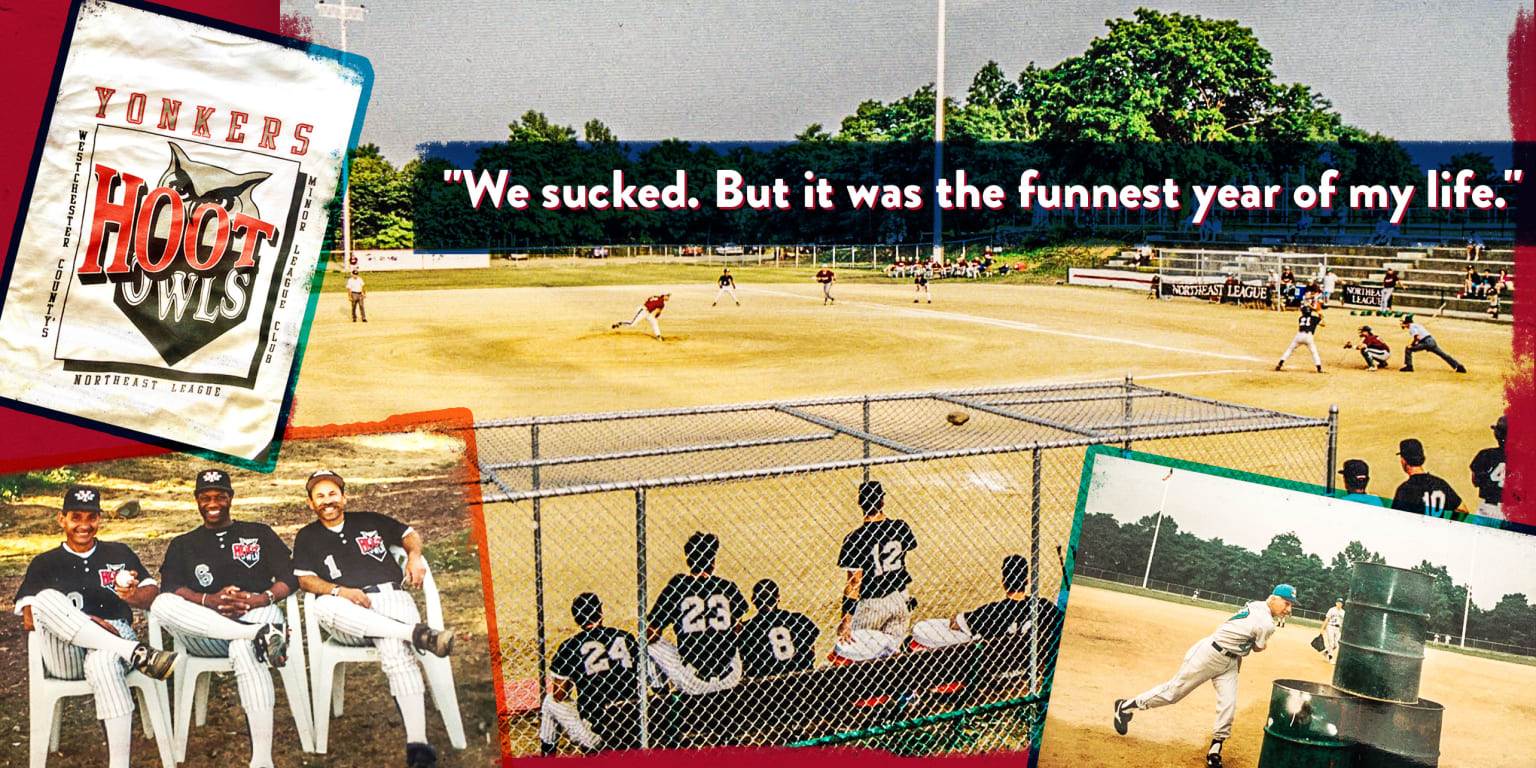

The ballpark has no dugouts. It has no locker rooms. It has no restrooms, no concession stands and no scoreboard. No warning track lines its chain-link outfield fence. No plumbing routes run beneath its all-dirt infield or its spartan slab seats.

Set foot in the facility known as Fleming Field today — in the shadow of the city water tower that blares the word “YONKERS” in bold blue letters — and you would never know it actually housed a professional baseball team in 1995.

Then again, you would not have known it in 1995, either.

