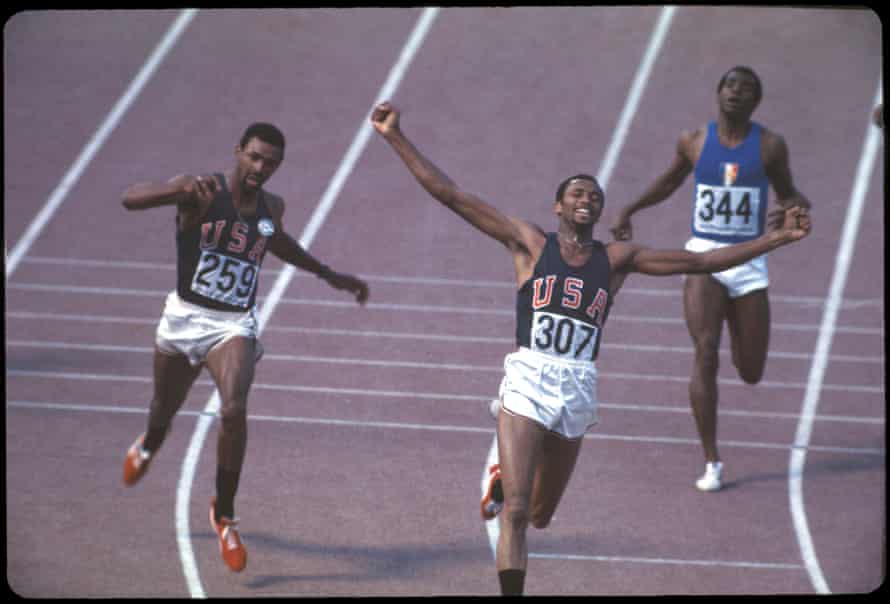

Tommie Smith still gets chills when he hears the opening bars of The Star Spangled Banner. It takes him right back to that night in October 1968 when he stood on the Olympic podium in Mexico City, wearing his gold medal, and made the raised-fist salute that has defined his life. “It’s kind of a push, when I hear ‘dum, da-dum’,” he says, singing the opening notes of the United States national anthem. “Because that’s the first three notes I heard in Mexico, then my head went down, and I saw no more of it until the last note.”

While the anthem played, all that was going through Smith’s head, he says, was “prayer and pain”. Pain because he had picked up a thigh injury that day on the way to winning the 200m final (he still set a world record). And prayer because Smith was not just putting his career on the line – he was risking his life. There was a real possibility that somebody in the stadium might try to shoot him or his team-mate John Carlos, who was making the salute beside him after winning bronze. In the months leading up to the Olympics, he had been receiving death threats. Two weeks before, Mexican police had fired into a crowd of student protesters, killing as many as 300 people. Martin Luther King had been assassinated just six months earlier. So Smith fully expected that the last thing he would hear, halfway through The Star Spangled Banner, would be a gunshot. “So when I hear that ‘dum, da-dum’, I get chills,” he says. “I got chills then when I sang it,” he laughs, holding out his arms to show the hairs standing on end.

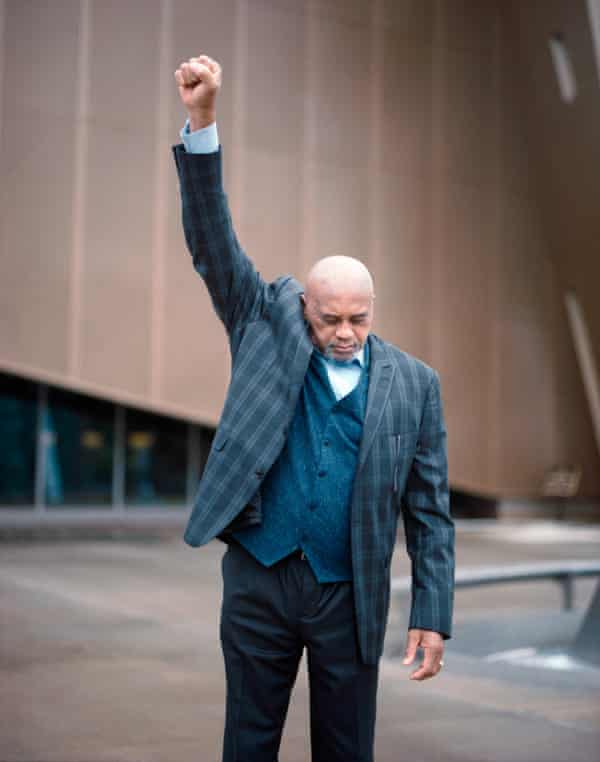

In 1968, Smith seemed like a reluctant spokesman – resolute but nervous in interviews, unaccustomed to being in the spotlight for anything except his running. Today, aged 77, he is relaxed and forthcoming – perhaps as a result of all the public speaking he has done since. The tidy afro has been replaced by a shiny bald head and a grey beard, but Smith looks the picture of health as he speaks from his home outside Las Vegas (he has another home in Atlanta, Georgia). As well as speaking engagements, he works with a leadership academy and has various business interests. “I might be 77, but I’m more active now than I was when I was 50,” he says.

