JUPITER, Fla. — March is Women’s History Month, and what better evidence of breaking barriers than showing up in elementary school homework? That was the recent case for Marlins general manager Kim Ng, whose friend’s 8-year-old daughter ran to her parents after recognizing “Ms. Kim” in a math pamphlet.

“That’s when you realize just what a big impact that I’ve been able to have, and again, it’s not really about me,” Ng said during a Zoom call. “I think it’s about all the women that came before me and all the women that hopefully come behind [me]. But it really has had a profound effect on me, as well as others, I think.”

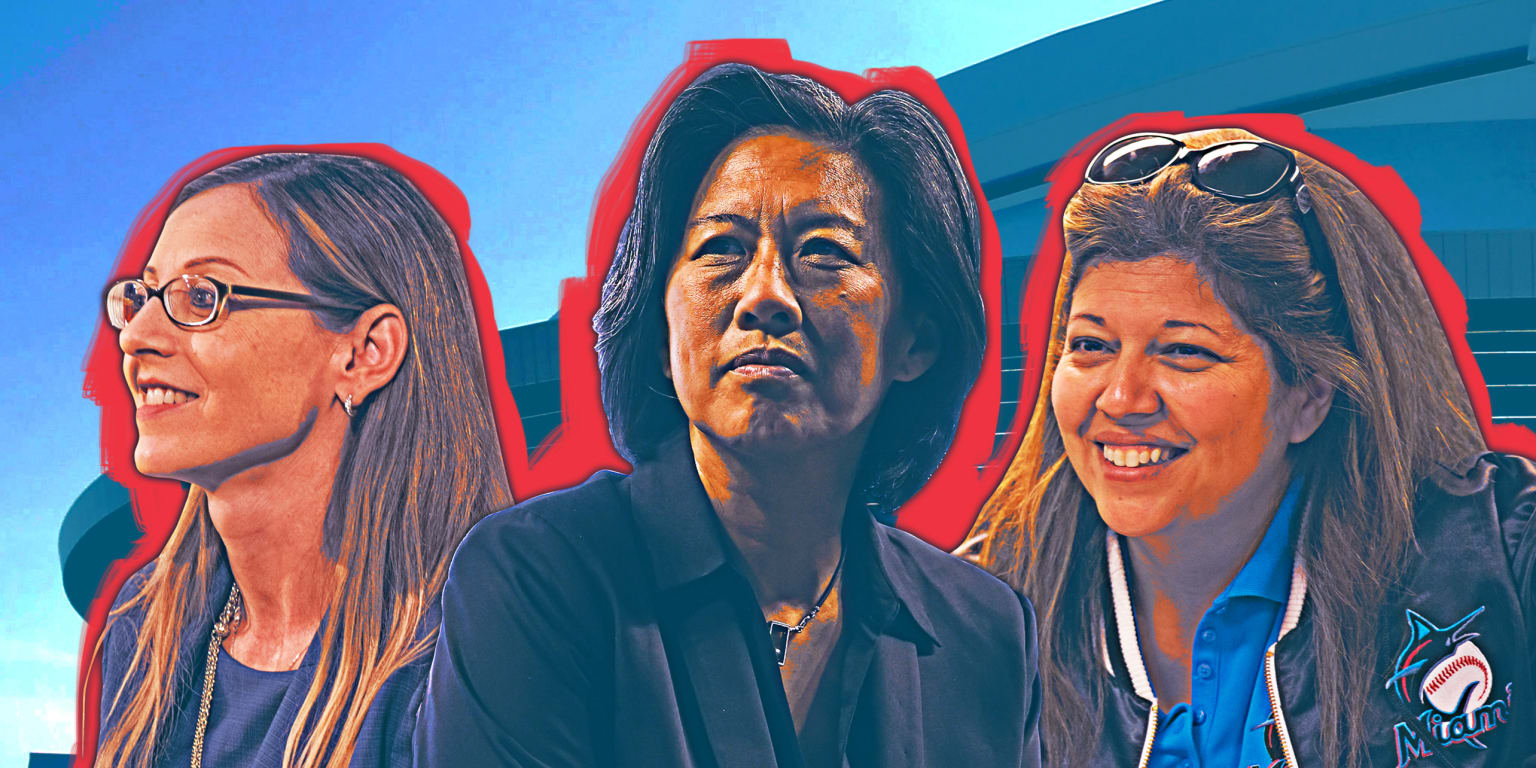

Ng’s hiring in November should come as no surprise. The Marlins have made diversity a priority since the ownership group led by Bruce Sherman and Derek Jeter took over in October 2017. If you go through the front-office directory, two of the five names in executive management are women — Ng and Caroline O’Connor, the club’s chief operating officer.