Fleming Field was the appropriately abysmal home of possibly the worst team in the history of paid play. They were called the Yonkers Hoot Owls, and their story is a lot like the movie “Major League” … albeit without the uplifting arc or happy ending. In amenities, in attendance and in the independent Northeast League’s standings, the Hoot Owls were dead last, then dead altogether. They lived for just a single, financially ruinous summer.

And yet, while changing into their uniforms in foul territory, mowing their own outfield grass and traveling to road games on a rickety school bus with no air conditioning, the Hoot Owls formed friendships and memories no record can reflect.

“We sucked,” says first baseman Peter Bifone. “But it was the funnest year of my life.”

This is a story about the lengths people will go to pursue their baseball dreams. It’s the story of baseball in Yonkers. And what a hoot it was.

From left to right: Pitching coach Dom Cecere, manager Paul Blair and coach Scott Nathanson.

Independent leagues are where the undrafted, unnoticed or unwanted go to keep their baseball careers alive. They are landing spots for those who either exhausted their opportunity in affiliated Minor League Baseball (MiLB) or never had the opportunity in the first place. The independent Atlantic League has even been legitimized enough to become Major League Baseball’s formal testing ground for various experimental rule changes, and the American Association and the Frontier League have also become official partner leagues with MLB.

But the indy leagues we know today did not yet exist in 1991. That was the year the Professional Baseball Agreement (PBA) that governs relations between MLB and MiLB included a new series of facilities specifications for MiLB clubs. Standards were raised for the seating, playing fields, clubhouses, lighting systems, restrooms, etc. Minor League cities that were either unwilling or unable to perform the necessary updates lost their franchises to cities that would or could.

This development, combined with a strong spectator interest in pro baseball, made conditions ripe for the formation of new leagues — beginning with the Northern League, which was launched in 1993 by former Durham Bulls owner and Baseball America publisher Miles Wolff — that could tap into the country’s thirst for the sport without being bound by the terms of the PBA. And the 1994-95 MLB strike provided added opportunity to get the attention of dissatisfied fans.

Enter the Northeast League.

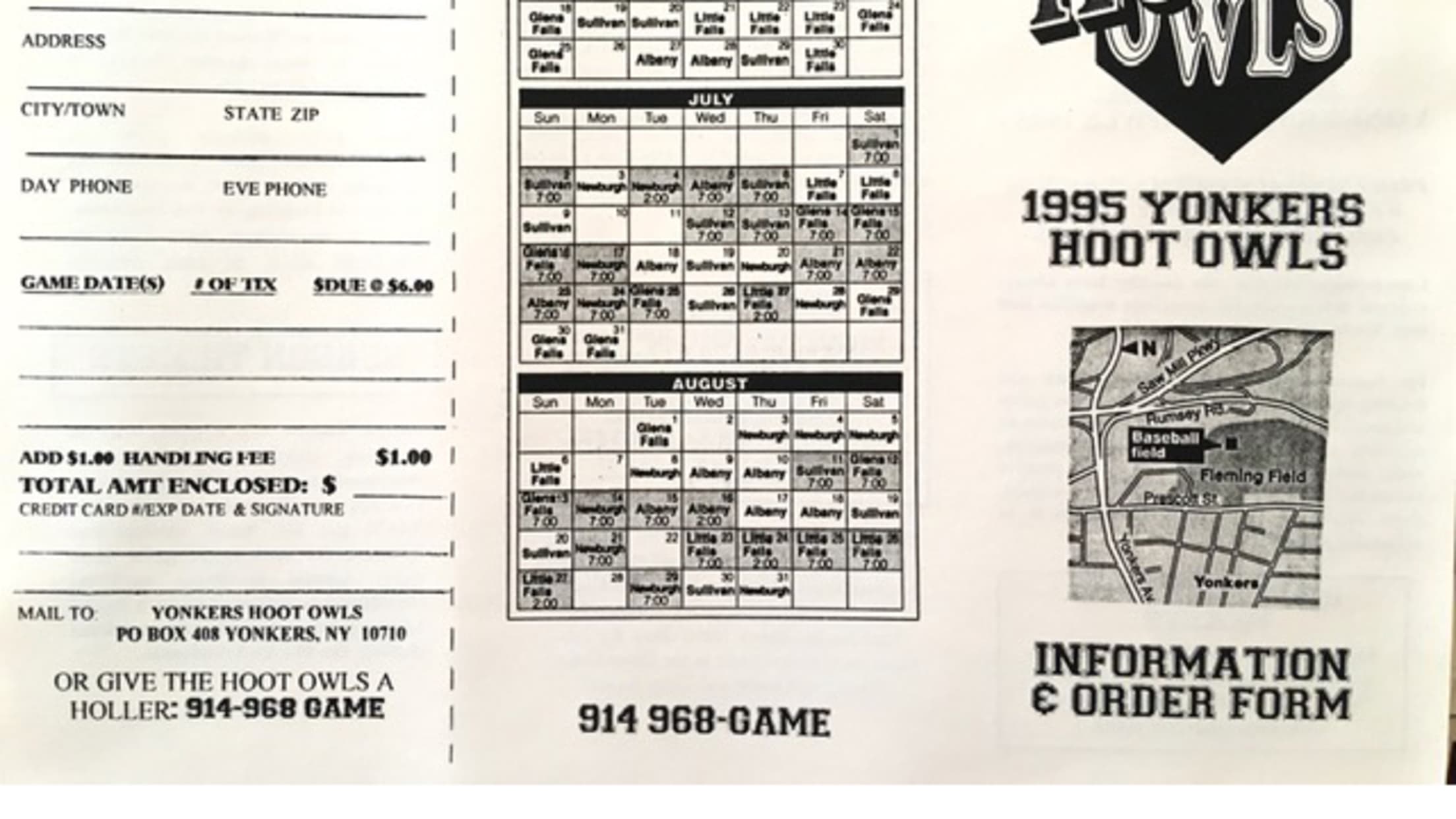

Founded by a book publisher named Jay Acton, the Northeast was envisioned as a six-team league with a 70-game season, at a caliber comparable to Class A ball. All of the initial teams were located in New York state, and the 20-man rosters were mostly made up of college-age players and those cut from the Minor Leagues, with a few former big leaguers sprinkled in.

“We wanted to give the college kids that didn’t make the Draft or were drafted and didn’t make it another chance,” says Larry Massaroni, a former Blue Jays scout who served as the league’s director of player development. “Because it’s hard to get a second chance in baseball.”

Former Mets All-Star outfielder Lee Mazzilli was tapped as the commissioner. Team managers included former Indians skipper Doc Edwards (Albany-Colonie Diamond Dogs) and two members of the 1982 World Series-champion Cardinals — pitcher Dave LaPoint (Adirondack Lumberjacks, based in Glens Falls, N.Y.) and infielder Ken Oberkfell (Sullivan Mountain Lions, in Mountaindale, N.Y.).

Yonkers’ skipper was Paul Blair, the former All-Star outfielder and four-time World Series champion with the Orioles and Yankees.

“Everybody put their real-life experience into it,” Massaroni says. “We all wanted to make it work.”

The league wanted a team in Westchester County, near enough to New York City to garner media coverage. Because it falls within the territorial rights of the Yankees and Mets, Westchester had not had a Minor League team since 1949. But it was fair game to an independent like the Northeast.

Originally, the plan was to place Westchester County’s team in Mount Vernon and to name it the Hoot Owls, with home games at Memorial Field — the building where the famous Coca-Cola commercial featuring “Mean” Joe Greene was filmed.

Then a problem arose: Memorial Field, which had been built in 1930, was condemned by the city.

We sucked,” says first baseman Peter Bifone. “But it was the funnest year of my life.

The focus shifted to Massaroni’s hometown of Yonkers, where he had political connections. There was excitement about bringing pro baseball back to New York’s fourth-most populous city, which had not housed such a team since a Hudson River League club in 1907. Adele Leone, a literary agent and associate of Acton’s, paid the $50,000 franchise fee to own the Yonkers club and wanted to name it the Blue Bandits. But some Yonkers City Council members, leery of the negative connotation of “bandits,” shot that idea down. So against her wishes, Leone’s team took on the nickname of the aborted Mount Vernon team.

The Yonkers Hoot Owls were born.

And quite the habitat awaited them.

