The music’s queued, the spotlight poised: At Presque Isle Downs, they wait with restless pep to toast a priceless racetrack deed. Jockey Mario Pino nears his 7,000th victory, a treasured artifact in an ancient sport. So why does this pending metaphorical ribbon on a grand career feel like a slipknot?

On the south shore of Lake Erie, time and circumstance mark a collision course. Pino postponed retirement this year solely to hike this racing summit, a view only nine North American jockeys have witnessed. Once track management began touting and flouting his looming ascent toward the magic number, Pino dutifully resolved to make history expressly at Presque Isle. Hence, this strange conundrum.

A 60-year-old grandfather of two, Mario Pino has reduced his workload, rearranged his riding itinerary and pledged to retire after No. 7,000. A score Monday gave him 6,996. In sum, he needs four wins over the final three days of the Presque Isle meet that ends Thursday, which prompts a thorny question: How does one ride off into the sunset if darkness has fallen?

“I’m supposed to win my 7,000th here,” Pino said by phone Monday from the Erie, Pa., track. “They’ve really promoted it. They’ve been talkin’ about it and talkin’ about it. Now, they’ve got plans — they’re gonna make a big deal about it here. So if I don’t do it, I’ll have to wait till next year. I kind of owe them.”

Melodramas go screwy when the story’s dramatic climax and conclusion happen simultaneously — and so our quiet, mannerly race-riding protagonist finds himself in a scripted bind. Should he manage four victories before Friday, Mario Pino will ride no more and return a new retiree to Delray Beach, Fla., with wife Cristina. If not . . .

Does he maintain his unspoken commitment to Presque Isle? That would mean waiting seven months for the 2022 summer/fall meet while time conspires against him. Pickleball, jogging, weightlifting, yoga help keep Pino a physical marvel, but advancing years invite new pounds. Where he tacked 114 during his Maryland heyday, 1980s through 2011, Pino now tacks 119.

And what of his accustomed schedule? The past few years, after a five-month winter break, he’s begun the season at Gulfstream Park in spring to relight the riding spark and regain fitness. What if he should finish Thursday a victory short? What then? Does he resume the quest at Gulfstream Park next year half-wary to win?

“It’s sorta crazy,” Pino said. “I’m kinda like in the middle here with all this.”

Still driven to ride, he acknowledged that The Number, more than anything, compelled this pursuit. Pino said he was ready to put it in park after he finished the Gulfstream meet at 6,961 late in June. Then he had a conversation with trainer Wesley Ward.

“Listen, Mario, you’re 39 wins away,” Ward told him. “You can’t leave it on the table. You have to push yourself to do it. Here. There. Somewhere.”

The words echoed. “I was kinda skeptical to try,” Pino said. “Then I got to thinkin’. . . “

Presque Isle seemed right for the task. A staple there since 2012, Pino had connections, value, continuity. He liked the synthetic track, and the manageable field sizes would prove no hindrance.

He also knew the slope. When you’ve ridden more than 42,000 races, you appreciate the challenge of winning 39 times over a three-month, 55-day meet. Pino managed 17 victories at Presque Isle last year, according to Equibase, in a meet shorter than three months, 48 the five-month meet of 2019.

He has five prospective mounts Tuesday, seven Wednesday, eight Thursday. From 20 potential horses, any four can deliver him.

Trainer Ferris Allen wouldn’t bet against him. He and Pino were professional acquaintances through Pino’s first 20 years in Maryland, then became friends when they shared a house for the Colonial Downs summer meet around 2000 and years thereafter.

“He has a real passion for winning,” said Allen, once a William & Mary second baseman who still plays competitive hardball at 70. “If you’re playin’ cards with him, playin’ basketball with him, you can see it in him and in any of his kids — they’ve all got it too. . . . His daughter Victoria whipped my ass in H.O.R.S.E. She was, like, 12.

“The thing about Mario is, he’s always been able to do it in a thoughtful, kind, yet aggressive way. He’s so serene in everything he does, and if you think that means that he’s meek, then you’ve misread him. Because he’s not. I don’t know anybody that likes to win better than he does.”

