[ad_1]

With six wins from their first nine official games, scoring 22 goals, and a friendly win over Atletico Madrid, Feyenoord have had a pretty good start to the season. Especially considering the fact that their new manager Arne Slot is trying to implement a completely new style of play.

The previous coach, Dick Advocaat, had Feyenoord play in a defensive block with very intensive man-marking duties. Slot chooses to have Feyenoord press high-up while also preferring to build-up from the back and applying intensive counterpressing when possession is lost.

Therefore, I reckoned it would be an interesting case to take a deep dive into Feyenoord’s tactics utilised this season. On one hand, to see how one of the most exciting teams in Dutch football is playing. And on the other hand, to examine what issues Feyenoord are running into during this transition from a defensive low block side, to a team that mostly plays with the ball. As this is a transition more teams and coaches are trying to make, on different levels of the game.

I have structured the article by the four main phases of the game (possession – transition from attack to defence – defending – transition from defence to attack). Within each phase I will describe how Feyenoord plays within that particular moment, before describing some issues the team has run into during their first matches this season.

Before we start, I want to give a quick heads up: I wrote this piece in September-October, but life gets in the way. Therefore, it hasn’t been uploaded until now. Feyenoord’s play has (obviously) evolved. For example, Aursnes is now a regular starter in midfield and most teams have started to adapt to Feyenoord’s style of play. Due to the moment of writing not everything is up-to-date, but I still believe it gives a good insight into Feyenoord’s plan under Slot and the changes he made to their style of play.

By: Evert van Zoelen

Possession

I subdivided the possession stage into four categories: build-up, attacks over the right side, attacks over the left side, and finally attacks through the centre. In each category, I will start by discussing the common patterns in Feyenoord’s play and then analyse common problems during this moment.

