[ad_1]

Revisiting the theme of analysing matches from previous seasons but not too long ago to be called a ‘retro analysis’, I planned on analysing Chelsea’s first match against Manchester City in the season they won the title under Antonio Conte.

Much to my dismay, author JD had already written a good analysis of the match – I was just a few years too late. Instead, I settled for Chelsea’s game just before against Mauricio Pochettino’s Tottenham Hotspur. It proved to be a good choice, not only because I avoided being accused of plagiarism, but it also proved to be an interesting match-up.

This analysis will discuss a number of elements in the game, but will mainly be structured into two sections:

- Chelsea’s solutions to Tottenham’s high pressing strategy

- Tottenham’s approach in possession against Chelsea’s midfield press and in the final third

Within these sections, I will use the first two goals in particular to discuss some wider theoretical points.

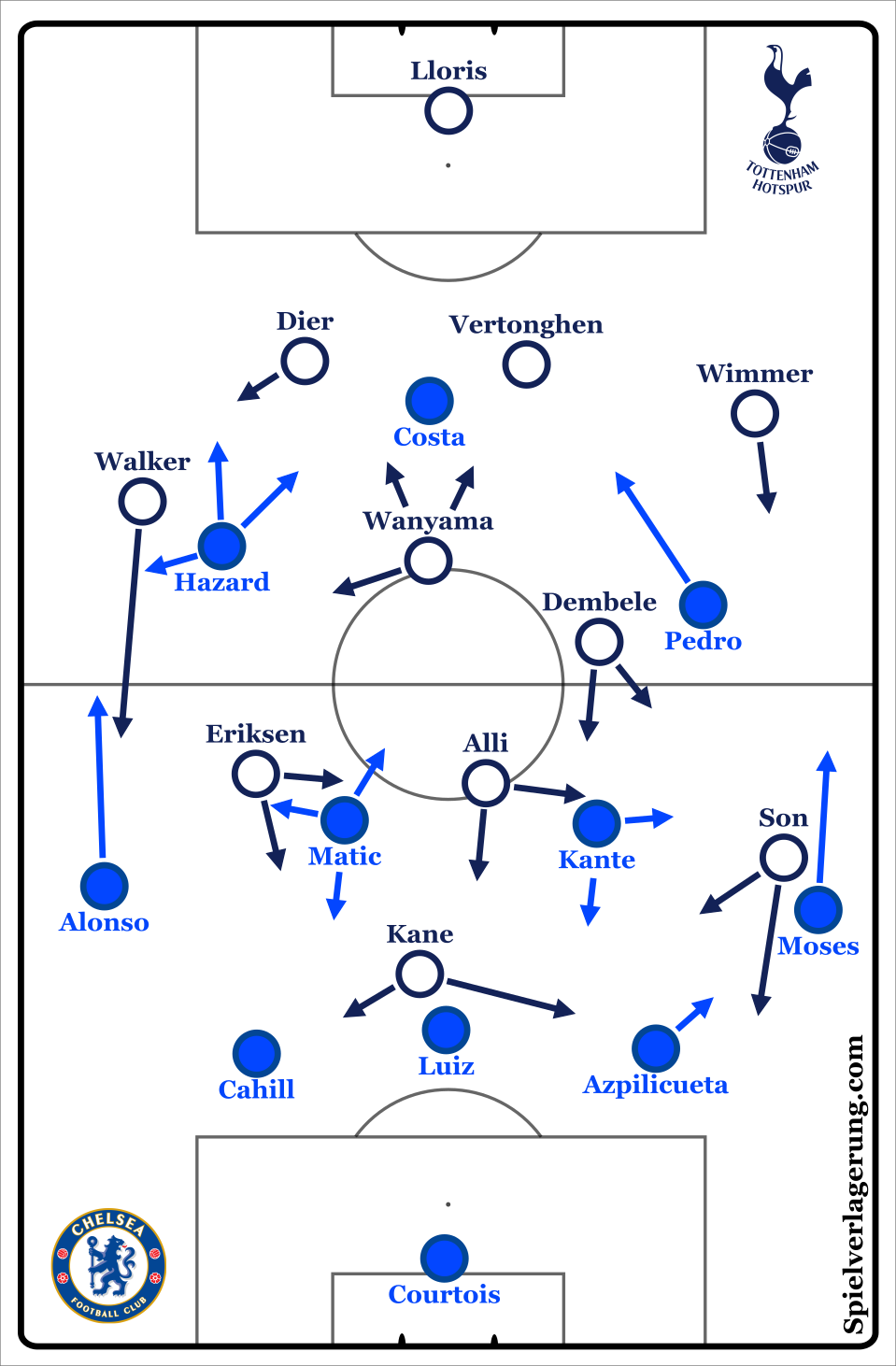

Tottenham Attempt to Press in a Diamond

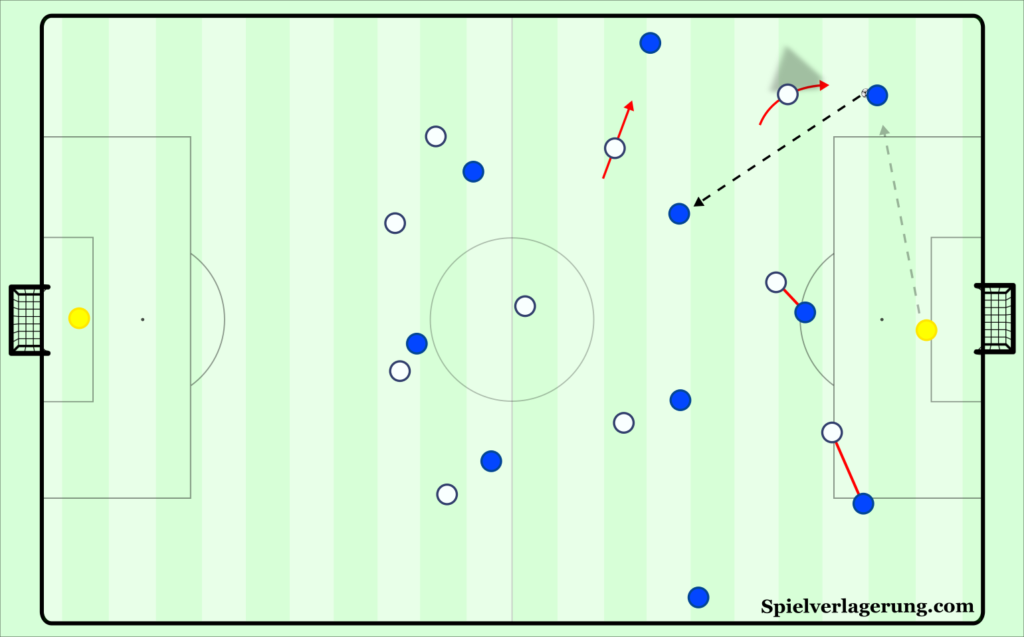

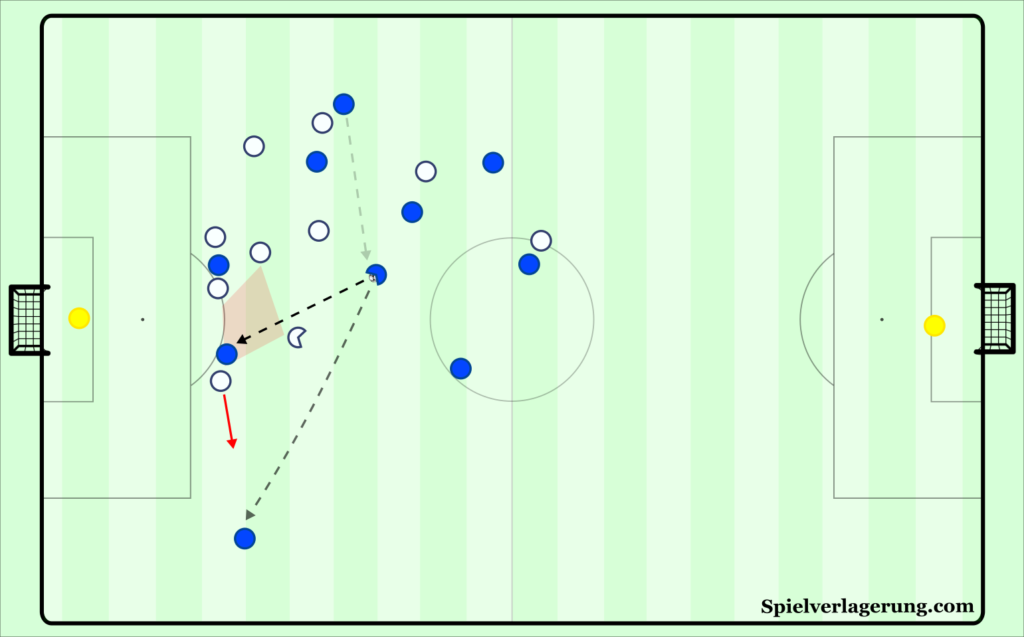

Tottenham looked to press Chelsea in a 4-diamond-2 shape which was lopsided from their original 4-2-3-1. The front two was left winger Son while Kane moved towards Cahill and Dele occupied David Luiz. In midfield, Christian Eriksen dropped into position of a right central midfielder with Mousa Dembélé taking the left eight and Wanyama as a pivot.

Their idea was to press Chelsea to one side from structured situations. The home side mainly played to Azpilicueta – it was quite surprising that Son didn’t have a higher starting position on the left to force them to play through Cahill instead. While Eden Hazard was on Cahill’s side, showing the ball down this side initially may have allowed Tottenham to shift across and defend the Belgian if he received while limiting pass receptions to straight, longer passes.

Anyway, once the ball moved to Azpilicueta, Son would press while mainly looking to cut-off the wing-back option while Dele and Kane restricted circulation back inside through Luiz. Mousa Dembélé would be in a position to press Victor Moses while being relatively close to Kanté as Wanyama and Eriksen covered across from ball-far spaces. If the pass