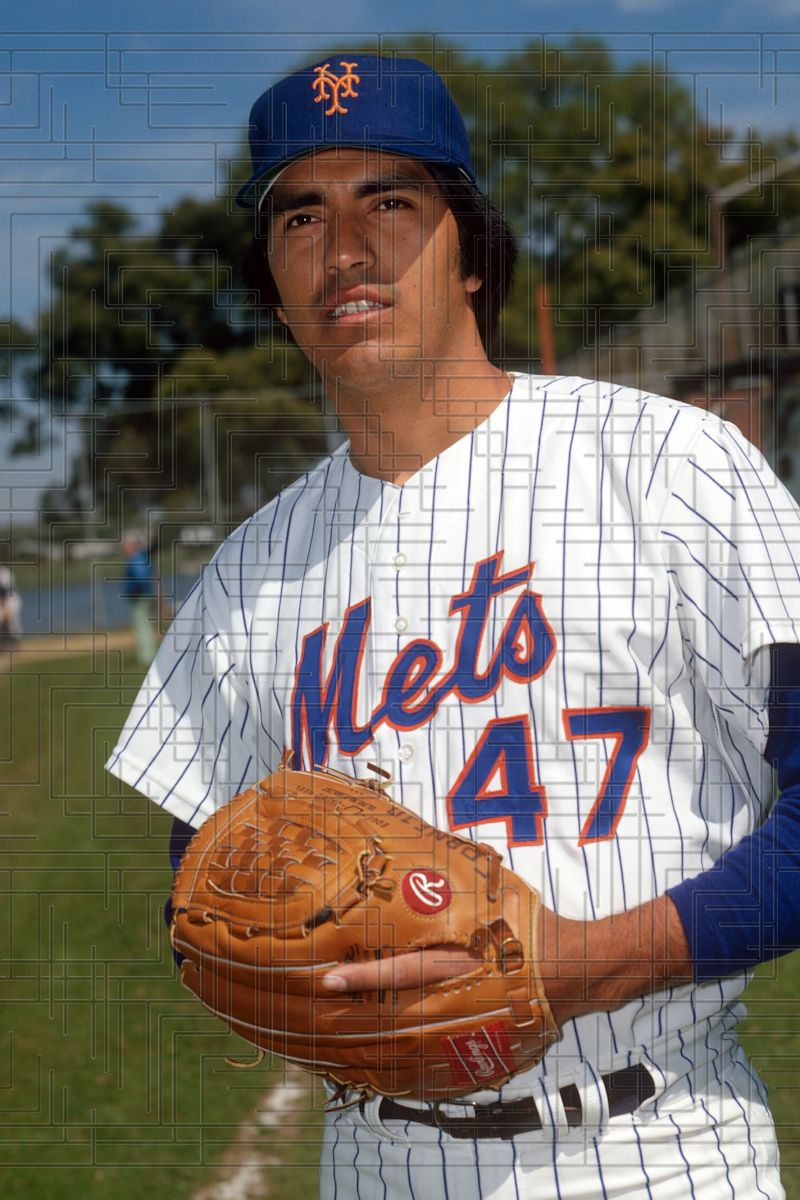

Even the most knowledgeable baseball fan probably doesn’t remember Nieves Mardie Cornejo, who played in the big leagues in 1978 for the New York Mets. A pitcher who appeared in 25 games that season, Cornejo recorded four wins and three saves for the Mets that year. In 36 and two-third innings, he had an excellent Earned Run Average of 2.45.

And just like that, his career in The Show came to an end. For his time playing the game he loved, he earned the princely salary of $21,000.

Now 70-years-old, Cornejo would most likely be a footnote in the annals of the national pastime if it weren’t for one thing: he’s now among the 609 retired ballplayers not receiving Major League Baseball (MLB) pensions.

Fast forward to the present. I am thinking of Cornejo these days because, as one of the men who walked the picket lines so free agency could occur, Cornejo has been all but forgotten by today’s players.

See, in 1980, the vesting rules for a pension changed. It used to be a player who needed four years of service to be eligible for one but, ever since, it’s only been 43 days. It was a sweetheart deal the league offered the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), which is the union that represents the current players, with one notable caveat: the pre-1980 players like Cornejo were not retroactively included.

So for the past four decades, post-1980 players like Mets shortstop Francisco Lindor — he of the 10-year, $341 million contract extension — have only needed 43 game days of service on an active roster to get a pension. And their designated beneficiaries get to keep that pension.

Instead of MLB pensions, effective April 2011, all pre-1980 players like Cornejo get is a yearly payment of up to $10,000 for every 43 game days of service they accrued on an active MLB roster. Given the time he spent with the Mets, from April of 1978 to September of that year, it’s more likely that Cornejo gets a bone of $2,500 thrown at him. And that’s before taxes are taken out.

What’s more, the payment cannot be passed on to anyone. So when Cornejo dies, whoever his designated beneficiary is will receive the bone he’s being thrown. The irony here is that Cornejo’s son, Nate, who pitched for the Detroit Tigers for three seasons, from 2001-2004, will be collecting an MLB pension at the age of 62. Other father-son pairs in this unique group, in which the sons are eligible to receive pensions, but the dads are not, include Mike and Dave Stenhouse; Hank and Ryan Webb, Steve and Jason Grilli, and TJ and Nelson Matthews.

But do you hear this issue being bandied about in the collective bargaining negotiations (CBA) now going on? Of course not. Under the terms of the CBA, the league doesn’t have to bargain about the pre-1980 players unless the union first broaches it. As for the MLBPA, it doesn’t owe these retirees what is known as the “duty of fair representation,” i.e., once they’re out of the game, the union doesn’t have to provide legal guidance or counsel to them.

Lockout or not, what makes this unseemly is that the national pastime is doing great financially. The average salary is $3.7 million, which is the minimum salary is $575,500 and, in its 2021 edition of MLB team valuation, Forbes reported that each of the 30 big-league clubs is valued at an average of $1.9 billion.

Just increase the bone thrown at these retirees to $10,000 a year. Are both MLB and MLBPA suggesting they can’t afford to pay these men more?

If anyone can help these men, it’s Lindor who, as a member of the eight-member players’ union executive committee, is in a position to go to MLBPA Executive Director Tony Clark and insist that this injustice be remedied once and for all.

Listen, nobody begrudges anyone his money. This is, after all, still a capitalist country. But if it weren’t for the guys like Mardie Cornejo, who endured labor stoppages and went without paychecks so free agency could occur in the first place, do you think Lindor would be in a position to be getting the kind of big money he’s making?

Lindor’s nickname is “Mr. Smile.” By doing the right thing, he can put a smile on the face of Cornejo and 608 other men.

___________

Freelance writer Douglas J. Gladstone of New York is the author of A Bitter Cup of Coffee; How MLB & The Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve.