Black style in the early 2000s was all about going bigger and louder. I wore 5XL tall tees and Girbaud jeans with the straps. They had to match the hat and they had to match the shoes. Red, blue, black? It didn’t matter as long as it all came together head to toe. I also rocked the Sean John velour suits, which had enough fabric to safely land a base jump. I saved up for two years to get a gray one I’d seen on display at a clothing store in Berkeley. I was 6-foot-9, probably weighed 205 pounds, but no one said a thing.

All of which is to say, I was woefully unprepared for the NBA’s newly implemented dress code when I was drafted into the D-League in the fall of 2006.

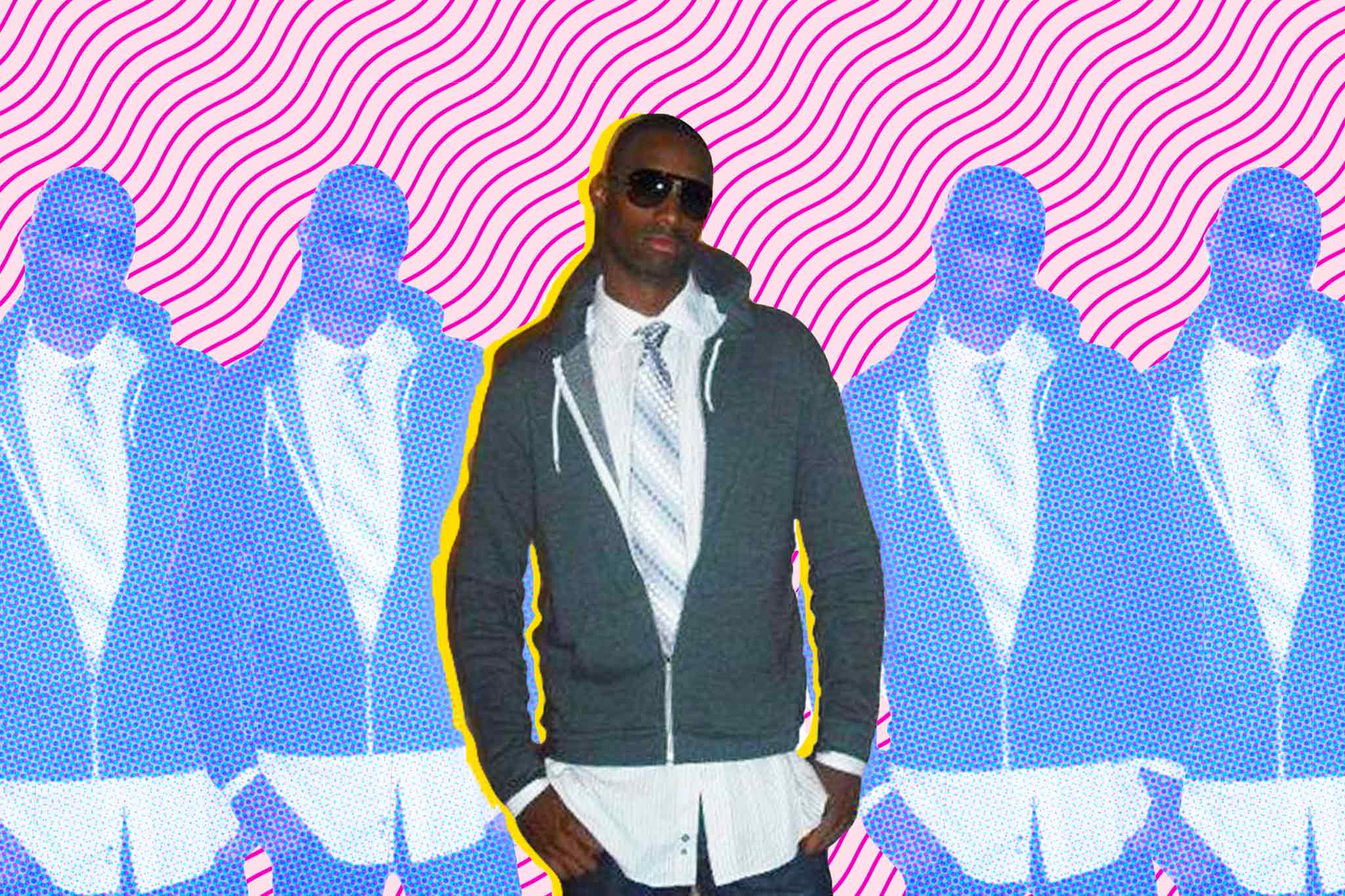

Rod Benson, right, shortly before the 2006 D-League Draft.

Courtesy of Rod BensonFor some context, in 2005 David Stern announced an NBA dress code as a means to “clean up” the league. The announcement was met with enormous, justified backlash from the players and the Black community at large. In America, dress codes have always been racist and sexist at their core. When I was at UC Berkeley, dress codes kept me and other Black and brown people out of certain clubs in San Francisco. Every club had a strict dress shoe rule, so Black people started wearing Steve Maddens because they looked dressy enough but weren’t uncomfortable. Soon enough, the same clubs adopted a “no Steve Maddens” policy. These made-up guidelines were designed to get more specific and restrictive whenever Black people found ways to work with what was considered within the rules — a situation Black folks have dealt with since the beginning of our time in America.

NBA players immediately recognized their new dress code as more of the same. At the very least, these guys had the means to afford new, expensive suits that fit the bill. The rest of us in the NBA’s equivalent of the minor leagues were saddled with the same racist policy and none of the means to afford revamping our whole wardrobe. I remember watching a Warriors game and seeing Ike Diogu on the bench wearing a very large but compliant basic black polo. The stars were starting to dress like the famous people they were, and everyone else was just trying to figure out what to wear.