to Kanté could initially be prevented then Dele and Kane would shift around so that Dele could be positioned between Kanté and Luiz, while Kane would be between Luiz and Cahill. They would still stop Chelsea from circulating back inside but have a more flexible position to cover the different options (including Kanté) as well as Kane being in a better position to press the back-pass to the goalkeeper.

This structure also allowed Son to be higher for counter-attacking opportunities. Upon regaining the ball, they immediately had a target player with Kane while Dele was close-by for lay-offs. Their most dangerous threat was through their left winger, who would typically be available in space between Moses and Azpilicueta once Chelsea turned the ball over. While Kane was there to receive passes, Son was another good outlet for balls into space on the left.

Pressing from Unstructured States

Of course, Tottenham didn’t only press from structured situations. When they attempted to press in more transitional moments, their shape naturally resembled more of a 4-2-3-1 / 4-4-2 with Eriksen and Son on the same lines. Such a structure relied heavily on the front two being able to simultaneously apply pressure on Chelsea’s first line while screening passes into both pivots. It was clear to see why this wasn’t chosen as Tottenham’s main pressing structure.

If the front two tried to press Chelsea’s first line then they would usually leave the pivots free, forcing Wanyama and Dembélé to step up and leave the midfield exposed. If they didn’t press, then Conte’s side would circulate across and progress down the outside of the block through Azpilicueta moving wider, separating himself from Son and creating the pass down the line to Moses.

Chelsea’s Solutions

Find Kanté Between Son and Dele

Mousa Dembélé’s poor interpretation of his option-oriented role allowed Chelsea to play through the press in the first few instances and find Kanté between the lines. In his position between Kanté and Moses, Mousa Dembélé got his distances wrong in the first few attempts at a high press. The Belgian moved too early towards Chelsea’s wing-back despite Son covering that pass quite well. His over-anticipation of Moses receiving meant that Kanté was left free in an open lane before Dele could shift across.