Pino’s numbers bespeak a career of near-tick-tock constancy. As horse-backing meteors Kent Desormeaux, Edgar Prado and Ramon Dominguez flashed through Maryland, Pino effected a steady orbit: He surpassed 1,000 mounts and finished among the state’s top five riders by victories every year for a quarter-century, from his 1979 rookie season (as runner-up for the national apprentice-jockey title) through 2003. Persistent returns in a perilous profession.

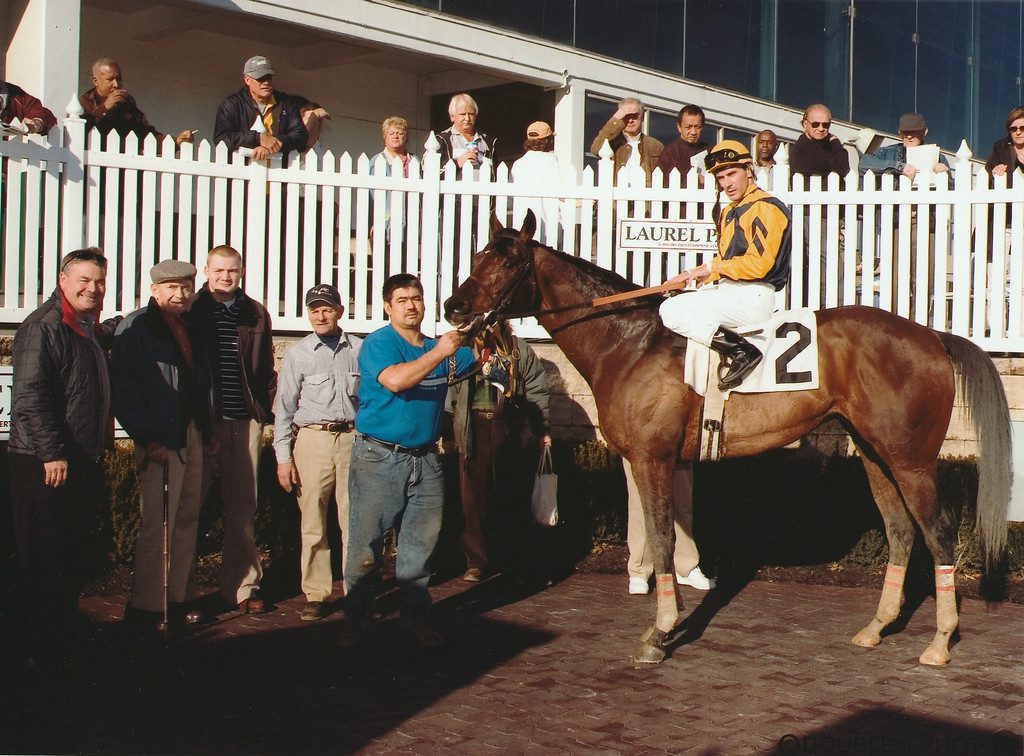

On New Year’s Day, 2011, trainer Allen greeted Eric Camacho in the Laurel Park paddock and commended the jockey’s newly minted 101-win season. “Now, if you can just do that for 65 years,” Allen told him, “you’ll be like Pino.”

Mario’s tasted the big-time with Grade 1 winners Hard Spun, Bishop’s Ring, and Wildcat Bettie B and shown everyday cordiality worthy of the 2016 Mike Venezia Award for “sportsmanship and citizenship.” His easy way with people conveys to horses: Even as a kid in Delaware, dad hoisting him atop a pony, Pino understood the nuanced human-equine bond, the shared objectives, the good that grows from quiet hands.

“I would say to myself, ‘Wow, I have this little gift here. I don’t have to do much with my hands, and the horses do better,’” he said. “I’m not braggin’ on myself, but I’ve had it from the very beginning. And it’s true today: The horses respond with you doin’ just little things.”

In a race, he furthered, “There are times to be strong, and times to be relaxed. Times to be riding a horse really hard to make him go, and times where you have to have the horse-sense that you need to nurse him to the wire instead of beatin’ him.”

As the finesse rider finds a chaotic stretch run, one dogged question stalks him: With the finish line four wins away, and blessed retirement at stake, can he cue the music and the spotlight before Thursday’s curtain falls?