On June 7, 2018, after 44 years of trying, the Washington Capitals finally lifted the Stanley Cup. In Oakland, California, 43 years, 2 months, and 10 days earlier, the same team took turns lifting a trash can around the ice in mock jubilation.

The achievement they were celebrating? A regular-season road win. It would turn out to be their only one that year.

In every sport, there is always that team – the one that any fan, whether casual or hardcore, can name-drop in casual conversation as a measuring marker for futility. By sheer coincidence, many of these historically awful teams took the field during the mid-1970s, a time of expansion and tumult both in sport and the wider world.

In basketball, the 1972-73 Philadelphia 76ers finished with a historically dreadful 9-73 record. Three years later, the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers lost the first 26 games of their existence, including all 14 in their first season.

Two years earlier, the NHL had their equivalent of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and they played in the nation’s capital.

Birth of the Capitals

In the spring of 1972, the NHL prepared to add two new franchises which would begin play in the 1974-75 NHL season. It just so happened that Washington contractor and businessman Abe Pollin had built a brand new arena in Landover, Maryland – the Capitol Centre. He’d planned to move his Baltimore Bullets NBA franchise inside and was also looking to fill their vacant dates with an NHL franchise.

Sure enough, with the support of 17 U.S. Senators and 42 U.S. Representatives – Pollin and Washington won one of the two slots, the other going to the Kansas City Scouts.

In need of a general manager, Pollin hired Milt Schmidt away from the Boston Bruins, the team he led to two Stanley Cups in the early 1970s. Going from a championship contender to an expansion team is enough of a culture shock at any time, but the circumstances made Schmidt’s job even more daunting.

The mid-1970s was a turbulent era for North American professional hockey, as the NHL had to compete for players with the upstart World Hockey Association. Combined, the two leagues had a grand total of 30 teams, diluting the talent pool in an era when Russian players were off-limits. The two expansion teams were stuck with the scraps that the rest of the NHL didn’t want. The only prospect who seemed to have promise was defenseman Greg Joly, the team’s first-ever draft pick.

As hard as it was for him, Schmidt didn’t help his own case. Inexplicably, the man chosen to coach the Capitals in their inaugural season was Jim Anderson, a friend of Schmidt who had zero coaching experience at the NHL level. He had coached the Bruins’ minor-league affiliate, but that was about it.

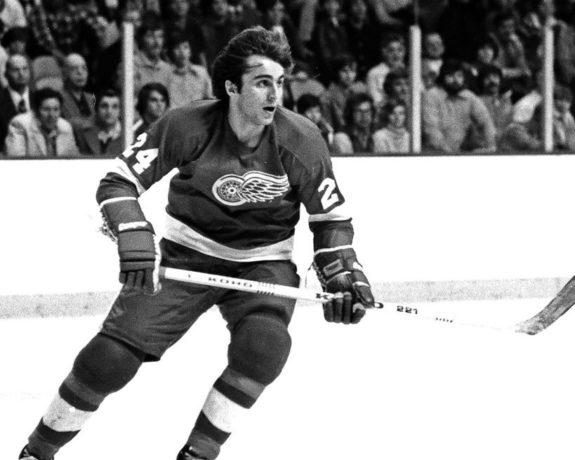

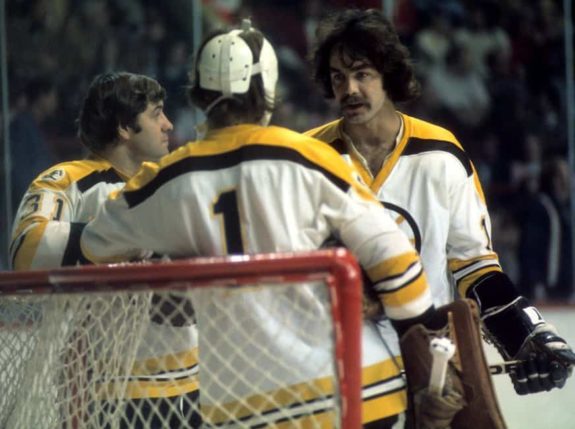

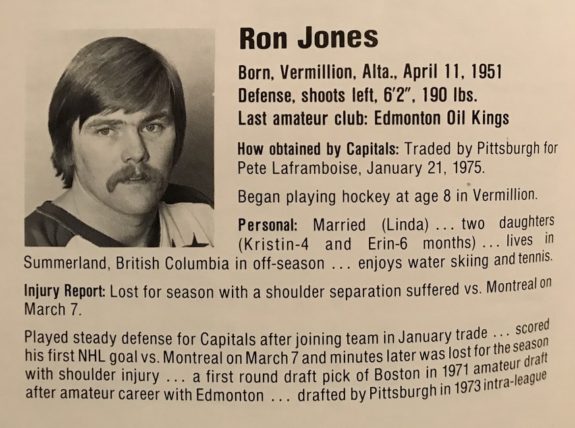

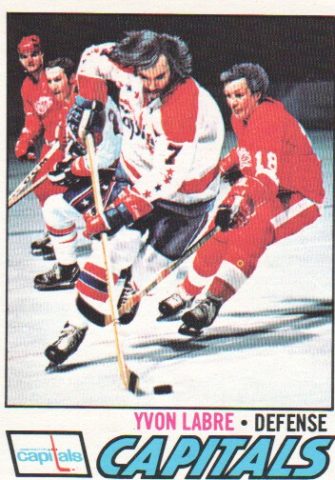

In some ways, the Capitals themselves looked more like the Bruins’ farm team, with all of the baggage they’d picked up from Boston. In addition to Schmidt and Anderson, their roster contained Bruins Stanley Cup holdovers such as goaltender John Adams, defenseman Ron Jones, and forward Garnet “Ace” Bailey.

Expansion Doldrums

Hockey pundits – including those in the local media – expected little of the expansion Capitals. As Sports Illustrated wrote, “The skeptics howled. ‘Won’t win a half dozen games,’ one said. ‘A crime,’ said another. ‘Nixon will certainly desert Washington now. This and Watergate will be too much.’”

Little did they know that the “half-a-dozen” prediction would come dangerously close to true.

At first, Washington came out to support their new hockey team. Over 15,000 packed the Capitol Centre on Oct. 15 for the home opener, a 1-1 tie with the Los Angeles Kings. Two days later came their first win, a 4-3 victory over the Chicago Blackhawks.

The second win wouldn’t come for another 15 games.

By the end of 1974, the Capitals had won only three games, lost 30, and tied four. Even by expansion standards, this team left a lot to be desired. It couldn’t be said that there was nothing left to play for but pride, as even that seemed beyond reach.

Incredibly, this was not as bad as it would get.

A Lousy Season

After that third win of the season, 3-1 over the Toronto Maple Leafs on Dec. 15, the Capitals embarked on another series of prolonged losing streaks. Nine and seven-game skids sandwiched a lone tie with the Boston Bruins on Jan. 7.

With a record of 4-45-5, coach Anderson resigned, as the stress of coaching had left him with stomach ulcers. He reportedly said during the season, “I’d rather find out my wife was cheating on me than keep losing like this. At least I could tell my wife to cut it out.”

After the appointment of interim coach Red Sullivan, two wins in four games in February sparked some hope of a turnaround. That hope evaporated just as quickly, as the Capitals embarked on what is still the longest losing streak in NHL history. From February 18th to March 26th, Washington lost 17 consecutive games, many of them in quite embarrassing fashion. The low point had to come on Mar. 15 when they fell 12-1 to the mediocre Pittsburgh Penguins.

In the midst of the losing, Sullivan lost his job, having never achieved win number three. General manager Schmidt would play double duty for the rest of the season. Since then, only the expansion San Jose Sharks of 1992-93 have matched the Capitals’ record.

The Stanley…Can

Incredibly, as they approached the end of their first season, the Capitals still had not won on the road. By the time they stepped onto the ice for their game against the Golden Seals, all six of their wins had come in the Capitol Centre. And even there, they could hardly rely on the support of their fans, as they had stopped showing up.

Their fortunes had hit rock bottom, and they showed no signs of improving anytime soon.

But fate was with the Capitals that day in Oakland, as they scored twice in the opening five minutes. Late-season pickup Nelson Pyatt scored twice in the final period to seal a 5-3 victory, the Capitals’ first-ever road win and their first win of any kind in 38 days.

In a season with so little to celebrate, the Capitals found their own special way. It just so happened that there was a metal trash can on the visitors’ bench. The accounts of the event vary depending on the source, but one player – possibly Tommy Williams – convinced his teammates to sign their names on the can with a marker.

The team then took turns lifting the can around the ice surface at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum.

“That was our Stanley Cup,” said goaltender Ron Low, according to the Bleacher Report’s retrospective on the season.

End of a Frustrating Season

At the very least, the Capitals managed to end their inaugural season on a high note. In the final game on April 6, they got revenge on the Penguins for their drubbing a month earlier with an 8-4 win, which boosted their record to 8-67-5.

By the end of the season, the Capitals had established multiple long-standing league records for futility. To this day, no team has won fewer games (8), allowed more goals (446), or posted a worse goal differential (minus-265). Some of the players’ stat lines would be unthinkable in today’s NHL. Bill Mikkelson’s minus-82 rating is a record-low that may never be broken. Joly fared little better, with a minus-62, but his career never recovered. Two seasons later, he wound up in Detroit, where he would finish an undistinguished and disappointing NHL career.

Very rarely did these Capitals even keep games close. Over the course of the 80-game season, they lost by an average margin of 3.31 goals, and on four occasions they lost by more than 10. The Capitals’ best-performing goaltender, Michel Belhumeur, posted a goals-against average of 5.36 and went winless in 27 starts.

The rough start had an impact on the growth of hockey in D.C., but thankfully, Pollin had both the money and the resources to absorb the blow, while their fellow expansion team from Kansas City did not. In the 1982-83 season, by which point the former Scouts had relocated twice, the Capitals finally reached the Stanley Cup Playoffs for the first time.

No players remained from the original team.

The archives of THW contain over 40,000 posts on all things hockey. We aim to share with you some of the gems we’ve published over the years.