When Kanté did receive, his main follow-up options were to play into the feet of a forward or switch play to the ball-far wing-back. Either way, the team intention was the same. If the ball went into Costa, the only intention was to ‘collapse’ the defence à la Basketball – forcing Walker to come further inside to give Alonso more space to receive on the wing. As an overall strategy, Chelsea showed a clear intention to exploit ball-far spaces as Tottenham shifted across so closely to the ball, a clear mark of their team without the ball under Pochettino (while also being a trademark of Conte’s side).

To try and limit these situations where Kanté received in space, Tottenham showed three adaptions to their dilemma – highlighting their adaptability in pressing.

a) Wanyama was given the unenviable task of stepping up onto Kanté – a sizable distance but achieved through early communication from Pochettino and his physicality to quickly close the gap. He was able to stop Kanté from turning, but the downside was that this would leave space in front of the defensive line. Chelsea looked to access these spaces with Kanté laying the ball off for a teammate to make a chipped pass into Diego Costa with the wingers inside for lay-offs or flick-ons.

b) Son would instead press Azpilicueta while screening the pass into Kanté, allowing the pass down the line to Moses. Since Kanté was screened, Dembélé was able to move towards the wing-back earlier and press Moses as he received the ball. It was clear that this was intentional as Son would often direct Dembélé behind him through pointing. Tottenham defended this situation fairly well, the normal follow-up pass into Kanté was blocked by Dele shifting backwards onto the Frenchman. The other option into Pedro was covered by Dembélé screening with his cover shadow and Wimmer staying tight to the man.

c) If these two solutions weren’t possible, then Dele had to backwards press the Frenchman while screening the backwards option of Luiz. Although this couldn’t necessarily stop him playing forwards, and thus was the ‘last-resort’, it at least reduced his possible time on the ball to take advantage of the space.

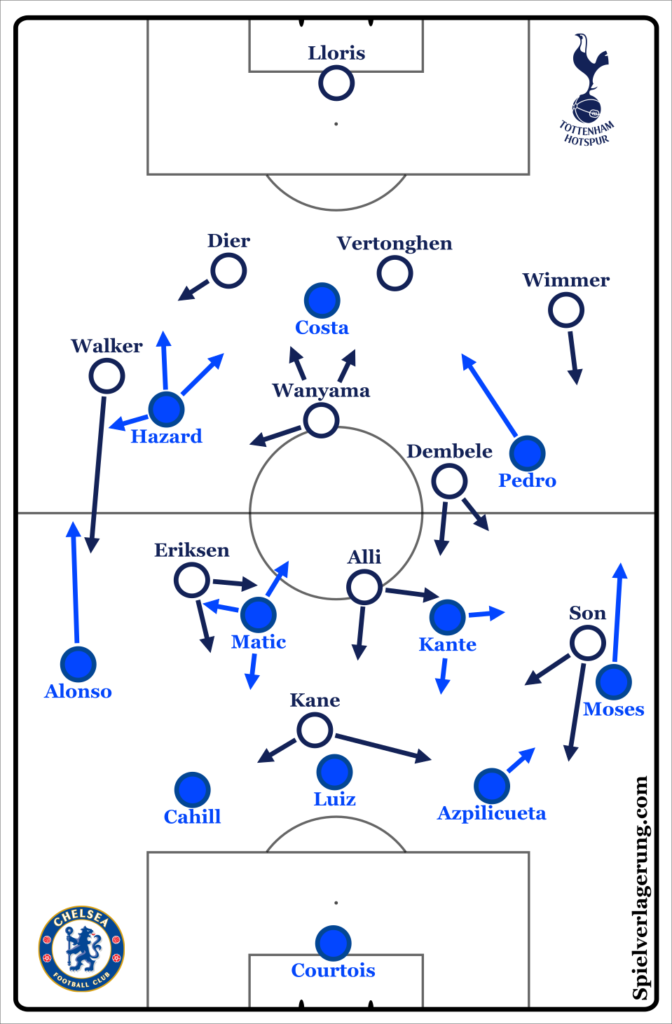

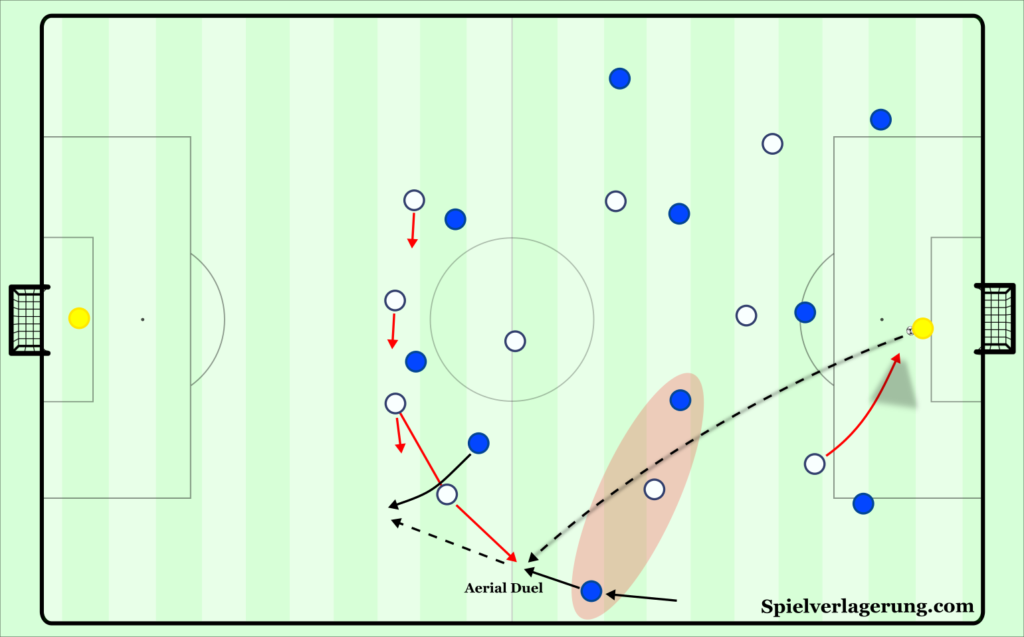

Clipped Passes onto Alonso

Given Tottenham’s flexibility to covering Kanté after the early couple of mistakes, Chelsea more consistently looked to play clipped passes onto their wing-backs. How they utilised their wing-backs presents a nice opportunity to compare to my previous analysis, where Hoffenheim freed their wing-back on the ball against Liverpool to then have in-behind or penetrative passes as follow-up actions.