According to O’Connor, with so many great ideas and conversations about diversity and social issues within the organization, there was a need to funnel them to a central point. So the Marlins came up with the idea of a vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion. They needed to look no further than Raquel “Rocky” Egusquiza, who was already the executive director of the Miami Marlins Foundation. Since taking on this additional role in January, she works alongside Beth Elletson, vice president of human resources and chief people officer, to design and implement strategies that attract, engage, retain and develop the workforce. It is part of the organization’s commitment to the tenets of people, culture and community — both internally and externally with its vendors and partners.

“I understand people say it’s historic, and I didn’t make a decision to be historic,” Jeter told MLB.com. “I’m a firm believer you put the best people in the position to do the job. [Kim] was the best person for the job. Caroline, Rocky, the same thing.”

PEOPLE

While Ng has spent her entire life in the sports realm, the same could not be said for Egusquiza (nonprofit, media, etc.) or O’Connor (banking). Neither imagined a career in baseball, but they now hope to entice a range of prospective employees with the appeal of working in sports. That’s the start of the challenge: Understanding the thought process of someone selecting a career or making a change.

Through partnerships with local colleges and universities, the Marlins have developed early pipeline programs. The organization reaches out to educate the community about opportunities in the sports arena, as well as how welcoming they can be to diverse candidates.

“When you look at the core skills that you have in a sports management degree, it’s accounting, it’s marketing, it’s a lot of the things that you have with other companies,” said O’Connor, who previously worked in another male-dominated field of finance. “It’s just kind of a different product specialty that you get in sports. Those foundational skills like accounting, people management and HR are a lot of the things that other companies are doing, or what translates over here. There’s a lot you have to learn about how a baseball organization works and rules around it, the different programs that we run and different interactions with our different staffs, but a lot of it was transferrable.”

That outreach hasn’t gone unnoticed. Dr. Susan Mullane, associate professor and director of the undergraduate sport administration program at the University of Miami, credits the Marlins for being proactive rather than waiting for mandates to make change. It’s a way to avoid homologous reproduction, when those in power maintain their influence by allowing only those who have similar characteristics to gain access to positions of power and influence within an organization.

Paul Resnick, the sport administration internship director and a senior lecturer at Miami, shares with his students the various diversity and inclusion programs that teams and leagues offer. Resnick, who spent five of six years with the then-Florida Marlins working in community affairs, sees the action as more than just lip service. These initiatives are designed to help more minorities reach their goals and work their way up within the industry. A local team like the Marlins can set an example of positive change that ideally would happen on a global scale. The way Jeter sees it, it’s simply the right thing to do: “If you’re in a position where you can give someone an opportunity, then you should do it.”

“Adding a diverse group like that to a front office speaks volumes to the rest of the sports world,” Resnick wrote in a message. “We’ve been hearing for a long time that front offices needed to be more diverse, and now we are finally seeing it. It makes sense for the Marlins to be a club willing to make this kind of statement. Miami is a diverse city. It’s one of the main things that I love about living and working here — to be immersed in so much cultural diversity is a blessing. It’s an amazing environment to raise my children. They are able to see and interact with people from all walks of life. No doubt, if more people were exposed to a society like we have down here, I’d imagine a world less divided. Happy to see the Marlins have some amazing, highly qualified individuals in decision-making positions.”

According to The U.S. Census Bureau data estimates from July 2019, 69.4% of the Miami-Dade County population (around 2.7 million) is Hispanic or Latino, which is defined as a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race. The rest of the country is at 18.5%. When it comes to race, 12.9% of the county’s population is only white (60.1% for the U.S.) and 17.7% is Black or African American (13.4 percent in the U.S.).

The uniqueness of Miami-Dade County’s demographics presents the chance to capitalize on the benefits of not only the talent pool, but also the diversity it contains. Egusquiza, whose family moved to Miami when she was 4 years old, considers it even more special to create programs that give back to her hometown.

“It’s absolutely important that we reflect the community where we live and work,” Egusquiza said. “We’re the community’s team, and that includes being reflective of that community. There’s research that shows that diverse organizations — that diversity of thought — really leads to the best results for the organization. I think we’re fortunate to be based here. Because we’re based here, we have access to such diverse talent, and so we want to make sure that we’re really leveraging that as an organization.”

CULTURE

The next pillar to which the Marlins adhere involves nurturing their employees once they’ve been hired. The organization strives for an inclusive workplace culture, actively training and providing education on important topics like unconscious bias. There is a diversity, inclusion and belonging committee that helps build and shape programming. This month, a Women’s History Month gamechangers virtual panel was held.

After Egusquiza left her last job and came back from maternity leave in 2019, she noticed a tonal shift during the interview process when she mentioned having a young son. From that point on, she made a conscious decision moving forward to lead with being the mother of a 1-year-old. When interviewing with the Marlins, Egusquiza recalls meeting with 14 people, including ownership, and feeling a sense of comfort and welcome. Both men and women alike were excited she would be sharing the job with her child. After bad experiences at previous companies, she felt supported.