I soon realized that the code was more so about the outfit itself, rather than the sizing of the outfit. This was important because I was so broke that I couldn’t even afford my own food. My D-League check amounted to $400 every two weeks. I couldn’t buy LeBron James’ tie clip, let alone his entire suited fit. I determined I needed a single black polo and a pair of shoes and I’d be good. Then I ran into another dress code issue: the city of Austin.

At that time, Austin, Texas, was on the come-up. I was happy to be drafted to the Austin Toros. Austin was the location of a recent season of “The Real World.” I definitely had heard about bars like The Dizzy Rooster and the other 6th Street hot spots. Upon arrival, I quickly gleaned that if the NBA dress code was racist, then Austin’s dress code policy was damn near Jim Crow.

I couldn’t get in anywhere with any of the clothes I owned. The only places I could go were the clubs and bars that had mostly Black patrons. I definitely didn’t expect that, because everyone kept telling me that Austin was the “Berkeley of the South.” I think they really underestimated the “South” part of that distinction. The city was very segregated, and I was caught on the side with limited options. So when I went shopping for clothes, I ended up having to fit both dress codes at once so I wouldn’t have to buy double the outfits.

What came out of my bargain bin search for the proper outfit was one pair of Levi’s 501s, one Foot Locker-brand polo, size XL tall, and one pair of the worst-looking shoes Men’s Wearhouse had to offer on my budget of $200. The shoes were brand new and still looked like something you’d find under a freeway overpass. There was a J.B. Smoove stand-up bit about having terrible shoes that look “turned over” and all of my teammates used to reference that when they saw me show up for games.

They could make their jokes about me, but truthfully, all of us in the D-League were trying to look professional, and few of us had the necessary resources. It was incredibly unfair, looking back. Ultimately, we made it work and I eventually got into all the bars. People even forgot about the shoes once I started to play well. The part that never got old was that we all only had one or two game-time fits and more than 50 games to play, so we wore the exact same thing every day. It reminded me of when I was a kid and only had one church outfit, except my grandmother didn’t pick this one out for me and I didn’t match my little brother.