In comparison, Chelsea looked to play onto the wing-back for aerial duels. They mainly played to Marcos Alonso their left side for a few simple personnel reasons:

- Alonso had a height advantage in the duel over Walker, of course helping to win the first ball more often. Compare that to the right side where it was Victor Moses against Kevin Wimmer, and the point is obvious.

- With Eriksen on that side for Tottenham, he offered less defensive support on the left than Mousa Dembélé. Firstly, he wasn’t going to get into the aerial duel itself (which Alonso would have dominated but allowed Walker to cover Hazard) and wasn’t going to be as effective in second ball situations.

- Finally, Eden Hazard was on the left too. If Courtois was to play a clip onto Alonso, who would be going into an aerial duel against Kyle Walker, then it’s possible that Hazard would be free to win the flick-on. With Eric Dier shifting across, the Belgian typically had time to turn and face his defender and run with space to manoeuvre.

The difference in how Chelsea’s setup facilitated this direct play was clear, especially when you compare it to Hoffenheim’s setup against Liverpool.

Marcos Alonso’s positioning was higher than Steven Zuber for Hoffenheim. Nagelsmann looked for his wing-back to receive to feet and thus wanted to create a distance between him and his pressers. Since Conte wanted to exploit an aerial duel against Walker, Alonso stayed higher so the duel was made high on the pitch and close to Hazard. For Hazard, there was clearly no intention for him to pin defenders – instead he looked to receive behind Walker as the defender goes into the aerial duel against Alonso. Inside, Matic didn’t necessarily adjust his positioning, but his presence made that Christian Eriksen was positioned slightly narrower.

Much like Hoffenheim, Chelsea’s strategy was effective – in their case in getting Hazard on the ball in space. Given Costa’s presence between the centre-backs, Dier was reluctant to go directly to Hazard (who is already good with pressure on his back) and leave the last line exposed man-for-man. As was the strength for Chelsea and the open space from Tottenham, Hazard would look to dribble inside and play a switch to Moses running from deep. Because of Son’s high position in the pressing, the Nigerian would typically be free while Pedro’s outside-to-inside runs would pull Kevin Wimmer inside.

Including these long passes onto Alonso, Chelsea were more than content to take a more direct approach to build-up after the first 15 minutes. Pochettino’s side were able to make a couple of high regains and in general looked good for their 1-0 win. With a good target player in Costa and the aforementioned setup with Marcos Alonso, Conte setup his team to have two good options to play over Tottenham’s press.

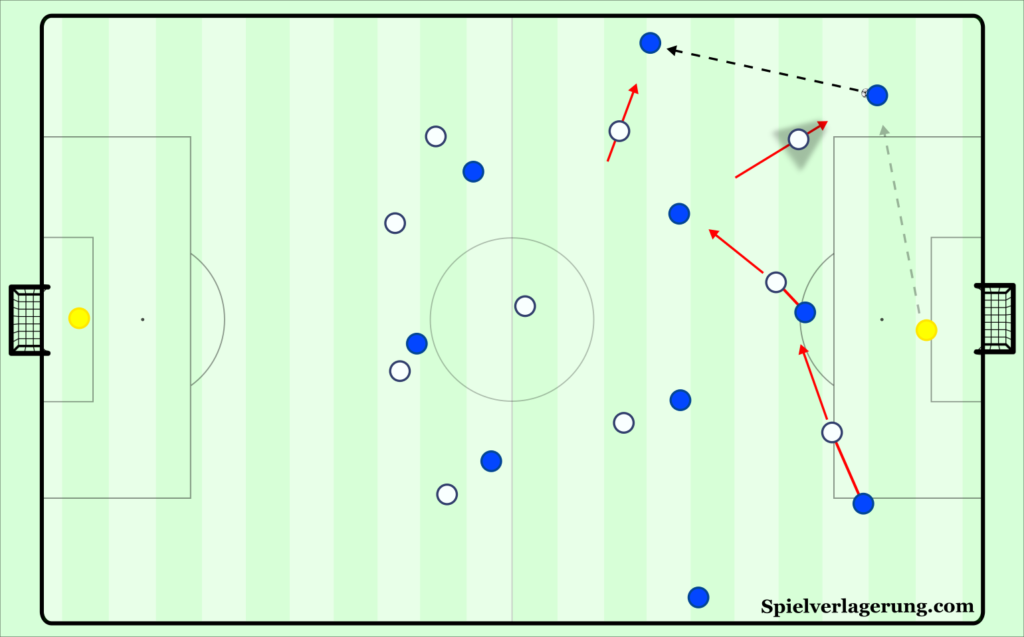

Chelsea’s Equaliser – Theoretical Tangent on Switching Play

As I have mentioned, Chelsea often looked to progress the attack into the final third via switches, a trademark Conte’s 3-4-3 system.