Build-up

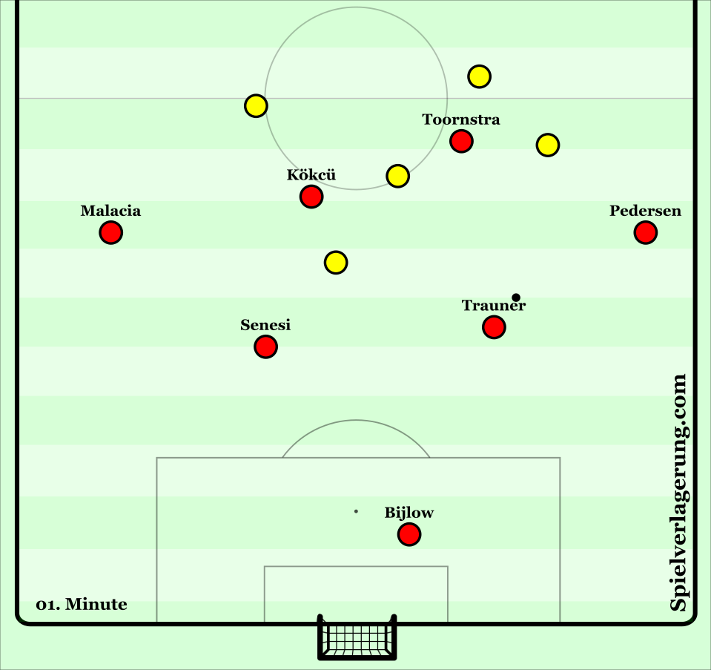

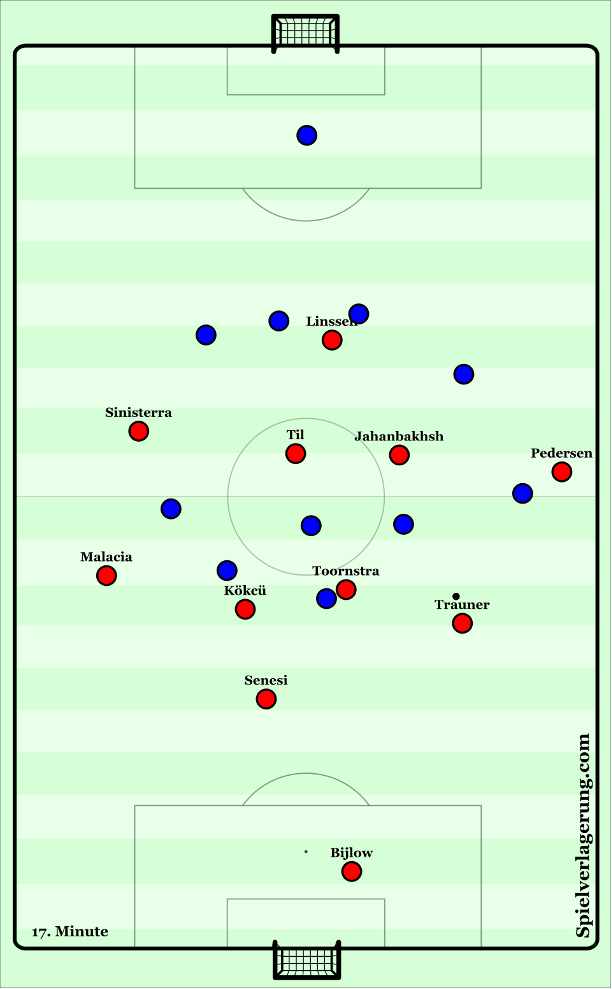

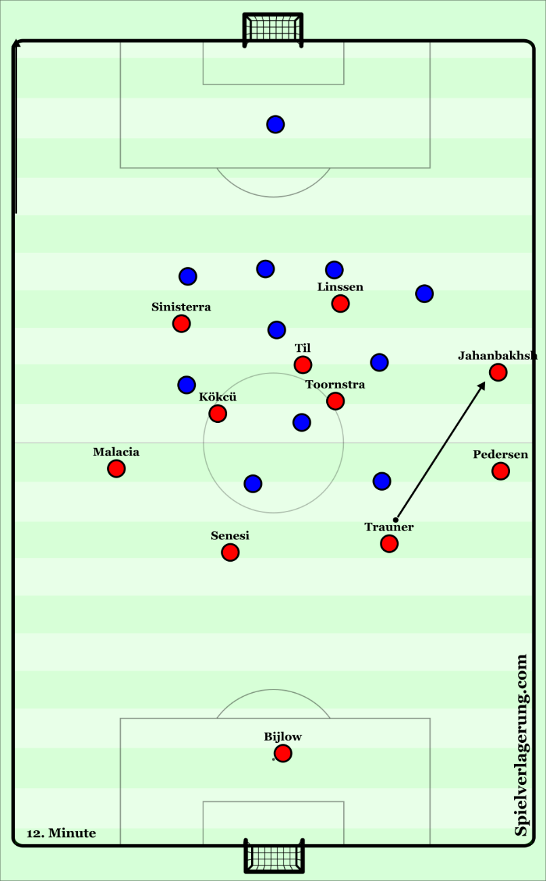

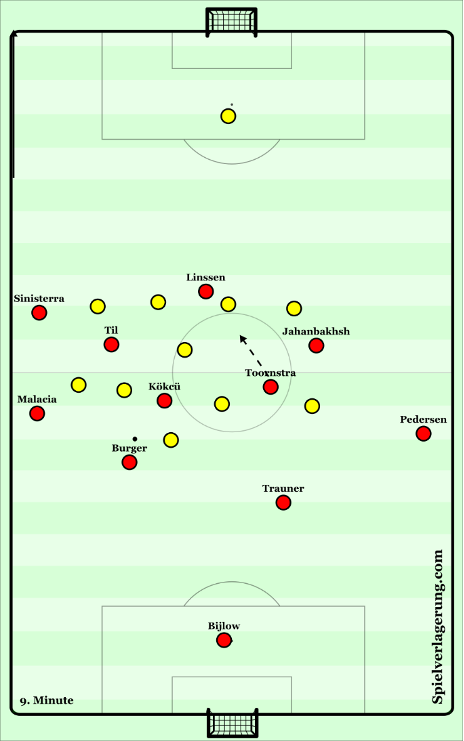

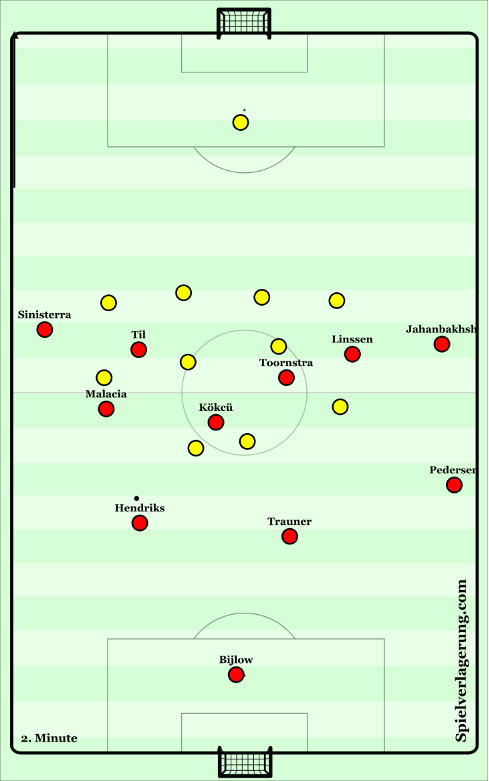

