Eric the Eel: A Unique Tale of Hope and Struggle … And Lifeguards on Alert

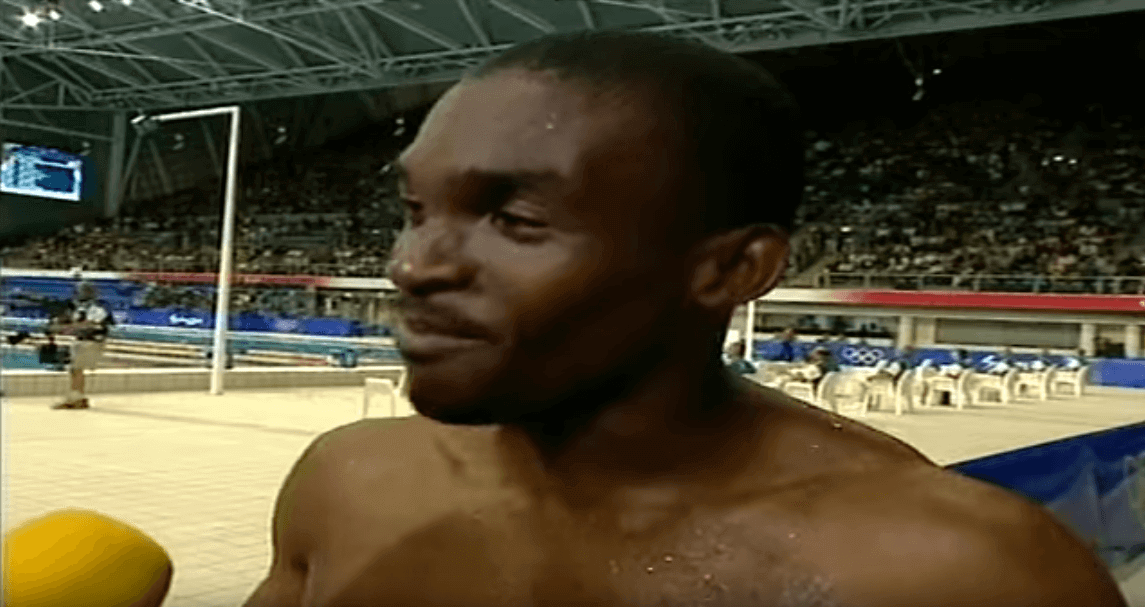

Swimming World takes a look back at the tale of Eric Moussambani, dubbed “Eric the Eel.” The swimmer from Equatorial Guinea barely made it through his 100-meter freestyle, but was a model of perseverance and determination.

Citius. Altius. Fortius. It is the Olympic motto, adopted in the late 19th century by Pierre de Coubertin, considered the founder of the modern Olympic movement. Translated from Greek, the motto stands for: Faster. Higher. Stronger.

From Johnny Weissmuller to Sergey Bubka to Pyrros Dimas, hundreds of athletes through the years have fit de Coubertin’s words, their performances etched in Olympic history. But in the case of Eric Moussambani, who made his lone Olympic appearance at the 2000 Games in Sydney, another motto would have been more appropriate: Slow. Slower. Slowest.

There is no doubting the heart of Moussambani, who was a 22-year-old in Sydney and the first swimmer to represent Equatorial Guinea at the Olympic Games. He trained hard. He carried himself with honor. He put forth his best effort during his one race. But Moussambani was anything but an Olympic-caliber athlete. Instead, he was a token invitation by the International Olympic Committee to generate interest in various sports in developing countries, his homeland located on the western coast of Middle Africa.

The wildcard given to Moussambani to contest the 100-meter freestyle was in stark contrast to the berths awarded to the world’s leading aquatic nations, such as the United States and Australia. In those countries, only the top-two finishers in each event qualify for Olympic action, making their Trials cutthroat in nature. Through the years, the United States’ third-place finisher in some events would have contended for the Olympic podium, but instead was left home.