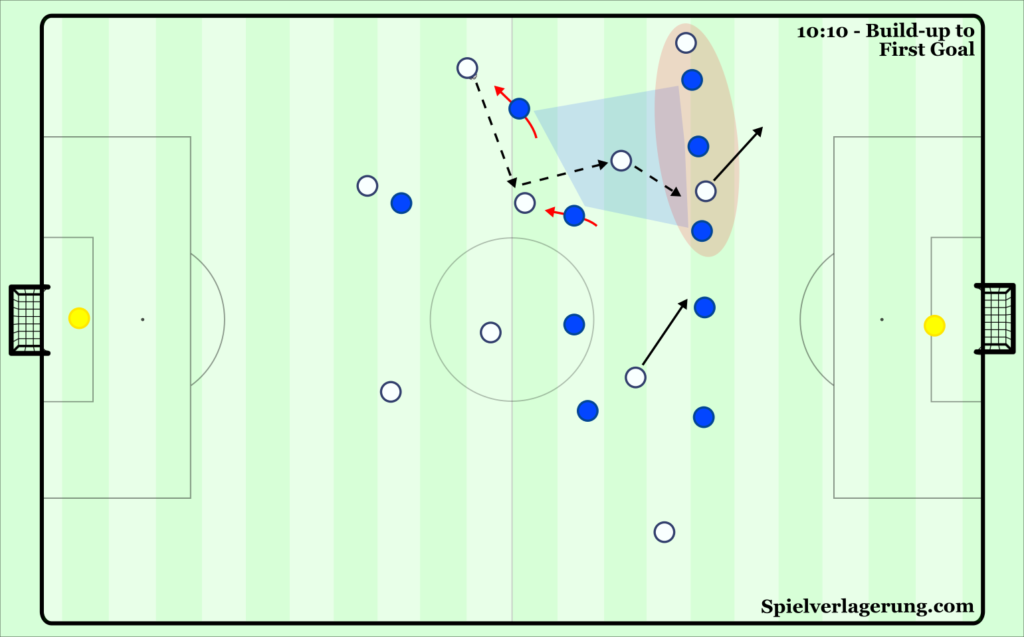

Those switches of play were key in the build-up to their equaliser, but not in the way you would expect. When Chelsea switched play, they rarely did so with a single long pass and instead made two or three medium-to-shorter passes to access the ball-far wing-back in space. Compared to longer switches, this would mean that the ball might take slightly longer to reach the opposite side of the pitch but there are other benefits to switching with multiple passes which completely outweigh this disadvantage.

With a direct switch of play, the ball has a long and unchanging trajectory, so the defending team know where the ball will be received and can adjust as soon as the ball is played, if not before. Contrast that with switches of multiple passes. With each player that the ball is switched to, the recipient has the option to continue the switch of course, but he also has the opportunity to play in other directions – for example back to where the ball came from or between the lines of defence.

On this basis, although a direct switch typically would take fewer seconds to reach its target, a switch of multiple passes can be quicker in relation to the opposition’s shifting, which really is what we want, right?

This is because the defenders cannot over-anticipate the switch in case the player on the ball decides to play in a different direction. So as opposed to a direct switch where they can sprint across the pitch if they’d like, they have to shift with caution of each pass across the field. Given that the player who can change the direction is in the centre of the pitch, he can have many options available to him as he is in range of the entire width of the field. In his analysis of Conte’s Chelsea, author JD explains how this can increase the space available to the ball-far wing-back, as the central position forces the wider player to come inside and protect the middle.

“Since the centre of the pitch provides the quickest route to goal it is the immediate priority of defensive teams. Therefore when a team are able to play through central areas opposing wide players can be drawn infield to press whilst the ball goes out wide into the space they leave. This ability to “mis-direct” an opposing defence (go against the grain) is crucial and is a tool for creating time and space on the ball.“

For Chelsea’s equaliser, the same principle of “mis-directing” the opponent occurred but in the opposite manner.

When Matić received the ball in the centre, both Diego Costa, Pedro and indeed Antonio Conte were directing the Serbian to continue the switch outside to Marcos Alonso in space. Anticipating this next action, Kyle Walker left his position immediately and began to shuffle quickly towards the outside of the pitch to ensure the Spaniard received in less space. However, doing so meant that he left Pedro completely free on the edge of the box and Matic found him expertly with a reverse pass.

The goal was a perfect example of why switches with multiple passes can be more dangerous than direct ones, as the attacking team can change the direction of the play at intervals in the centre of the pitch.

It allows the attack to exploit any defensive over-anticipation of a passing option for the player on the ball. In general, the player on the ball can play the option that the defender provides you. Ideally, this is the space inside as Walker allowed Matić to find but as JD said, if they (more likely) close the centre, then you can increase the space wide for the wing-back.

This is especially the case in moments such as the goal – when there is no pressure on the switching player. If a defender was pressing Matić, he could be able to limit the options and also make him play the ball quicker, making it easier for the defenders to anticipate the next action as the possibilities are reduced. Without pressure, Matic has more options to pass to and can make the pass at any time, making the situation more unpredictable for covering defenders. This situation leads to more over-anticipation from these deeper defenders as Walker showed in this instance.

Related tweets from JD above.

As a final point, since any switch requires the defending team to quickly shift across to be able to defend the other side of the pitch, it gives the attacking team the opportunity to play against the direction of the opponents’ shifting and exploit counterdynamic.