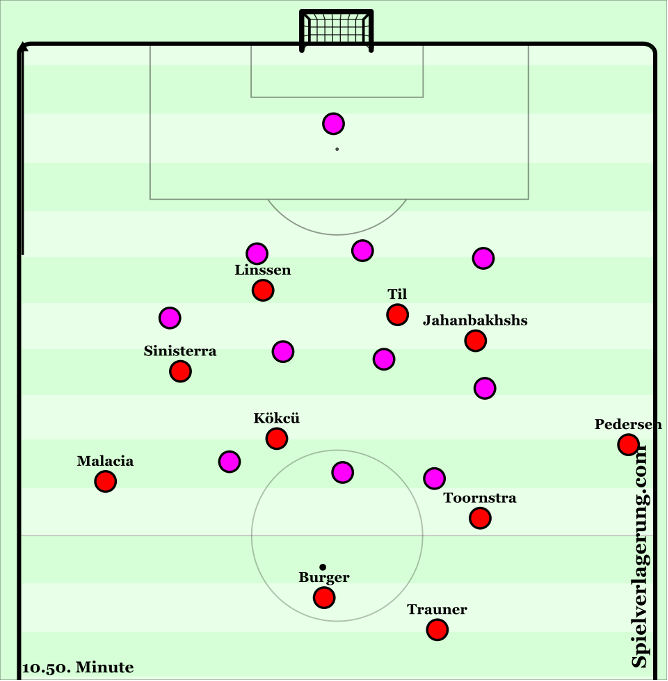

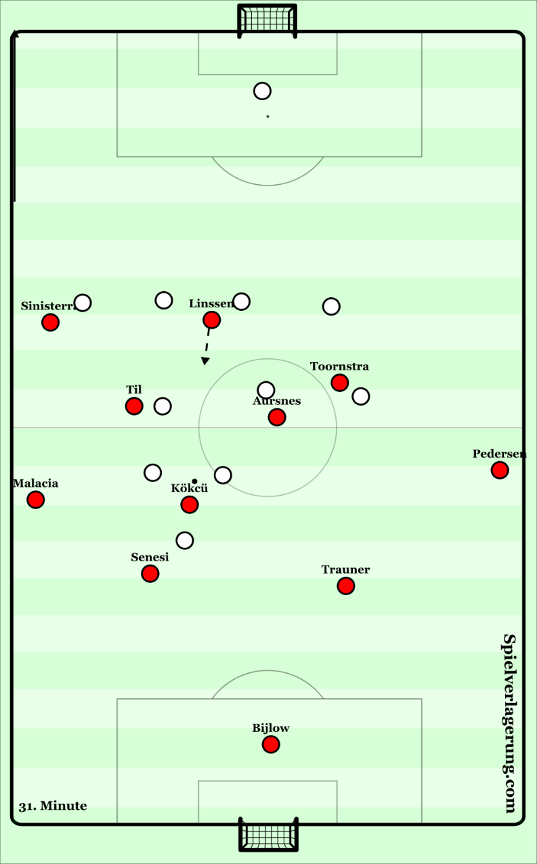

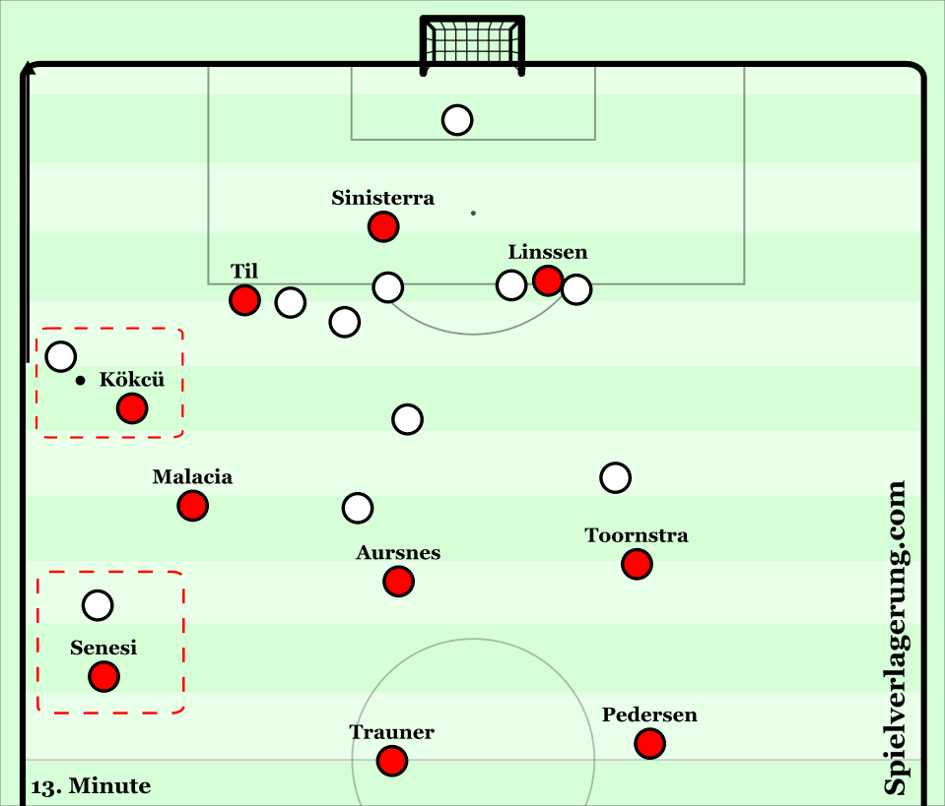

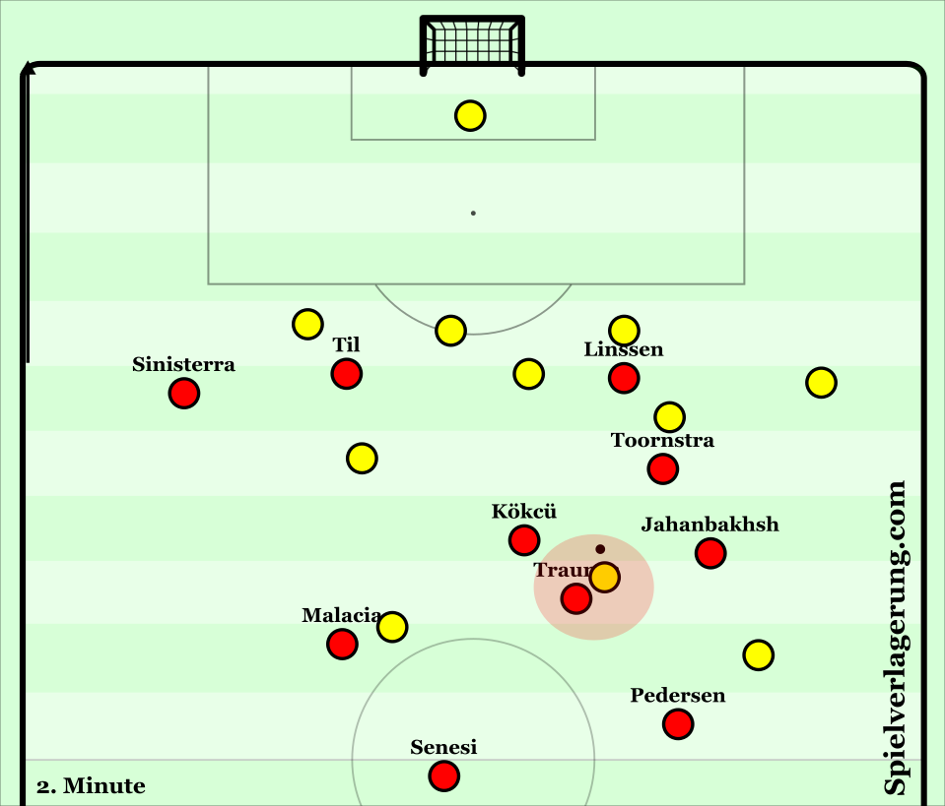

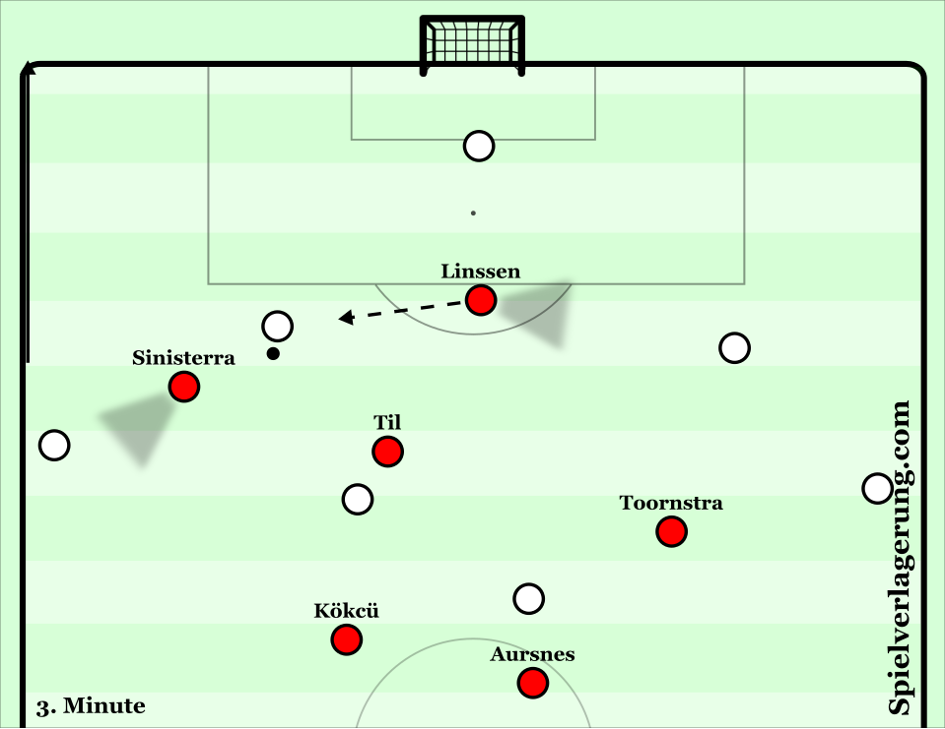

During the build-up Feyenoord mostly use a 2-4 shape. The two central midfield players, Orkun Kökcü and Jens Toornstra, take up positions in between the first two pressing lines of the opponent and try to receive between those lines. The fullbacks won’t go too high during the initial stage, in order to provide emergency support in case the centre back on the ball doesn’t have any options.

