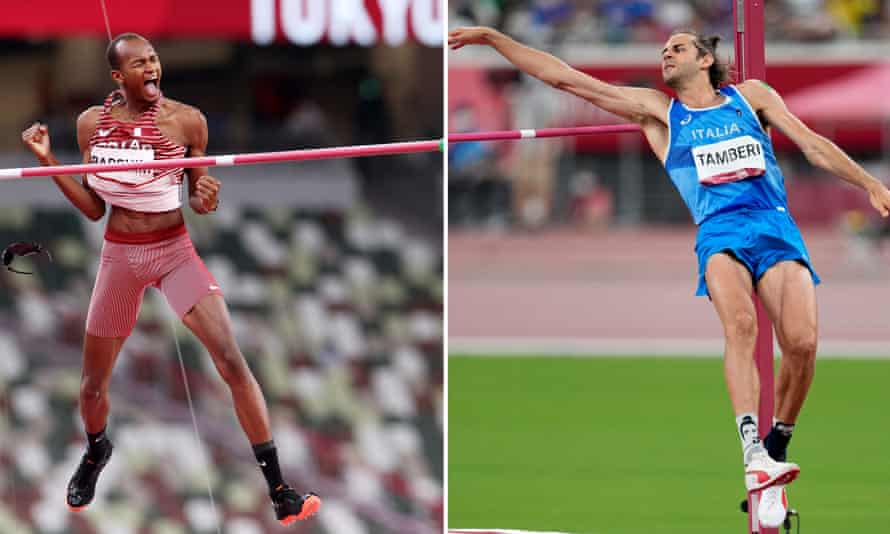

There was a moment, two and a half hours into the greatest men’s high jump competition in Olympic history, where no one had the foggiest idea what was going on. A second earlier, the Italian Gianmarco Tamberi and the Qatari Mutaz Barshim had been calmly talking to an official. Now they were high-fiving, leaping into each other’s arms, and pogoing in pure delirium.

Tamberi then collapsed and began rolling around the track with his hands on his face as if he had been possessed, or shot, or possibly both – while Barshim was using his coach’s shoulder to soak up his tears. It turned out that the most joyous and life-affirming moment of the sporting year was unfolding before our eyes. And soon it wasn’t only Tamberi and Barshim overcome by emotion; the rest of us also found ourselves wiping something from our cheeks.

Until Tokyo there had not been a shared Olympic track and field gold medal since 1912. Yet towards the end of an extraordinary high jump final, in which six men were still jumping at 2.39m, Tamberi and Barshim were still unable to be separated. As the judge began to talk to both men about having a jump off, an idea formed in Barshim’s head. “Can we have two golds?” the Qatari asked, thinking out loud about whether he might be allowed to share triumph with his great friend. “If you want to, you can,” replied the official. There were no more words. Just a look, a smile, then an almighty clap of hands. It was not just an act of sportsmanship. But, in such uncertain times, massage balm for the soul.

However, it was so unexpected that not even Sebastian Coe, the president of World Athletics, knew what was going on. “It was a great competition, everybody was focused on it,” says Coe, who was sitting with IOC vice president John Coates, and the heads of cycling, rowing and gymnastics. “But when suddenly Barshim and Tamberi embraced, everyone started looking at me.” They wanted an explanation as to what had just happened. But Coe didn’t have one. “I was thinking, ‘Guys, what the hell is going on here? Oh my God, they’re going to share the medal,’” Coe tells the Guardian. “And then John said to me, ‘So what’s happening?’

“Well, they’ve obviously come to an arrangement,” Coe replied. Coates’ look said it all. “You’ve let the athletes decide that?”

Eventually Abby Hoffman, a member of World Athletics’ executive board, found a rule allowing shared medals had passed at the 2011 congress in Daegu. “I didn’t remember it at all,” admits Coe. “And I suddenly thought, ‘I bet that went through in a raft of amendments just 15 minutes before lunch’.”

After watching Tamberi and Barshim celebrate, Coe went to bed unsure what the fallout would be. “I thought I’d wake up in the morning to all sorts of negative headlines,” he admits. “But as I tried to sleep I was listening to Radio 4 and they kept saying it was the most uplifting story of the Games and surely worthy of the Fair Play award. By the time the broadcast was over, Barshim and Tamberi were getting a Nobel peace prize.”

There are some who will say that Olympic competition should be about winning and nothing else. But the world of elite sport, which is usually so binary, this was a delightfully non-binary act. And the fact that both men also had shared pain – and rebirth – together only made it resonate deeper.

Tamberi had been one of the favourites for the 2016 Olympics only to rupture the ligaments of his left ankle 20 days before Rio while attempting a personal best of 2.41m in Monaco. It was so serious that he had to be carted off on a stretcher. Many times he feared he would never be as good again. Barshim always reassured him he would. “I didn’t want him to be in the silver medal position,” the Qatari explained afterwards. “Because I knew what he had been through physically and mentally.”

The injury left such a mark that Tamberi even brought the cast he wore after his 2016 ligament surgery with him to the 2020 Games. On it he wrote: ‘My road to Tokyo’.

Incredibly, in 2018, when Barshim suffered exactly the same injury while attempting to break the world record of 2.46m and was out for a year, Tamberi repaid the favour by keeping his spirits up. “I’ve been at his wedding,” explained the Italian. “It’s not just two opponents. It is two friends who can share the best moment of their life together and I think it is magical to have done it. We were good friends before the Olympics. But now it’s like we are blood brothers.”

“I will never regret this choice,” he added. “This year they changed the Olympic motto, Higher, Faster, Stronger, Together. They added this new word, Together, after so many years. We just followed the motto.”

Barshim concurs. He remembers that when he got back to the Olympic village he couldn’t sleep and so he went for a walk. “Literally we were being stopped by every single person we passed,” he says. “The reaction was insane. I love that we did something that touched everybody’s heart.”

That is something Coe, a ruthless competitor in his time, also now acknowledges. “Sometimes those of us in sport are too close, while the outside world has a different perspective,” he says. “And they just thought it was a great piece of humanity. Two athletes from very different backgrounds and very different continents, grasping each other, smiling, and sharing this wonderful moment.”