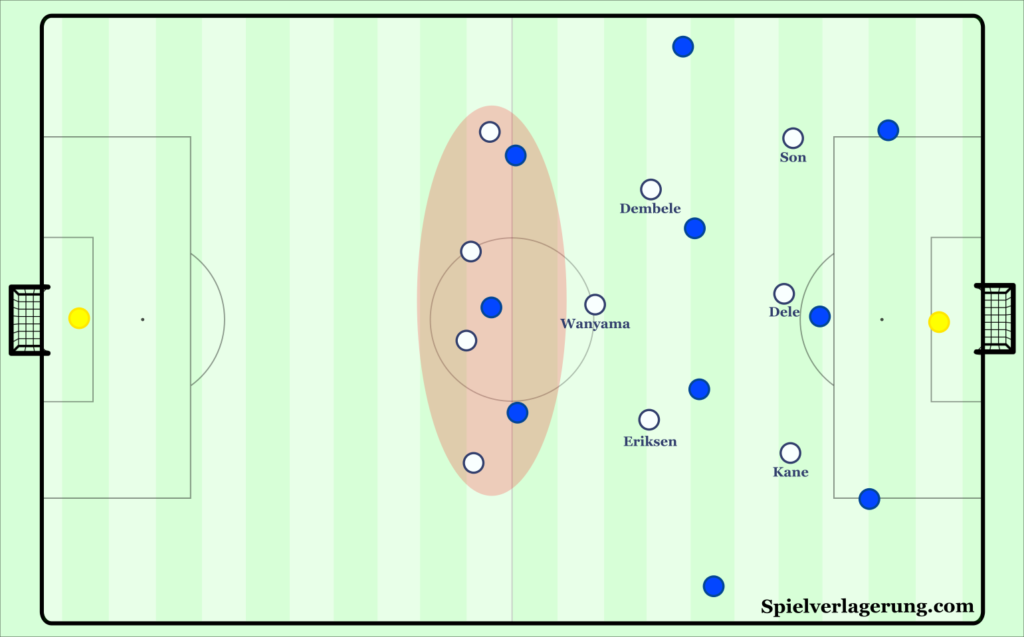

Tottenham against Midfield Press

Like Tottenham’s pressing structure was lopsided, they also used an asymmetrical shape when in possession of the ball. Right-back Kyle Walker usually moved into a high and wide position while left-back Kevin Wimmer stayed deeper and either in line with the centre-backs or the pivot. The two wingers balanced these movements, with Son Heung-Min high and wide on the left and Christian Eriksen inside on the right to occupy the 10 space alongside Dele. Mousa Dembélé acted slightly higher than Wanyama in the left half-space but stayed in front of Chelsea’s midfield line and connected to his midfield partner. The result was a 3-box-3 structure.

Through Wimmer’s deep position (I really can’t escape deep full-backs, huh?), Tottenham looked to stabilise possession by restricting Chelsea’s ability to press from their midfield block given their narrow midfield four. In their first few possessions, they seemed to take a low risk approach and hit long diagonal balls to Kyle Walker which weren’t effective.

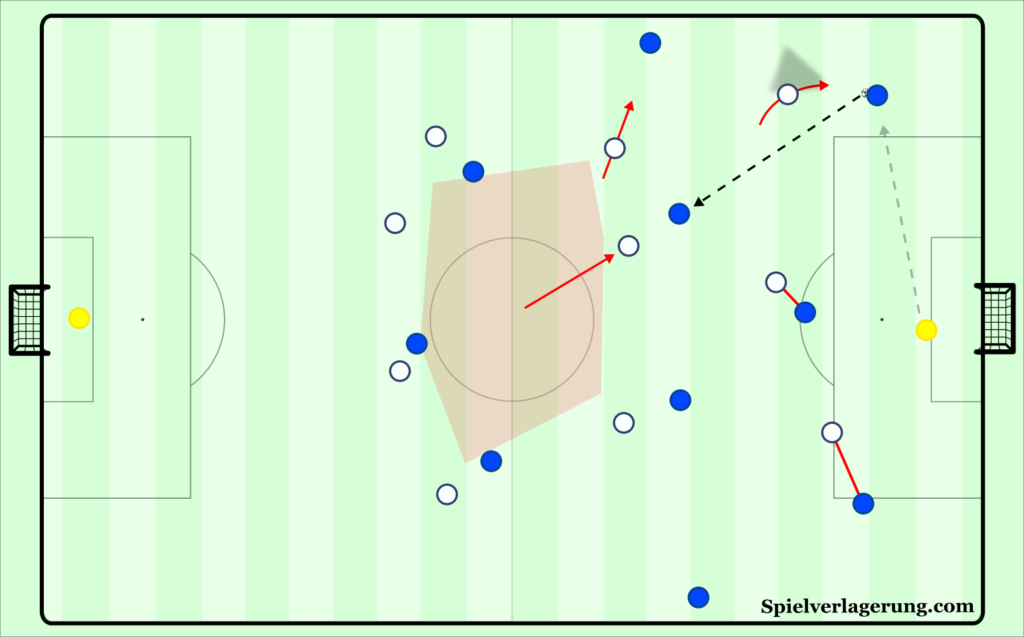

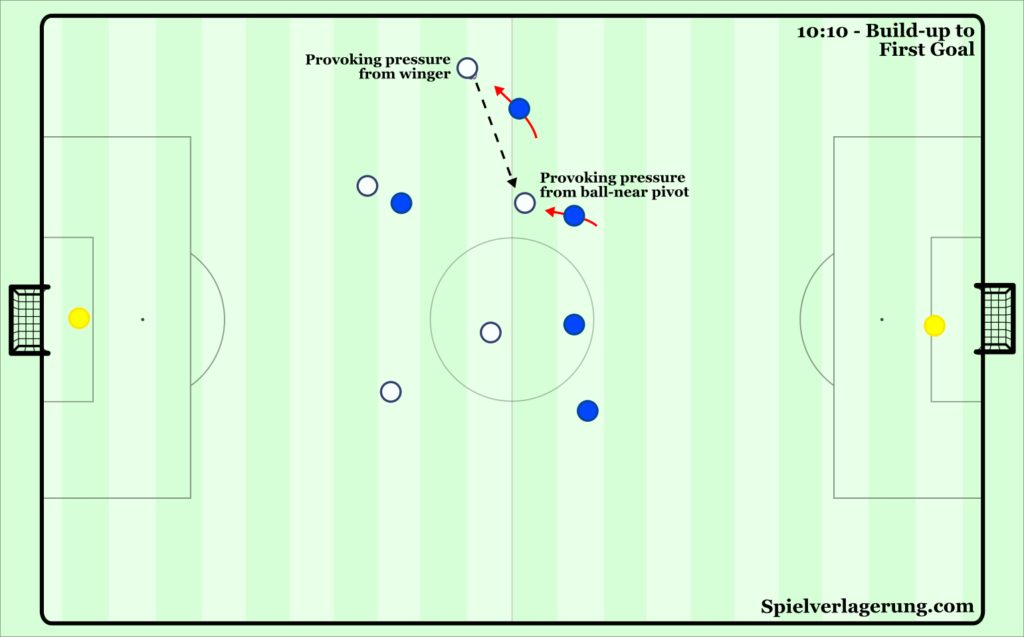

This 3-box-3 structure created an effective solution to progress against Chelsea’s 5-4-1 midfield press. We can break down their strategy between the actions of provoking pressure and pinning, two ways of reducing oppositional cover.