Sports and politics are once more in the eye of the storm, but Smith’s life shows how inseparable the two have always been, especially for a Black man who grew up in the US after the second world war. For Smith, the two were fused together permanently one weekend in March 1965. At an athletics meet on a Saturday, Smith broke his first world records – for the 200m and 220 yards (simultaneously as the track had two finish lines). He then went to join, part-way along, his first civil rights march, a 45-mile walk from San Jose to San Francisco calling for equal educational opportunities. It was a pivotal moment for him. “We were one of the first student marches for a good cause in the history of the United States,” he says. “We were booed by the cars passing. Things were thrown at us. The women and children had to be moved to the middle of the pack, so they wouldn’t be injured.” They arrived in San Francisco, Smith having walked 30 miles, on Sunday evening.

His feet must have been killing him, I say. “You know, back in those days I was used to working because I’m a farm boy,” he replies. “I was kind of tough – physically tough. So it didn’t bother me. I came back, slept overnight four or five hours in my dorm, worked out and went to classes the next day and worked out that evening, and life kept going.”

Smith credits his hard childhood for his athletic ability. In effect, his training began as soon as he could walk, and work. He was the seventh of 14 siblings, two of whom died, in a poor family in rural Texas. As with most Black families in the area, they were sharecroppers – working land owned by white people, who took most of the profits. In the Jim Crow south, Smith barely ever saw any white people, he says, or any other people at all; the nearest neighbours were several miles away. The whole family worked in the cotton fields and lived in a leaky wooden house. When people ask who his favourite athlete is, Smith says his mother. “She had 14 kids and she did the same work as we did in the fields.”

The family moved to California when Smith was six, to better conditions but essentially the same social position. “We were put in a labour camp, to do labour work,” he says. “You could almost call it indentured servitude.” Smith had to work 12-hour shifts every day. “I worked at night, because I went to school during the day,” he says. “We irrigated fields from canals that ran through the San Joaquin valley. So I had to work all night, many times by myself, to make sure the water was going in the right places.” When did he sleep? “You had to sleep when you could. It was very difficult. Easy to get yourself drowned if you fall asleep in the path of water that’s running that fast.”

At high school, Smith’s sporting potential shone through – and in American football and basketball as well as track and field. That earned him a scholarship to San Jose State University, where he studied sociology. As one of the few Black students on campus (almost all of whom were male and athletes), he continued to experience discrimination. “The names I was being called, the way I was looked at, the way I was turned down from renting apartments on college campus and off, and so forth. A lot of so forth.”

In his studies, though, Smith was learning African American history, even as the civil rights movement was writing a new chapter of it. This was the era of the March on Washington; Martin Luther King’s Birmingham protests; the Alabama church bombings, in which four 14-year-old Black girls were killed by the Ku Klux Klan; the assassination of Malcolm X. African Americans were standing up, and being beaten down. Smith felt he needed to act. “I read sociology, but I didn’t do sociology,” he says. “I realised that reading was not good enough. You got to lay that book down and apply to the system what you learned in the book that the system wrote. And a lot of time it wasn’t Black folks that wrote it; it was other cultures that wrote it.”

At the same time, Smith was going from strength to strength on the track: the Usain Bolt of his day. Tall (6ft 4in/1.9 metres), rangy and well trained, he dominated men’s sprinting. In 1968, he held 11 world records concurrently, across 200m and 400m and their imperial counterparts. His 100m time was pretty respectable, too. There was little question he would be on the US Olympics team for Mexico 1968.

The year before, African American athletes had discussed boycotting the Olympics. In October 1967, the activist and academic Harry Edwards formed what became the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), along with Smith, Carlos and the 400m runner Lee Evans (all four were at San Jose State). Soon the hate mail and death threats began.

The goal was human rights, Smith stresses, not Black power. The OPHR had a set of demands: that apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia be excluded; that Muhammad Ali’s world heavyweight boxing title, removed as punishment for his stance against the Vietnam war, be reinstated; that more African American coaches be hired; and that Avery Brundage, chairman of the International Olympic Committee, be removed.