Field of Nightmares

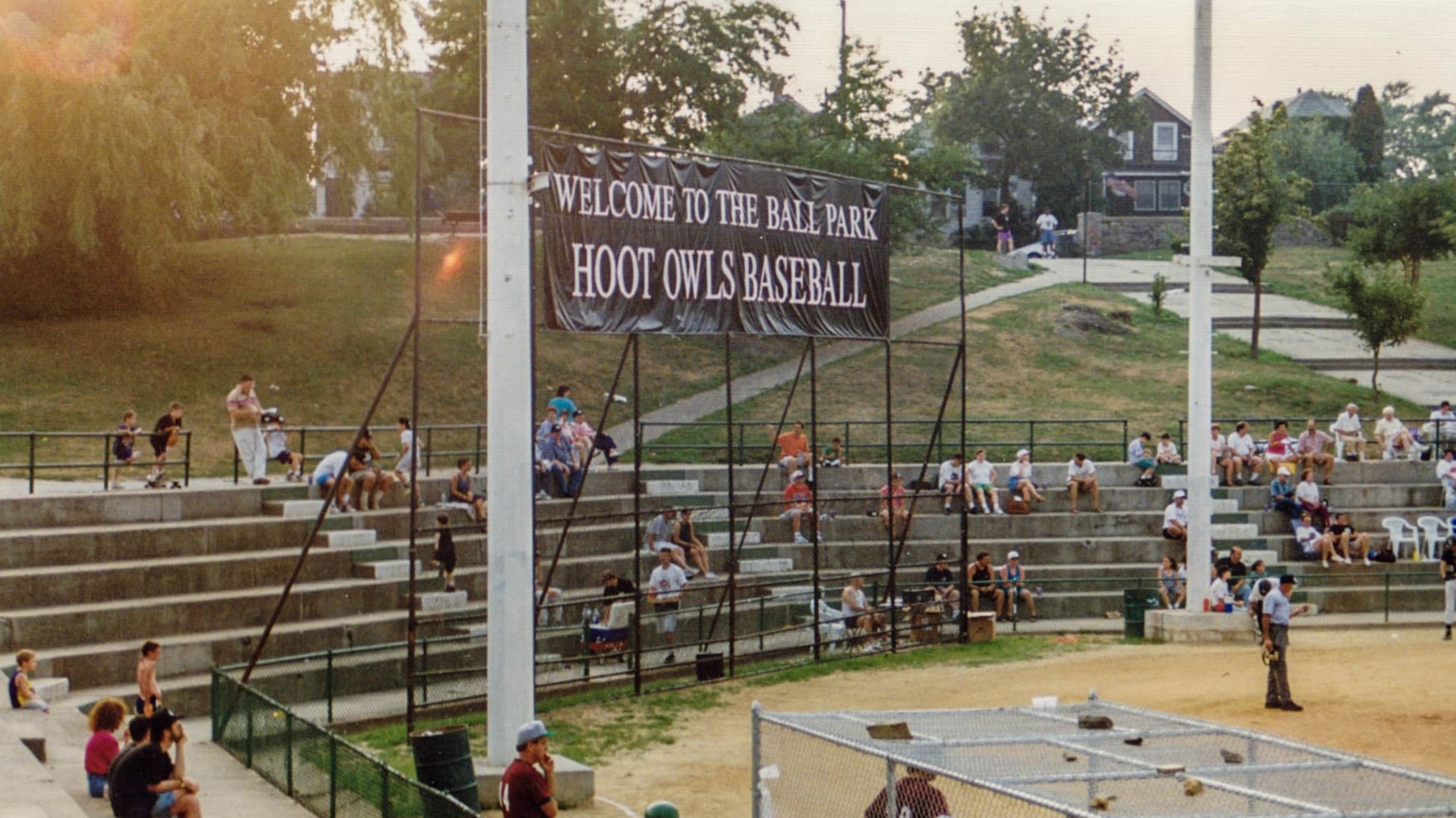

Fleming Field sits just eight miles north of Yankee Stadium, and no one would confuse the two. But with neither the funds nor the time to build a new facility, Yonkers didn’t have much else to offer the Northeast League.

“It had the all-dirt infield and no water,” Massaroni says. “There were a lot of restrictions to it. But it was a good ballpark in that you could seat a lot of people [with a capacity north of 1,000].”

Yonkers general manager Randye Ringler had the tall task of making Fleming Field palatable for professional baseball. An innocent victim of MLB’s work stoppage, Ringler had been laid off from her position as the Mets’ director of marketing a few months earlier. And prior to her 15 years with the Mets, she had been the assistant GM of Class A Charleston and the sales and promotions director for Double-A Memphis. So she had plenty of experience to draw from and contacts to utilize.