Through Wimmer’s deep position, the Austrian provoked Pedro to move out from the midfield line and press. If Pedro didn’t Chelsea wouldn’t be able to get pressure on the ball. It would be difficult for Costa to consistently press Wimmer along with the two centre-backs in Tottenham’s first line, and he could be bypassed with a bounce pass into the pivot and out to the central centre-back. Dembélé’s position in front of Chelsea’s midfield line offered a safer option for Wimmer to play in but draws Kanté out of position to press him. So, to try and put pressure on Tottenham’s build-up, the two ball-near midfielders had to step up from their line.

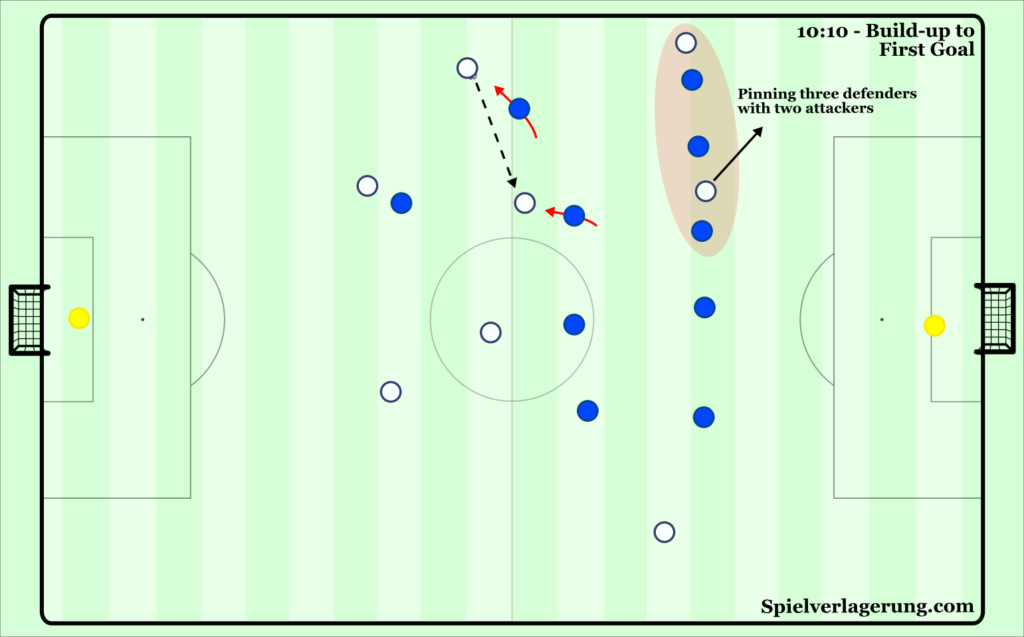

In the last line, Tottenham had three attackers against five defenders, but with the ball-near winger very wide and the centre-forward between the ball-near wide centre-back and the central centre-back. Between the two, they pinned the three defenders who could possibly defend the space behind Pedro and Kanté who have stepped up. Thus, the two forwards consolidated the space between the lines which was initially opened through the build-up players provoking the pressure.

Against a defensive system such as the 5-4-1, where there is only one line of midfield and no covering pivot, these pinning actions from ball-near forwards become particularly important. This is because the defending team’s cover of the space between lines comes from forwards pressure from their defenders as opposed to another midfielder shifting around and screening. To make the comparison, had they been playing against a 4-1-4-1 shape, the position of Eriksen may have been more important from a pinning perspective to stop the defending pivot from shifting over as much to cover the space created.

Aided by Dembélé’s proficiency under pressure, Tottenham were able to play past Pedro and Kanté to find Dele who, along with Eriksen, occupied the space between the lines. Given that Tottenham mainly built-up through their left, Eriksen wasn’t accessible since he mainly occupied ball-far spaces. The Dane was a key factor for follow-up actions though, as he moved inside once the midfield line was broken. He was able to pick the ball up from Dele to score from the edge of the box to open the scoring.

Before Chelsea adapted in the second half, Pochettino’s side created another good chance from this structure in the 32nd minute.

The context was slightly different in build-up, as Wimmer received the ball from Vertonghen wide enough that he couldn’t be pressed from Pedro, so he immediately had space to play forwards diagonally. Chelsea defended this situation differently from the goal, as Azpilicueta stepped up to Dele so the #10 couldn’t receive. Wimmer read the situation well and instead played behind Azpilicueta into Kane who moved beyond. Similarly to the goal, Kane carried the ball forwards and got a shot off from just outside the box, this time saved by Courtois.

It says something that from both situations with good build-up by Tottenham, they still weren’t able to penetrate the Chelsea last line and instead took shots from the edge of the box. A big factor in Chelsea’s approach to high and midfield presses was that if the midfield line was bypassed, they still had a strong back five to defend with. They rarely would concede overloads in these situations with good distances between the defenders, and teams were less capable of converting these dangerous situations into good shooting opportunities.

Inconsistent Creation of this Structure

Despite Tottenham’s success at times with this structure, they let themselves down by not being able to consistently bring all the parts necessary together to create a free player between the lines.

Again, we can quite easily explain this from a theoretical perspective. When a team is in possession, the off-ball players can mainly perform two actions. They either:

- Act as a passing option to receive the ball

- Reduce oppositional cover, enabling teammates to be passing options

The second action can be done in a few ways, but is mainly done through:

- Pinning – where you stop defenders from moving out of their position to cover other spaces

- Luring – where you draw defenders out of their position into other spaces to open the space that they leave.