Brundage was steadfastly opposed to politics in sports. He had supported the 1936 Olympics in Nazi Germany, and was doing everything he could to prevent an embarrassing boycott in Mexico. He even sent over Jesse Owens, hero of the 1936 Olympics, to try to talk the Black athletes out of it. Eventually they decided by a democratic vote that each athlete would do as they saw fit. Smith and Carlos were decided on their plan – although, as Smith reminds me, that depended on them actually winning medals. “We were not a group of kids running around and hoping that we win gold medals. We were running around having to win medals to do what we had to do.”

On the podium, the pair’s clothes carried important symbolism. They only had one pair of gloves between them; Smith’s right hand signified “the power within Black America”, he told reporters at the time, while Carlos’s left hand stood for “Black unity”. The black scarf around Smith’s neck stood for Black pride. They wore black socks without shoes to symbolise “Black poverty in racist America”. Carlos’s bead necklace was for the lynchings of Black Americans. In addition, Smith, Carlos and the silver medallist, the Australian Peter Norman, all wore OPHR badges.

Nobody tried to assassinate Smith and Carlos that night, but they still paid a heavy price. Brundage and the US Olympic Committee (USOC) tried to make an example of them. They were expelled from the Olympic village and sent home. When they arrived in San Jose with their wives, nobody met them at the airport except the press. A Black reporter had to give them a lift home.

Most of (white) America regarded them as traitors. “When I came back to California, people shunned me like I was hot lava,” Smith says. “I had a young son and a wife and I had to work, but the only jobs I could find were, like, washing cars. Had I been a white guy who held 11 world records, I believe no matter what I would have done in Mexico City or in the Olympic Games, I would have had some backing.” He was 24 years old, theoretically at the peak of his career, but the USOC banned him from national and international competition. His career was over. During the next two years Smith’s marriage broke up and his mother died – both of which he attributes to the after-effects of Mexico City.

During the 70s, Smith went under the radar. He finished his final year of college, then played football for the Cincinnati Bengals for a couple of seasons, before moving into teaching and athletics coaching, first at Oberlin College, near Cleveland, then in Santa Monica. He did a master’s degree and taught sociology. Over the decades, his moral stand came to be recognised and celebrated. He and Carlos have been inducted into various halls of fame and received numerous awards. The image of Smith and Carlos on the podium is now part of civil rights history – reproduced on T-shirts and posters, recreated in music videos, commemorated in statues and murals, chronicled in documentaries. Smith’s tracksuit and shoes are now on display in the National Museum of African American History in Washington DC.

In 2016, by way of a belated apology, they were invited to be Olympic ambassadors for the US team in Rio. After the games, President Obama honoured them at the White House. “Their powerful silent protest in the 1968 Games was controversial, but it woke folks up and created greater opportunity for those that followed,” he said.

Perhaps Smith’s greatest vindication is that he set a powerful example for other sportspeople to use their platforms. The obvious parallel is Colin Kaepernick, whose decision to kneel during the national anthem in 2016 to highlight police racism caused similar controversy, and fed into the momentous Black Lives Matter movement. Other leading sportspeople have followed suit: Serena Williams, Lewis Hamilton, LeBron James and Naomi Osaka, not to mention England’s national football team.

Smith has not followed England’s Euros saga but has had some contact with Kaepernick, through letters and texts. “We know what happened to us,” he says. “We both used the same platform to do what we felt necessary. He was strong enough to put his feelings on the line by that sacrifice, and doing what he thought he could do.” Like Smith, Kaepernick paid a heavy price in terms of his career, though he has at least received sponsorship and public recognition (a Netflix series based on Kaepernick’s life is coming soon).

As with Brundage in 1968, there are still critics arguing that politics has no place in sport. Rule 50 of the International Olympic Committee’s charter bans any form of “political, religious or racial propaganda”. Priti Patel tried to dismiss the England team’s knee-taking as “gesture politics”, just as Donald Trump and many others characterised Kaepernick’s knee-taking as “unpatriotic” and “disrespecting the flag”.

Unsurprisingly, Smith has little time for that argument. “They thought the flag was more important than the people who worked for it to fly in the first place,” he says. “I have a lot of respect for that flag. Black folks have lost their lives for that flag, just as white folks have. But that was my platform. That’s where the world was looking. I chose the victory stand for my silent gesture. How you viewed it is how you viewed it, because it wasn’t about the flag. I love that flag because it represents my people as well.

“Sports and politics, in my terminology of moving forward and the truth, have always been a part of each other,” Smith continues. “I didn’t wear red, white and blue because they’re my favourite colours. You don’t sing the national anthem because it has a cool beat.” Ultimately, though, Smith was forced to choose between the two. In making one of the world’s most powerful political gestures, Smith sacrificed his sporting career. He wasn’t thinking about his career at the time, though, he says. “I did it because it was for me to do. Whenever God gives you something to do, you don’t question why. You just do it, because the heart says it must be done.”