Moussambani didn’t have to deal with such a dilemma. Then again, he didn’t have to think about racing more than once, since advancing to the semifinal round of the 100 freestyle was never a possibility. Truthfully, the biggest question facing Moussambani was whether he could complete his two laps of the pool at the Sydney Aquatic Centre.

As Moussambani prepared for Sydney, he utilized the facilities and guidance that were at his disposal, which fell far short of Olympic level. While Moussambani conducted most of his training in a hotel pool, which was only 13 meters long, he also spent time in rivers and lakes. More, his coaching came from fishermen, who tried to coordinate Moussambani’s arm and leg movements to prevent sinking. To suggest his preparation was not ideal would be an understatement.

Upon his arrival in Sydney, Moussambani was struck by the sights of a foreign city and the size of the Olympic Village. But nothing overwhelmed Moussambani like the Olympic pool, which was surrounded by seating for 17,500 spectators and would soon ask the novice swimmer to complete an up-and-back trip.

“When I saw the swimming pool for the first time, that was the first time I had seen a 50-meter pool,” Moussambani said. “I was so scared. The pool was so big for me. I wasn’t sure. My training time (before the Games) was at the same time as the United States. I would sit down and see how they trained because I didn’t have any technique. I just sat and watched and tried to learn from them. I didn’t have any experience how to dive and how to start. I had to ask people how to do it.”

When it was time for Moussambani to take the blocks, he was scheduled to compete in the first of 10 heats, and was slated to race alongside Niger’s Karim Bare and Tajikistan’s Farkhod Oripov. Of the three, Moussambani best fit the look of an Olympic swimmer – at least out of the water. He had defined arms and large pectoral muscles, and his abdominal muscles could pass for someone who had trained vigorously.

Standing on the blocks and awaiting the starter’s signal, Moussambani maintained his composure when Bare and Oripov prematurely dove into the water and were disqualified. Shortly thereafter, Moussambani was told he would race alone, information which triggered a look that was a cross between confusion and utter fright.

“I was so nervous,” Moussambani said. “When they called my country, I saw so many people (in the stands) and now I had to swim in front of them. I was so scared the people were going to laugh at me. But something came in my mind that I could do it.”

With Bare and Oripov removed from the deck, Moussambani stepped onto the blocks for a second time and prepared for his solo act. Soon, he was in the water and had the crowd fully behind him. Although he maintained a consistent speed during the opening lap, Moussambani thrashed through the water, his arm and leg movements hardly in sync, and his head out of the water, rather than in a coordinated breathing pattern. Yet, for all his struggles, Moussambani forged on, and even managed to successfully complete a flip turn at the midway point of the race.

But that’s when doubts started to arise, and not just in the mind of this sudden crowd favorite. Between Moussambani, the crowd and the journalists, a simple question surfaced: Was he going to make it to the finish? With every stroke, Moussambani slowed and struggled to stay on top of the water. Simply, he was a sinking ship, albeit one that had plenty of support.

“At the turn, Eric the Eel vanished,” wrote Craig Lord, who created Moussambani’s nickname, in the Times of London. “He was under a long time. A hush descended on the crowd. Eric looked like he was caught in a riptide. Was he facing up or down, and did he know it himself? The sense of relief in the venue was tangible when the man from Molabu surfaced to take a breath. The largely Australian crowd – nearly every man, woman and child probably capable of swimming faster than Moussambani – warmed to the occasion and lifeguards stood by, poised to plunge in for the rescue.”

During his second lap, Moussambani continued to flail and as he neared the end of his epic journey, it looked like he was about to grab onto the lane line, which would have led to his disqualification. It would have been the easy way out. Instead, Moussambani fought through the pain he was sensing and his burning lungs and touched the wall, stopping the clock in 1:52.72. Officially, Moussambani was credited as the winner of Heat One, but his time placed him 71st out of as many finishers.