Side note – luring can also be done by an on-ball player through allowing a defender to approach you, as Wimmer did.

To consistently create spaces to progress into, an attack usually requires off-the-ball players to perform both actions of reducing oppositional cover along with players to act as passing options.

Although Tottenham could reduce oppositional cover through luring both as on-ball and off-ball players, they struggled to consistently have pinning players at the same time as options to pass into.

Dele didn’t always occupy the space in which he received during the build-up to the first goal despite Kane and Son having positions to pin the defenders. This would mean that Kane would have to receive despite being in a position close to Azpilicueta and Luiz, who could defend him quite comfortably. In other situations, Dele was present to receive but without Kane pinning ahead of him, Chelsea’s defenders again could easily step up and defend the situation. As a result, Tottenham struggled to create breakthroughs into space.

Lack of Rest Defence on Right Side

On the right side, most of Tottenham’s attacks came in the form of switches to Kyle Walker’s high position where he could drive at Alonso or into space. Although the away side created two chances from this in the first half, it was the right-back’s positioning which played a significant role in Chelsea’s winning goal early in the second half.

If Kyle Walker moved forward, he was often running the risk of leaving Eden Hazard in space behind him if the ball was lost.

In the build-up to the goal, the full-back sprinted forwards particularly early after Tottenham regained the ball while his teammates in midfield looked to stabilise possession. However, Eriksen and Dembele lost the ball after being pressed by Pedro, Kanté and Matić and the ball ricocheted out to Hazard. Although his compatriot Dembélé recovered, he was able to free Costa down the line who carried the ball before crossing it which Victor Moses finished following a run from deep.

Second Half – Conte’s Change to Increase Pressure

For the second half, Conte made an adaption to their strategy without the ball.

In the first half it was mainly the responsibility of Pedro to press Wimmer, but now Victor Moses became much more aggressive in his positioning and instead pressed the full-back instead. Behind Moses, Chelsea’s defensive line shifted across more so that Azpilicueta directly defended Son while Luiz was on Kane. This more aggressive pressing scheme allowed Chelsea to restrict the effect of Wimmer’s positioning in providing stability, since they had greater access to apply pressure on their opponent’s first line of build-up.

Not only this, but it made an important effect on Pedro’s defensive role too. Instead of having the responsibility of stepping out to Wimmer, he could keep a narrower position and screen passes inside while being available to then step up to Vertonghen. His position to screen inside meant that Kanté could focus more on screening instead. It also allowed Pedro to take on a better position for if Chelsea were to win the ball and transition from, since his base position would mainly be in a pocket between the left-back, left centre-back and pivot.

Ultimately through this change, Conte stopped Tottenham from creating the space that they made in the first half. This was done through increasing their access and thus pressure on the last line while having a more man-to-man approach with their defenders. Although this man-for-man approach in the last line could have led to more space being available for Dele again, the midfielder still failed to occupy the position consistently. Through this man-orientation, Chelsea did however leave themselves more exposed in chaotic situations where lost duels over loose balls could lead to two vs ones, but Dele and Eriksen missed two good chances to equalise. After the second chance, it seemed as though Chelsea became more conscious of this fragility and for the last 20 minutes, they only defended as aggressively if there was clearly sufficient cover behind Moses. Otherwise, they reverted to defending in the 5-4-1 they used in the first half.

Tottenham still failed to consistently occupy the space between Chelsea’s lines. With Dembélé now acting as the attacking midfielder after Dele moved wide, he and Kane seemed to act independently of each other. When one player looked to receive the ball, the other was never in a position to reduce oppositional cover of his space through pinning or luring movements, somewhat similarly to the first half between Kane and Dele. Tottenham only created two other chances in the last 20 minutes. The first from a transitional situation where they switched the ball to N’Koudou in space on their left. Their other chance again came through N’Koudou where he made a direct dribble against Ivanović and then Azpilicueta but ended up shooting from a wide angle.

Final Third

One of the many strengths of Conte’s Chelsea was their ability to defend in a low block. It could be so difficult to break down their defensive line of five with two pivots ahead who were so good at covering space and winning duels. Many teams sought to create from playing on the outside of their 5-4 block and Tottenham were no exception. Pochettino’s team mainly had three ways of attempting to create against Chelsea’s low block.

- Quite often they looked to play deep crosses into Kane from half-space positions either by a deep full-back or a pivot. The striker looked to find positions between the ball-far centre-back and wing-back, either by peeling off onto the blindside of the centre-back or by arriving from wider. Sometimes he would be supported by a decoy movement from Son moving across the centre-back if the cross was from the right. However, none of these crosses connected, in part due to the presence of Chelsea’s five-man defensive line.

- Tottenham had more success by switching the ball quickly out to Kyle Walker for him to run at Marcos Alonso. Christian Eriksen’s positioning for such moments naturally aided his full-back, as he would make it difficult for Gary Cahill to double-up with Alonso while Hazard would never drop into the last line in Chelsea’s defensive system.

- A common result of Chelsea’s defensive stability in the low block is that teams often resorted to shots from distance without the ability to break them down centrally. Tottenham fell victim to this trait too, although I’m not sure how much their goal played an impact on this, since Eriksen scored from outside the block – however it was in a much more open situation. Tottenham’s midfielders missed good opportunities to play the ball out to the full-back when taking these speculative efforts.

Conclusion

Pochettino’s side had some interesting approaches to Chelsea’s 3-4-3 both with and without the ball. Against Tottenham’s high press, Chelsea found some effective solutions to play over the pressure which also reduced the risk of their play. For the away side in possession, they showed an effective approach to breaking through Chelsea’s 5-4-1 midfield press but failed to do so consistently enough over the course of the game. Chelsea also adapted to Tottenham’s threat well for the second half and defended well in a lower block for periods where Tottenham struggled to break them down.

[ad_2]

Source link