggests that the sport has missed out on – and underappreciates – the excellence delivered by this individual. And now, it is time to celebrate what he/she has accomplished.

**************************************

In our sport, Olympic gold is the ultimate award. In the chase for that peak achievement, any number of factors can determine whether the mountain is scaled. Obviously, skill is the primary consideration. Timing often plays a role. So does health. The opposition, too, has a major influence, for occasionally, a specific foe might not be beatable.

Allison Wagner ran into another obstacle.

The impact of the systematic-doping program of East Germany is a well-known black eye on the history of the sport. Stars such as American Shirley Babashoff and Dutchwoman Enith Brigitha were denied their rightful honors – individual Olympic crowns. They were also thwarted at the World Championships, as their opposition didn’t rely merely on talent, but also on the boost supplied by the little blue pill known as Oral-Turinabol.

By the time Wagner emerged as one of the United States premier performers in the individual medley events, the Berlin Wall had come down, and the East German doping program was no more. Did that mean the sport was clean? Hardly, and Wagner learned that truth – perhaps – in a harsher manner than anyone on a pool deck.

A rising star on the American scene, Wagner emerged on the global stage at the 1993 World Short Course Championships in Spain. In Palma de Mallorca, Wagner captured a gold medal in the 200 individual medley and a silver medal in the 400 I.M., the shorter event producing a world record that endured for nearly 15 years. In retrospect, what unfolded in the 400 medley served as a harbinger of what was to come.

At the inaugural World Short Course Champs, Wagner’s silver in the 400 I.M. arrived behind China’s Dai Guohong, who set a world record en route to a two-second triumph over the American. Although Dai did not test positive for a banned substance, China had suddenly emerged as a global power in the pool, the use of performance-enhancing drugs thought to be the driving force. In a way, East Germany had been replaced by another rogue nation.

A year later, Wagner’s misfortunes continued.

At the 1994 World Championships in Rome, China’s power was on full display. In addition to notching victories in 12 of the 16 women’s events, the Chinese swept the relays and managed three gold-silver finishes. Wagner left Rome with silver medals in the 200 I.M. and 400 I.M., beaten by Lu Bin in the shorter distance and Dai again over 400 meters. What was unfolding, especially against the backdrop of past East German dominance, did not sit well.

“I believe you have to be incredibly naive to ignore the circumstantial evidence,” said Dennis Pursley, the National Team Director of USA Swimming. “The current situation is an exact replica of the GDR, and it is depriving deserving athletes of the attention and success they deserve. We can’t put our heads in the sand again and pretend what we know is happening isn’t happening. Our athletes just aren’t buying it this time. Common sense tells you that our athletes aren’t going to make the major sacrifices required to compete at this level when they know the deck is stacked against them.”

In the months following the 1994 World Champs, China’s thinly veiled secret was revealed as several athletes failed doping tests, including Lu. Still, Wagner was left as the silver medalist in each of her events as she prepared to race at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. On home soil, the Americans would not have to deal with drug-fueled China, although Wagner would be greeted by another unfair hurdle.

As a 1988 and 1992 Irish Olympian, Michelle Smith was an also-ran in worldwide competition. Yet, on the road to the 1996 Olympics, questions arose concerning Smith’s metamorphosis to Olympic-title contender. She first emerged from the shadows to capture multiple European titles in 1995 and her drops in time mimicked what is seen in an age-grouper who has just entered the sport.