How slow was Moussambani? The 70th-place finisher, Bahrain’s Dawood Youssef Mohamed Jassim was 50 seconds faster and the last-place finisher in the women’s 100 freestyle was timed in 1:19.12, 33 seconds quicker than Moussambani. Meanwhile, the Netherlands’ Pieter van den Hoogenband claimed the Olympic title in 48.30, more than a minute faster than Moussambani’s effort. In the 200 freestyle, twice the distance at which Moussambani competed, 26 swimmers posted swifter times than Eric the Eel.

A trawl through history places more perspective on the performance of Moussambani. When the 100 freestyle was held at the first Modern Games in Athens, Hungarian Alfed Hajos captured the gold medal. His time? It was more than 30 seconds faster than the numbers that flashed on the scoreboard in the first heat in Sydney.

Still, there was a sense of relief and accomplishment for the African athlete.

“The first 50 meters were OK, but in the second 50 meters I got a bit worried and thought I wasn’t going to make it,” Moussambani said immediately after his race. “Then something happened. I think it was all the people getting behind me. I was really, really proud. It’s still a great feeling for me and I loved when everyone applauded me at the end. I felt like I had won a medal or something.”

Moussambani actually had a female counterpart in Sydney as he was joined on the Equatorial Guinea team by Paula Barila Bolopa. Unlike her countryman, Bolopa only had to swim 50 meters. Like her teammate, she set a record for time futility while having the crowd behind her every stroke.

Bolopa covered her one lap in 1:03.97, which placed her 73rd and last among the athletes who contested the event. The 72nd-place finisher, Guinea’s Aissatou Barry, was timed in 35.79, more than 28 seconds faster. Bolopa, too, was given a nickname before leaving Sydney, as she was tabbed “Paula the Crawler.”

.jpg) Of course, there was no medal draped around Moussambani’s neck. But he was treated as a celebrity for his inspiring swim. He was one of the most popular athletes in the Olympic Village and viewed by some as the definition of the Olympic movement. Although de Coubertin developed the Olympic motto that stressed athletic prowess, he also said, “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning, but taking part. The essential thing in life is not conquering, but fighting well.” The description fit Moussambani perfectly.

Of course, there was no medal draped around Moussambani’s neck. But he was treated as a celebrity for his inspiring swim. He was one of the most popular athletes in the Olympic Village and viewed by some as the definition of the Olympic movement. Although de Coubertin developed the Olympic motto that stressed athletic prowess, he also said, “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning, but taking part. The essential thing in life is not conquering, but fighting well.” The description fit Moussambani perfectly.

Moussambani had the chance to shake hands with Australia’s Michael Klim, his swimming hero. Ian Thorpe, the world’s most popular swimmer at the time, offered his approval, saying, “This is what the Olympics is all about.” Thorpe’s vantage point, though, was not shared by Jacques Rogge, the President of the International Olympic Committee and former Olympian in sailing. Rogge thought the spectacle was a sham.

Speedo, looking to capitalize on his rising popularity, had Moussambani perform promotional work throughout Europe for the next year. Eventually, that partnership ended and Moussambani drifted into the shadows. Having improved by a full minute since Sydney, he had hopes of competing at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. But errors in his accreditation – likely triggered by the Equatorial Guinea government – prevented that opportunity from developing.

Following his competitive days, Moussambani served as the national-team coach for Equatorial Guinea, training athletes a few days each week after fulfilling his regular job as an IT engineer. However, he’ll always be remembered for his role as an athlete, and the heart he exhibited in a single Olympic race.

“The time wasn’t good, but I did it,” Moussambani said, reflecting on his Olympic foray. “The experience of the Olympics is not just about competition. It’s also about participation and the spirit (of doing your best). I think that’s what made me famous. When I got out of the pool, people came up to me and gave me congratulations. When I was walking around the Olympic Village, people were asking for my autograph. It changed everything in my life. People knew my name and my country. It let me try to grow the sport in my country.”