She’d need all the help she could get.

“Everything was done on the fly,” she says. “It was not the way you want to run a team. But if you didn’t have to worry about money or having a future career, it was quite the experience.”

Fortunately, Leone sprung for lights, resolving one issue.

Mostly.

“The lights were so low,” Bifone says. “If they hit a pop fly, you couldn’t see the ball. Thank God for the infield fly rule.”

The lack of plumbing created the need for portable toilets and some assistance on the maintenance front.

“My family were all firemen and policemen,” Massaroni says. “So my cousin Hank provided water from the hydrants to wet down the field.”

Folks in neighboring houses let the Hoot Owls use their spouts to fill up water coolers, which came in handy.

“That was a hot summer, and there was no shade,” Bifone says. “After BP, we’d be drenched. So we’re pouring the coolers on each other while changing before the game.”

With no locker rooms and no fan barriers, changing was awkward.

“You’d try to have a friend stand in front of you,” says infielder Brian Moeglin, “so you could put your sliding shorts and jock strap on.”

… if you didn’t have to worry about money or having a future career, it was quite the experience.

It was much the same with the dugout, which was not dug but was very much out. All that separated the players from the fans was a chain-link fence. The Owls were caged.

“The positive spin on it,” says coach Scott Nathanson, “was that you get to see the players in the dugout during the game! It was marketing, you see.”

With no scoreboard, Ringler set up a dry-erase whiteboard on the outfield fence, “operated” by an intern. And because the ballpark wasn’t located in the safest of neighborhoods, the whiteboard and all other signage had to be taken down after every game and hung back up the next day.

“They went through a lot of strip ties that summer,” says LaPoint, the Adirondack skipper.

Adirondack played in Glens Falls’ East Field, which had housed the White Sox Double-A affiliate in the early 1980s. It was a more typical indy league venue with locker rooms, a press box, a scoreboard and wraparound seating for up to 6,000 fans.

So when the Lumberjacks arrived at Fleming Field for their first visit, they were stunned. As if the field conditions weren’t unusual enough, the Hoot Owls didn’t even have the “L-screen” that batting-practice pitchers stand behind to protect themselves. While awaiting the delivery of a screen, the make-do solution was to stack one steel garbage can on top of two others.

“I told my guys, ‘Boys, we won’t be taking BP here,’” LaPoint says. “I’m 6-foot-3, and each drum was 3-foot tall. Those extra three inches are not where I want to get hit by a baseball.”

With no groundskeeper, players tended to the outfield grass themselves, borrowing lawnmowers from their newfound friends in the neighborhood or from family members in the area. And while the all-dirt infield was not unique to Fleming Field (Japan’s Koshien Stadium, used by the Hanshin Tigers of Nippon Professional Baseball, has the same), the Hoot Owls didn’t have the proper equipment to rake it.

“We had some rough hops,” third baseman/outfielder Drew Jemison says. “Lots of rocks.”

To (literally) smooth things over, Ringler bought materials from a nearby Home Depot to make her own infield drag mat. And before, during and after games, she was often the one tending to the infield in her Easy Spirit pumps.

How did she keep her sanity?

“Who says I did?” she jokes.

The Bad News Owls

OK, so the setup was terrible. What about the baseball?

Well, not much better, unfortunately.

While the Hoot Owls managed to make many of their games competitive, they had trouble holding late leads and, perhaps as a product of their frustrating field, avoiding injury.

Their roster was largely comprised of locals. Guys like Jemison, who hailed from across the Hudson River in Nyack and didn’t get drafted out of Mercy College.

“I had done a [Northeast League] tryout in the winter, and then, right before the season starts, I get a call that I made a team,” he says. “We had maybe a week to go through practices. It was a ridiculous contract, like $700 a month.”

Ringler remembers some players making less than that — closer to $500 per month. A few were signed straight out of a tryout camp held shortly before the start of the season. The roster was raw.

(Multiple online sources list one-time Reds outfielder Leo Garcia, a native of the Dominican Republic, as a member of the Hoot Owls. But it’s the wrong Leo Garcia. The Leo Garcia on Yonkers was from Tarrytown, N.Y.)

“I don’t want to say ‘rag-tag,’ because we weren’t rag-tag,” Nathanson says. “But we didn’t have the money to pay our guys what the Albany team or the [eventual league champion] Lumberjacks had.”