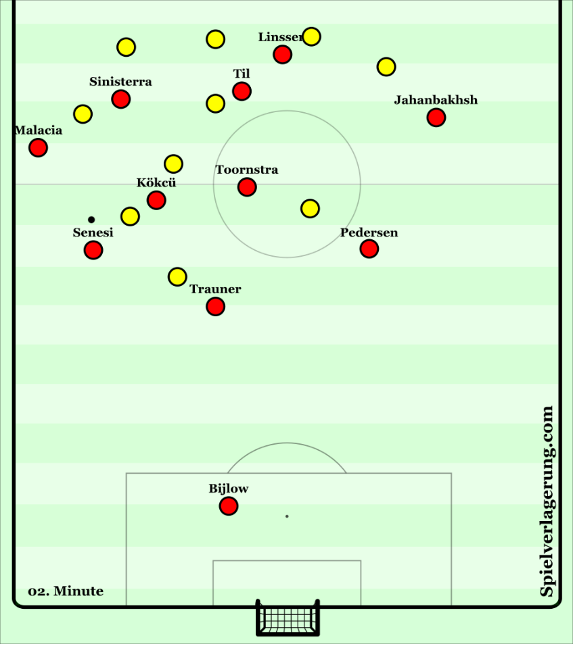

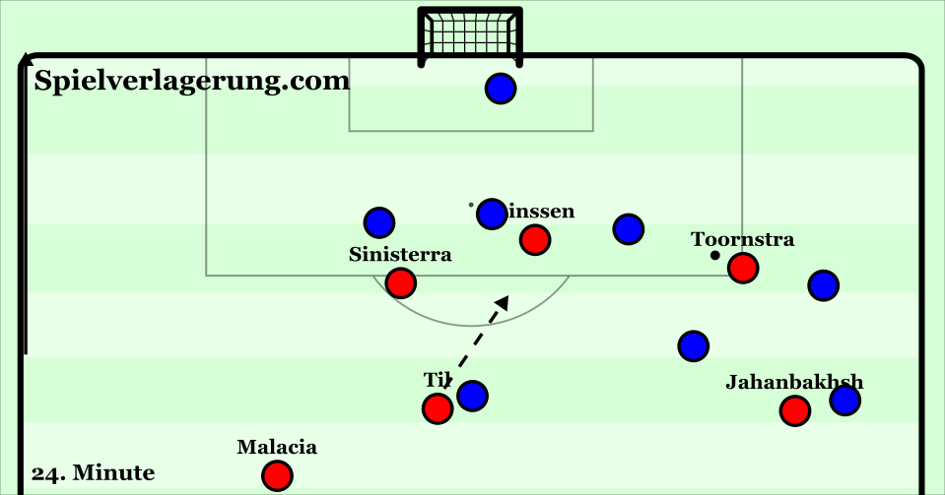

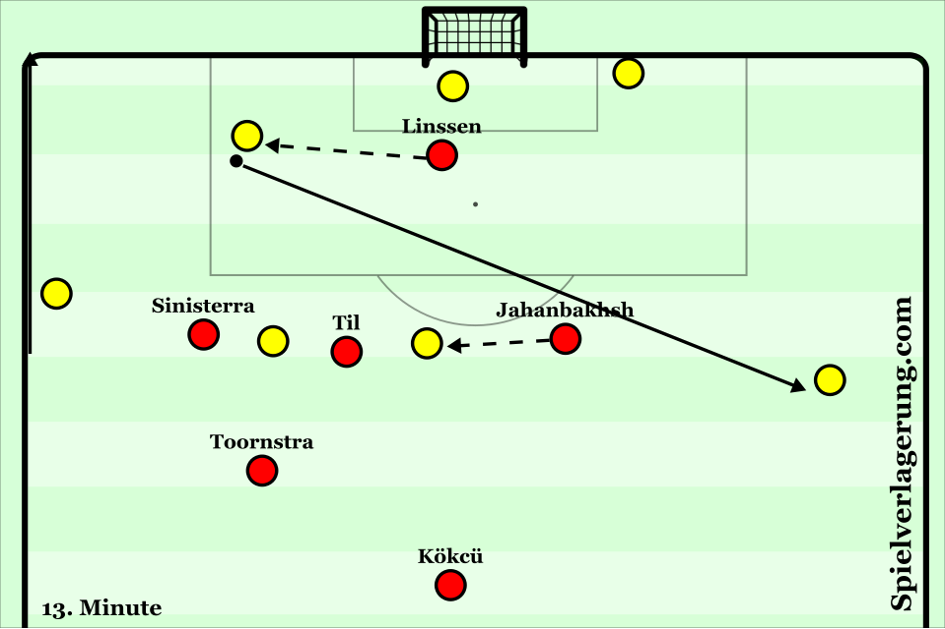

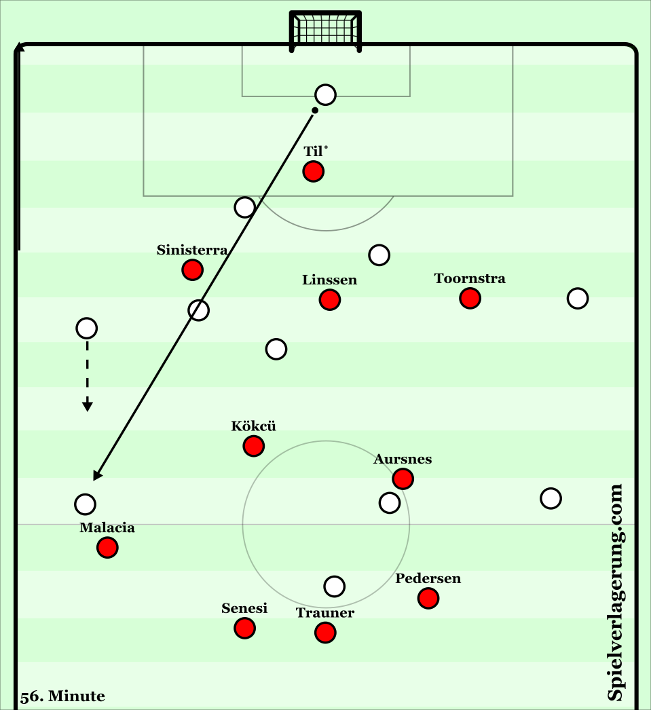

In the ideal case, the centre back is able to advance with the ball in one of the halfspaces. In which case Feyenoord move into a 3-2-4-1 shape. The fullback on the side of the ball moves into a higher position, with the winger on the ball-side moving into the halfspace. Meanwhile, attacking midfielder Guus Til moves into the centre or even the far-halfspace, with the far-winger maintaining the width. On the side of the ball, this creates a diamond-like shape with the centre back on the ball, the fullback, the winger and the central midfield player.

When this happens, Feyenoord’s central defenders will look to play the vertical pass through the halfspace into the winger. The winger then has two main options: either find the fullback as the third man, or find the central midfielder as the third man. While immediately turning is also an option when the defensive system of the opponents is not able to immediately press him.