Over the next two years, brands besides Foot Locker started offering tall sizing. My wardrobe grew and the sizes shrunk because, well, I could find stuff that actually fit me for the first time. I wouldn’t say I had “style,” but I definitely was able to dress in code easier and easier. Winter 2006 I was dressed like a sailboat and spring 2008 I looked like an ad for Banana Republic.

Rod Benson and friends at UC Berkeley, circa 2006.

Courtesy of Rod BensonI fully realized the change that was happening in a meeting after practice at training camp with the Indiana Pacers. In the D-League, everyone hated mandatory meetings that didn’t have anything to do with basketball, and in the NBA it appeared to be no different. People weren’t giving their full attention until the woman who was leading the meeting asked, “How many of you guys hate the NBA dress code?”

No one emphatically put their hand up but the clear sentiment was, “Yeah, f—k a suit and tie.”

“Well,” she said, “I’m a stylist and we can add your personal style to these suits. In fact, we can make dress code-compliant clothing that represents you much more than just a gray suit.”

Some guys didn’t care, but others, myself included, perked up at the idea. Mind you, I didn’t have the money to execute, but I took a lot of inspiration that day about what nice clothes could be like in my own life. I imagine that conversation, led by stylists and other fashion-forward folks, was happening in NBA locker rooms across the country.

It accelerated from there. NBA players were finding small ways to take back control of the NBA dress code faster than the NBA could react. Guys were getting crazy interlinings on their suits. All of a sudden came a pair of ripped jeans with a blazer and a Van Halen T-shirt. Can’t get mad at a well-fitted shirt with Eddie Van Halen on it, right? If it was form-fitting, the NBA couldn’t say anything.

From that deduction, new brands formed. Streetwear took on an entirely new meaning. I started my own clothing line around then and went to the Agenda trade show in New York where I witnessed the birth of joggers. I couldn’t believe it. Publish was making pants that were technically khakis but felt like sweatpants and looked dress code compliant. Brands like Supreme, Black Scale, The Hundreds and others were making pants that would have been called “skinny jeans” by every person I knew just two years earlier. The transition was so fast my head was spinning trying to keep up.

Once the generation that was in junior high and high school when the dress code was implemented made its way into the NBA, it was a wrap. Coupled with the burgeoning social media landscape that the NBA was embracing, younger players like Russell Westbrook never felt oppressed by the dress code. It was an opportunity to dress up and be totally unique. I firmly believe a brand like Off-White and its luxury roots could not have blossomed without the NBA dress code. There was no way to stop the players’ wild choices by that point without looking fully racist.

Mostly, the dress code proved again that when faced with policies that don’t align with our values, Black people ALWAYS overcome and innovate. It’s truly a superpower to make lemons out of lemonade over and over again. We showed younger players the blueprint. We not only redefined what the code meant, but we also built a foundation for future generations to harness their individuality.

Russell Westbrook attends the GQ March Cover Party at The Standard Highline on March 1, 2020, in New York.

Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for GQAnd of course, there was one other unintentional benefit to the NBA dress code. I remember going to Las Vegas in 2007, and if you didn’t wear a dress shirt, slacks and shiny black shoes, you might not get into any club. Now you can wear Vans and a T-shirt at almost every place on the strip. It’s a change that has taken hold at every club that wants to be considered “cool.” That obviously doesn’t mean that every bar and club has evolved, but it certainly makes the places with strict and random dress codes look even worse. Yes, I’m looking at you Scottsdale, Arizona, with your dumb “no Jordans” rule, and you, American Junkie in Hermosa Beach, with your “no athletic attire” rule.

So 15 years later, I can still criticize David Stern for his dress code intentions while celebrating what came of it. It’s nice to see that Black ownership of high fashion is at an all-time high. We’re capitalizing on our own style monetarily while also pushing the limits of what high fashion is considered to be. As long as we’re able to challenge cultural and creative norms, who knows? Maybe dress codes will mostly cease to exist someday. I, for one, am all for that.