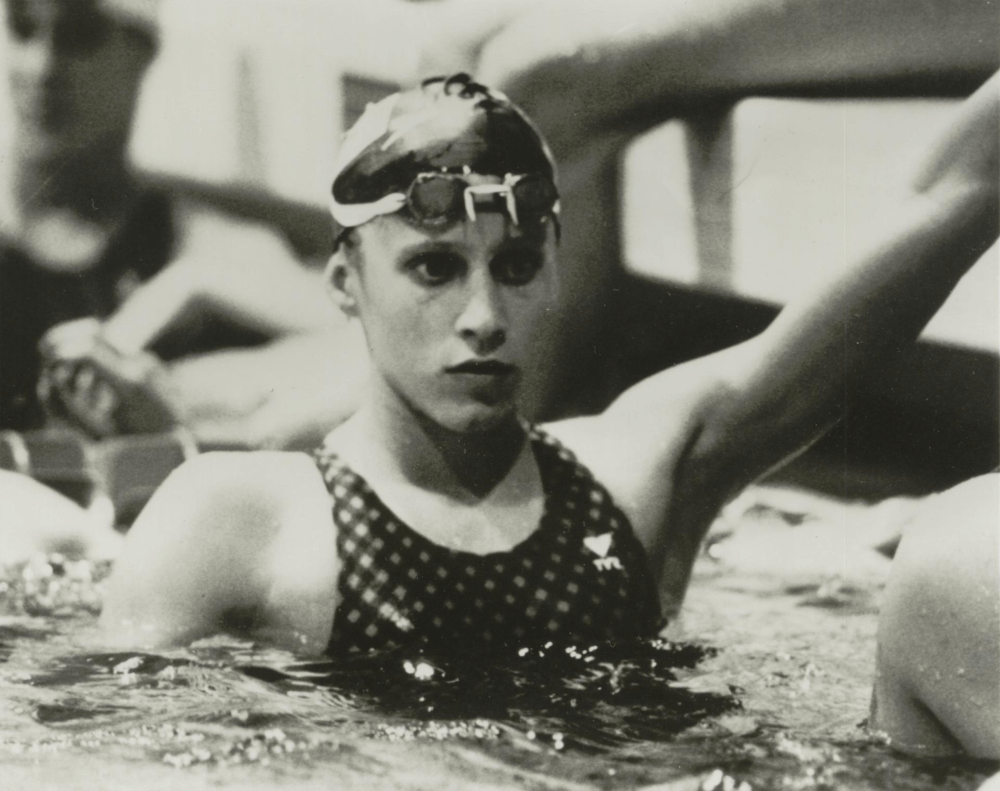

Photo Courtesy: Peter Bick

At the Atlanta Games, Smith was the star of the women’s competition, securing gold medals in the 200 I.M., 400 I.M. and 400 freestyle. For good measure, she won a bronze medal in the 200 butterfly. It was in the 400 medley in which Smith denied Wagner her proper place on the podium. While Smith clocked 4:39.18 for the gold medal, Wagner touched in 4:42.03 for the silver medal. Once again, the American was beaten by an opponent suspected of doping.

Although Smith brushed aside the accusations of performance-enhancing drug use and Ireland accused the United States of sour grapes, the truth surrounding Smith was revealed in 1998. Just two years after attaining disputed Olympic glory, the Irish lass tampered with an out-of-competition urine sample. The result of that move was a four-year ban from the sport. Nonetheless, Smith maintained possession of her four Olympic medals, including the gold in the 400 I.M. that should have gone to Wagner.

“The Olympics are a big part of anyone’s life,” Wagner said after Smith’s doping ban. “This decision has not closed a chapter in my life. Not at all. The decision won’t bring any closure at all to me. It is reassuring, but it doesn’t change anything for me. Thirty years from now, she will show her grandchildren her gold medal. I will show my grandchildren silver. She has those gold medals in her possession. She will always have gold and I will always have silver. It will always be that way forever.”

In what is a fitting role, Wagner currently works as the Director of Athlete and International Relations for the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). The position enables Wagner to serve athlete needs with USADA. Unfortunately, she does not possess the gold medal from the 1996 Olympics that should be in her medal collection, or hang on her wall. More, Wagner is missing as an inductee from the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

A comparison can be drawn between Wagner and Craig Beardsley, the former world-record holder in the 200 butterfly. As 1980 dawned, Beardsley was the overwhelming favorite for gold in the 200 fly at the approaching Olympic Games in Moscow. Ultimately, Beardsley did not receive the opportunity to chase that title, due to the United States’ boycott of Moscow in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. The lack of a gold medal for Beardsley, like Wagner, has seemingly been the missing piece to ISHOF entry. Sadly, neither athlete could control what transpired.

Allison Wagner will forever be known as an NCAA, national and world titlist whose wide-ranging skill set served her perfectly in the medley disciplines. Unfortunately, though, her grandest moment never came to fruition, stolen by a drug cheat. So, it is important to look back, tip the cap to her and continually ensure Wagner’s days in the pool are respected and appreciated.