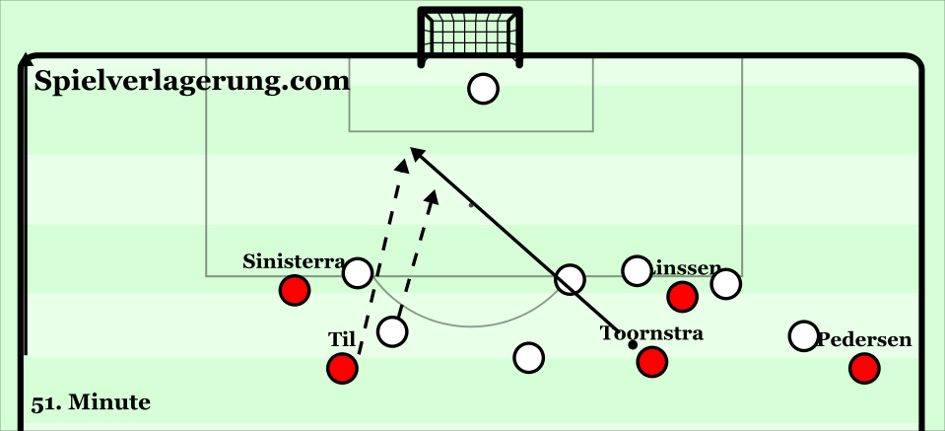

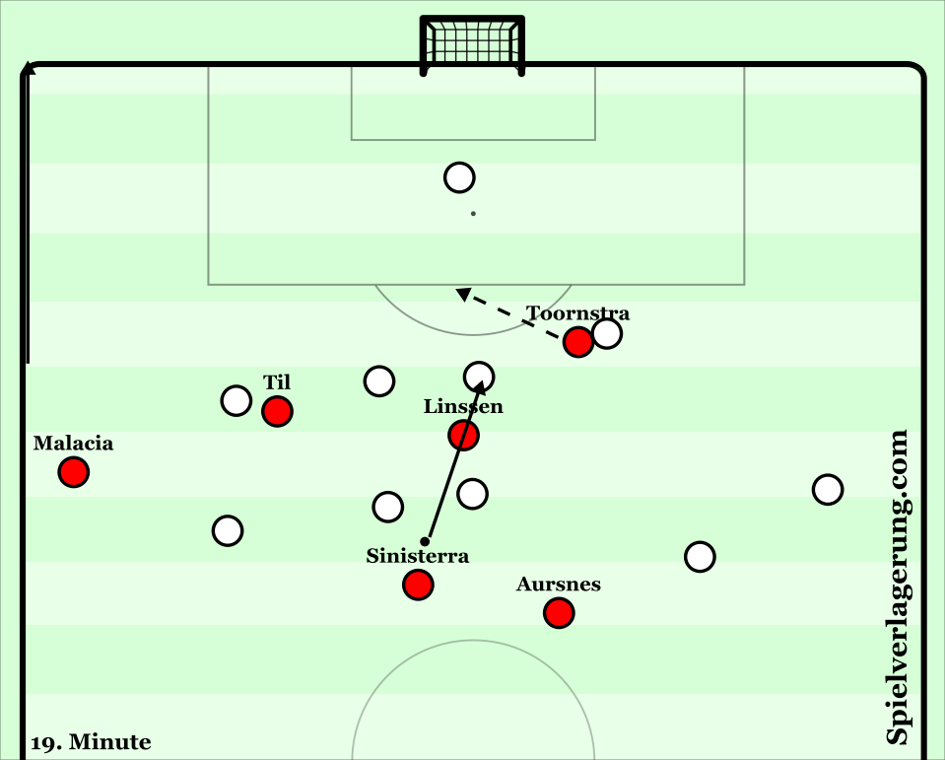

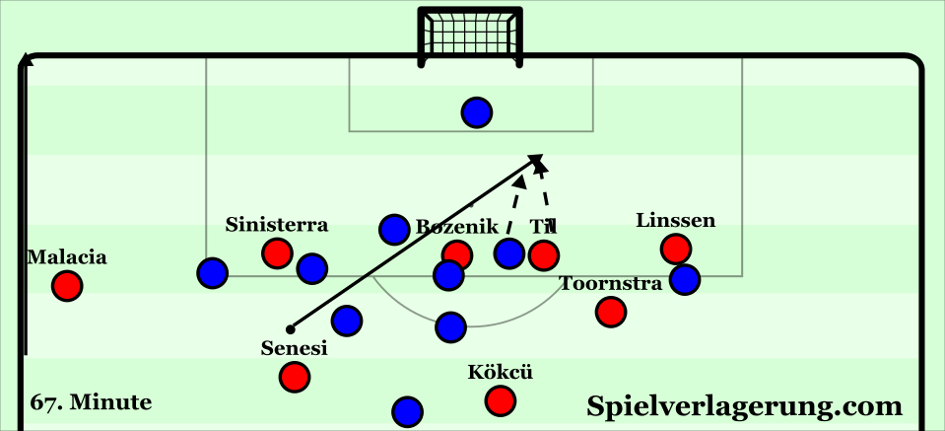

Something Feyenoord added during the later matches are runs in behind when the winger moves into the halfspace. On the left side, when Luis Sinisterra moves into the space in midfield it is usually Til who makes the run in behind towards the left side. On the right this is usually done by Toornstra, the central midfield player.

Arne Slot is a big advocate for runs in behind, something we will discuss later, and has stressed the importance of them throughout his career. Also, in this situation, their added benefits are shown.

When Feyenoord’s winger moves into the halfspace, it is usually the opponent’s fullback who will try to follow the movement. However, when this decision is made, it leaves an imbalance in the last line of the opponents as the fullback and central defender are no longer on the same height. This can then be exploited by making a run in behind. These movements also create multiple options for the central defender on the ball. When the player between the lines is marked, usually the option to play in behind opens up. While this also works vice versa, when the fullback drops back to defend the player moving into his zone, he isn’t able to also follow the player moving between the lines who is therefore able to get free.

During the build-up, Feyenoord have a preference for starting on the right side and finishing the attack on the left, which makes sense when looking at the individual qualities of the players. On both the left and right side, Feyenoord have a good ball playing central defender with Marcos Senesi and Gernot Trauner. However, on the right side Alireza Jahanbakhsh is much more comfortable with moving into positions between the lines, than Luis Sinisterra is on the other side. Sinisterra is more of a ‘true’ winger, preferring to receive near the side and starting his actions from those wider positions. In addition, Til seems to have a preference for playing from the left halfspace, while the striker, Bryan Linssen, usually moves towards the right side.