Women work in front-office positions across the organization — from scouting (Alexandria Rigoli) to youth programs (Angela Smith). Unfortunately, the Marlins are the exception rather than the rule. According to the 2020 Major League Baseball Racial and Gender Report Card (RGRC) by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES) at the University of Central Florida, 28 of 30 MLB clubs had at least one woman in the role of vice president or above. The Red Sox lead the way with 12.

Mullane estimates that 30 percent of the students in the University of Miami’s sport administration program are female, a number that has grown substantially over the years. Increased interest at the college level is a positive development not only for when they’ve entered the workforce, but also when they want to grow in their careers.

“That’s one of the things that’s kind of held women back, the whole mentoring [aspect],” Mullane said. “I tell my students now, ‘If you want to be a GM, guess how many mentors you have?’ Fortunately, there is one [now in Ng]. If everybody wants to do that — and you know it’s not unusual in a class of 30 people to have 10 people say they want to be GM — [I tell them,] ‘There’s only so many of these positions out there. You better get to work.’ Middle management is fine with women, and upper management is getting pretty good. The more upper management increases, the better chances are, too.”

Egusquiza, O’Connor and Elletson, for example, are all working moms. They understand if Egusquiza needs to step away from the office to take care of something with her son. Female colleagues provide a sounding board and share similar experiences. Just as important is the allyship of men.

Jeter, who cited growing up in a household of strong women with his mother and younger sister, equated the employees in the organization to a team. Just like the players on the field, they all become a family. In order to maintain that in-office camaraderie with people working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, he scheduled bi-weekly meetings with the staff. It became a platform for shoutouts and updates on projects that teams were proud to be working on. With the external stresses, the Marlins didn’t want the culture they had established to suffer as a result. Jeter remained transparent and communicative throughout the months.

During volunteer events, including holiday food drives, the turnout was enthusiastic. Employees didn’t mind carrying heavy boxes and putting food in trunks in the parking lots around Marlins Park. It showed the level of commitment throughout the organization to give back, which ties into the final pillar of community.

“I think staying connected and being very communicative as an organization is important as far as people pulling towards the common goals and again feeling connected,” O’Connor said. “I think COVID was a tough time for that. It was odd because we’re on our playoff run and the staff’s not at the games, fans aren’t at the games, so how do you bring them into that excitement and make sure everybody feels a part of it, because they undeniably are? It really helps with the overall spirit and teamwork and camaraderie that we love to have here.”

COMMUNITY

The Marlins have focused on wellness and empowerment, particularly in youth baseball, with the majority of the work involving underserved minority communities. Earlier this month, the organization teamed up with the Positive Coaching Alliance for the “Sports Can Battle Racism” program to strike out racial inequality.

In February, The Miami Marlins Tee Ball Initiative presented by Ultimate Kronos Group returned for a third year. Over 195 teams are sponsored across South Florida, with the Marlins providing uniforms and equipment to ease the burden on people. Participation in the league includes a voucher to a Marlins game highlighting youth baseball. Both Egusquiza and O’Connor, who have seen the program built up, can appreciate the effort even more. It reminds them of the importance of the Marlins’ organization within the community, as an asset to and a connection in people’s lives. It’s both an honor and a responsibility.

Egusquiza said she never thought one of the things she’d look for in a role was her son thinking she was cool because of it. O’Connor recounted the feeling of seeing her son playing in a Marlins jersey.

“When you see your child is [at the stadium] with their team and goes, ‘My mom works here,’ you see them be proud about that,” O’Connor said, “it’s really special.”

Speaking of, both O’Connor and Egusquiza couldn’t contain their excitement for Opening Day on Thursday, when Ng became the first female general manager at the helm for a Major League Baseball game.

As a trailblazer, Ng finds it humbling. She can’t help but smile and do a fist pump when she sees women across sports shattering the glass ceiling. Alyssa Nakken (Giants), Rachel Balkovec (Yankees) and Rachel Folden (Cubs) joined their clubs’ coaching staffs in 2019-20. Becky Hammon became the first woman to serve as an NBA head coach during a San Antonio Spurs game in December. Sarah Thomas, the NFL’s only female official, was the first woman to officiate a Super Bowl in February.

More than ever, the inspirational sentiment of “If you see it, you believe it” is true. Women and men alike have taken notice, opening people’s eyes to the progress that has been made but is still yet to come.

“I like to say the possibilities are endless,” Egusquiza said. “Last year, I remember one of the things that the team talked about when we were in the playoffs is, ‘There’s still work to do.’ So that’s how I like to think about the work in this space. We’ve made so many great strides, but there’s still work to do. And I think, as an organization, clearly we’re committed to that and to continuing to develop our diverse talent and continue to recruit diverse talent. The possibilities are just endless, and I’m excited about those possibilities and about the future.”