One of the few members of the Hoot Owls with previous professional experience was Bifone. He had signed with the Padres as an undrafted free agent out of Bellarmine University in 1993, only to lose his spot in A-ball to first-round pick and eventual All-Star Derrek Lee. When Bifone heard about the Northeast League, he drove across the country, had a tryout and signed on the spot. He spent the next month working the phones, trying to sell tickets and sponsorships in advance of the opener.

“I’m calling all these local businesses,” he recalls with a laugh. “‘Hey, this is Pete Bifone! We’re playing baseball in Yonkers! Wanna buy a banner? What do you wanna pay? A hundred bucks? Deal!’”

Because Fleming Field was not yet ready (and in truth, would never be ready), the Hoot Owls spent the first two weeks of the season on the road. Things started out well. On Opening Day at Adirondack, Yonkers scored some early runs and right-hander Mike Maerten threw a complete game in a 5-3 victory.

That night, as fireworks hailed over Glens Falls in a postgame celebration of the launch of the Northeast League, a teammate turned to Bifone and remarked how awesome the experience had been.

“Brother, don’t get used to it,” Bifone responded. “I don’t think this is going to happen very often.”

He was right. Though the Hoot Owls won a handful of games in the season’s first month, reality caught up with them. They lost 15 in a row at one point.

“To be honest, the Hoot Owls could have won a lot of games,” Massaroni says. “They just had no bullpen.”

Photo via BallparkBrothers.com

The vast experience Blair brought to the ballclub only went so far. Especially with Blair missing the season’s opening series because of prior commitments, missing seven games because of a suspension for shoving an umpire and missing several other games because he was named the general manager of New Orleans’ entry in the United League Baseball (a planned “third Major League” that folded before a single game was played).

But Blair, who passed away in 2013, was around enough to impart wisdom and provide context.

“I was sitting next to him one game, and he started calling out each pitch before it came through, just from watching the pitcher,” Moeglin recalls. “I said, ‘How are you doing that?’ He said, ‘That’s the difference between where I played and where you’re playing.’”

The roster constantly evolved. The Hoot Owls had a new right fielder just about every homestand. When a player was released after a game, he would hand over his uniform (Yonkers had only one uni, used for both home and away games) so that his replacement could wear it the next game. Players routinely fought through injuries out of fear of getting released or benched.

Those who managed to stick around formed friendships, some of which have lasted a quarter-century. They’d blow their paychecks at the Original Crab Shanty on City Island in the Bronx. They’d crash at the apartments of their teammates’ girlfriends so that they could sleep in air conditioning. And because they were the Hoot Owls (and more accurately, because this was the summer of 1995), they’d sing along to the song that became their unofficial anthem — Hootie and the Blowfish’s “Only Wanna Be with You” — and alter the lyrics to reflect their record.

“We’re only 6-22!”

For Love of the Game

Let the record show that the record is wrong.

Several online information portals — from the ordinarily reliable Baseball Reference to the not-as-reliable Wikipedia — peg the Hoot Owls to a final record of 12-52. But a search of newspaper records from that period reveal this to be a gross mischaracterization of their might.

They were actually 14-54.

Alas, even after this uptick in the win column, Yonkers is still left with an unsightly .206 winning percentage. It’s not the worst in history. A search of Baseball Reference’s database found 31 professional teams since 1900 (none from the Majors) who played at least 50 games and had a lower percentage. But the combination of faultiness with the field and futility on it certainly puts the Hoot Owls in some rare, rank air.

“I hate the fact that we might be remembered as one of the worst teams ever,” Moeglin says. “That saddens me. Because as far as the people are concerned, it was one of the best teams ever.”

They did go out on a heroic note, beating the Newburgh Night Hawks, 11-7, in the Aug. 31 season finale at Fleming Field by only giving up four runs in the bottom of the ninth. But by that point, it had become a foregone conclusion that the team would not be back for a second year.

Despite the Hoot Owls’ effort to draw fans from all over Westchester County (their cap logo was a Y over a W, for “Yonkers of Westchester”), their very few wins had very few witnesses.

Northeast League teams went into ’95 hoping to draw an average of at least 1,000 fans per game in order to be financially operable. Yonkers drew about 170 per game. (It didn’t help that attending a game at Fleming Field required parking two and a half miles away and shuttling over.)

The insolvent situation got to the point where team owner Leone and league founder Acton, who comingled their funds, began dismantling the Hoot Owls before the season even ended. Acton showed up one day and fired most of Ringler’s staff. Bifone, one of Yonkers’ best players, was traded to the Sullivan team owned by Acton for three relief pitchers released by the Hoot Owls within days.

“We were so close-knit,” Bifone says, “that guys [on Yonkers] were threatening to walk off the field to protest the trade.”

Amid rumblings of Yonkers employees and contractors not being paid properly, John Purcell of the Glens Falls Post-Star caught up with Leone late in the season to address the financial concerns.

“Green [money] takes care of everything,” she told him. “That’s all I have to say, now run along.”

But just a few weeks later, Leone, who passed away in 1999, admitted to The New York Times that her financial losses from the Yonkers investment were “considerable.”

Are we really this snakebit?

“Initially, bills had been paid,” Ringler says. “Only in the last couple months did we realize the money had run out. The team was supposed to be sold to make everyone whole, but the league played games with us.”

The Hoot Owls were declared dormant. They were effectively replaced in the Northeast League in 1996 by the Bangor (Maine) Blue Ox, who went a respectable 46-33 with the help of none other than Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd. But the balance sheet did not transfer to the Bangor ownership. Any outstanding debts in Yonkers were allegedly ignored.

Nobody got burned as badly as Ringler. She had routinely put in 14-hour days for the Hoot Owls. She ran every aspect of the organization, from designing the team logo to ordering equipment to raking the field and faxing results to the league office after games. Ringler says she accrued about $20,000 of team-related credit-card bills that went unpaid.

“When you’re dealing with independent teams [at that time],” she says, “there’s no governing body. You have nobody to appeal to.”

Though four of the six teams from the Northeast League’s inaugural year either relocated or folded, the league survived three more seasons. It then merged with the Northern League for four years and returned for the 2003 and ’04 seasons before getting absorbed by the Can-Am Association, which is now merged with the Frontier League.

So the DNA of the Northeast League still exists, marking a somewhat successful run.

The Hoot Owls, though, were unsuccessful in every respect, and professional baseball has not returned to Yonkers — or anywhere in Westchester County — since.

(Well, except for a 2011 Can-Am team that was technically based at Westchester Community College but played every game on the road. They were called the New York Federals, and, not unlike the Washington Generals who perennially oppose and lose to the Harlem Globetrotters, they existed only to give the league an even number of teams and to develop players for the other clubs to pilfer. The Federals used 82 players in 93 games and went 15-78. But that’s another story …)

Still, while the Hoot Owls teach us so much about how not to build a baseball team, their members were a refreshingly pure example of devotion to the sport and to each other. In 1996, seven core Yonkers players, along with Nathanson, played together under Oberkfell on a new Northeast team, the Elmira Pioneers.

“It was the same league,” Bifone says, “but a beautiful facility and host families and the way it should be run.”

The stories from Yonkers, however, are what endure for Bifone (a college and high school umpire), Moeglin (a vice president in marketing), Jemison (owner of an embroidery business), Nathanson (managing in the independent Empire League), Ringler (who went on to hold various roles in horse racing, arena football, tennis and sports marketing) and others.

And there’s one story that best gets to the heart of the Hoot Owls’ experience.

The goal of the Yonkers players — the reason they embraced their outrageous arrangement and the nightly comedy of errors — was to reach the highest level their talent would allow. So in an effort to get her players the exposure they needed, Ringler called in a favor from a friend.

That friend was Joe McIlvaine, a longtime scout and executive who, at that time, was the general manager of the Mets. His words carried weight with scouts in the area. With McIlvaine’s assistance, Ringler was able to arrange a midseason showcase, of sorts. A date was circled on the Hoot Owls’ home schedule. As usual, there would not be many bodies in the stands that night, but this time the small audience would include a handful of big league evaluators, people whose recommendations could change a player’s course.

It was all set up. One shot. Catch a break on this night, and all the oddities endured by the Hoot Owls would have been well worth the while.

But that, of course, was the night a lightning storm hit Fleming Field.

Photo via BallparkBrothers.com

With the game called off, with the scouts scattered, with the players having returned to their humble homes, Ringler sat in the trailer that served as her office and had what was a recurring thought in that summer of ’95.

“Are we really this snakebit?”

The answer, obviously, was yes. And that tragicomic twist worthy of Neil Simon himself perfectly epitomized a baseball team that was lost in Yonkers.