At times, this 2-4 shape during the build-up is traded for a 2-3 shape, with Toornstra or Kökcü moving towards one of the sides. This is usually done when the fullback on that side has already taken up a higher position and is therefore not able to provide support to the central defender on the ball.

In case Feyenoord isn’t able to build from the back, their goalkeeper, Justin Bijlow, plays a long ball usually aimed towards the left halfspace. Bijlow has a very good long pass, usually being able to play it towards the chest of one of the forward players after which another player comes directly behind the first player to receive the second ball. In addition, Linssen is very smart in positioning himself to win second balls. So even when the kick isn’t 100% accurate, he has more than once been able to find a way to still get on the ball. Which we could see with his goal against Willem II, for example.

Don’t play it to the fullback

One of the main diseases that struck Dutch football during the last ten years or so, causing the national team to not qualify for Euro 2016 and the World Cup in 2018, and most Eredivisie teams to be out of Europe rather soon, is the willingness to constantly build-up over the fullbacks. Dutch teams want to build-up every single moment of every single day, and with a lot of teams closing down the centre this often causes them to build over the sides. However, since fullbacks are quite isolated on the side of the field and therefore rather easy to press, this doesn’t always go as planned. Therefore, we see the more ‘modern’ Dutch coaches like Eric ten Hag and Arne Slot use field occupations with their teams that basically make it impossible to build-up this way.

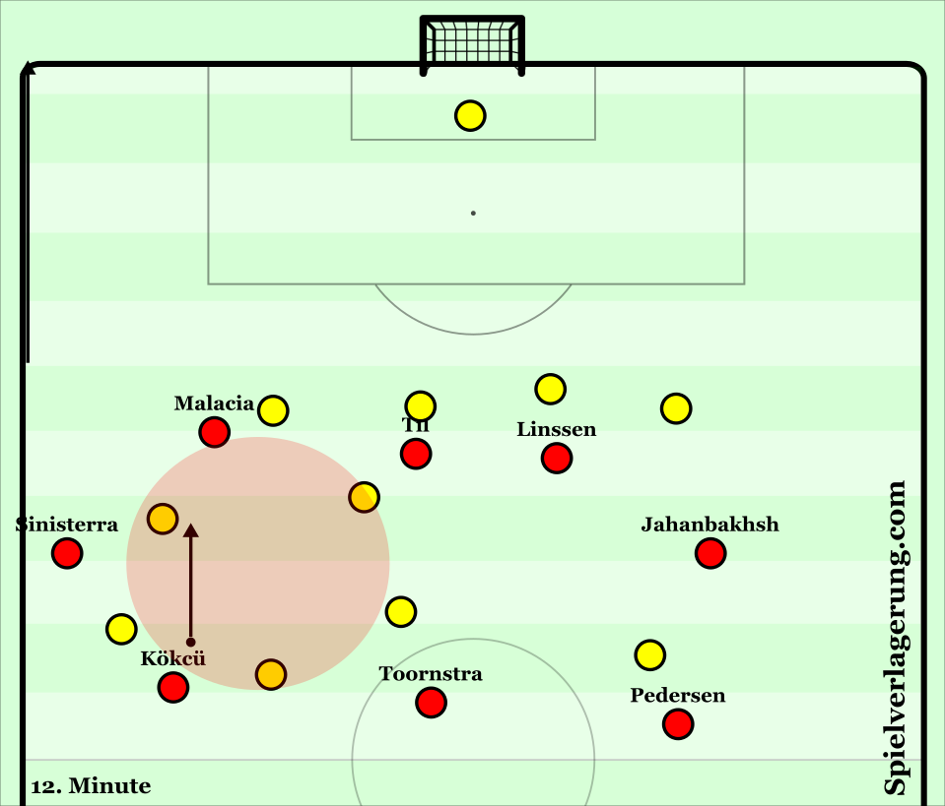

At Feyenoord, Slot does this by utilising the principle that only one player can be in the outside lane of the field. The fullback is able to stay wide when the winger moves into the halfspace, as we have seen above. While another pattern we often encounter is the fullback makes the diagonal run into the halfspace, allowing the winger to drop somewhat and receive the pass from the central defender.

The advantage of this type of pass is that it creates much more diagonal angles for the team, allowing the winger to receive with an open body position and advance the play forwards. In addition, the fullback can just take over the role as the top of the diamond in the halfspace. We can often see that Slot doesn’t really seem to care which player is in which position, as long as all positions are occupied. For example, Tyrell Malacia on the left often makes the run to the space between the lines, allowing Sinisterra to keep a wider position.

Overload during build-up

Slot always wants some kind of numerical overload during the initial stage of the build-up. Within the 2-4 structure, Feyenoord usually have this with their central defenders, fullbacks and midfielders.

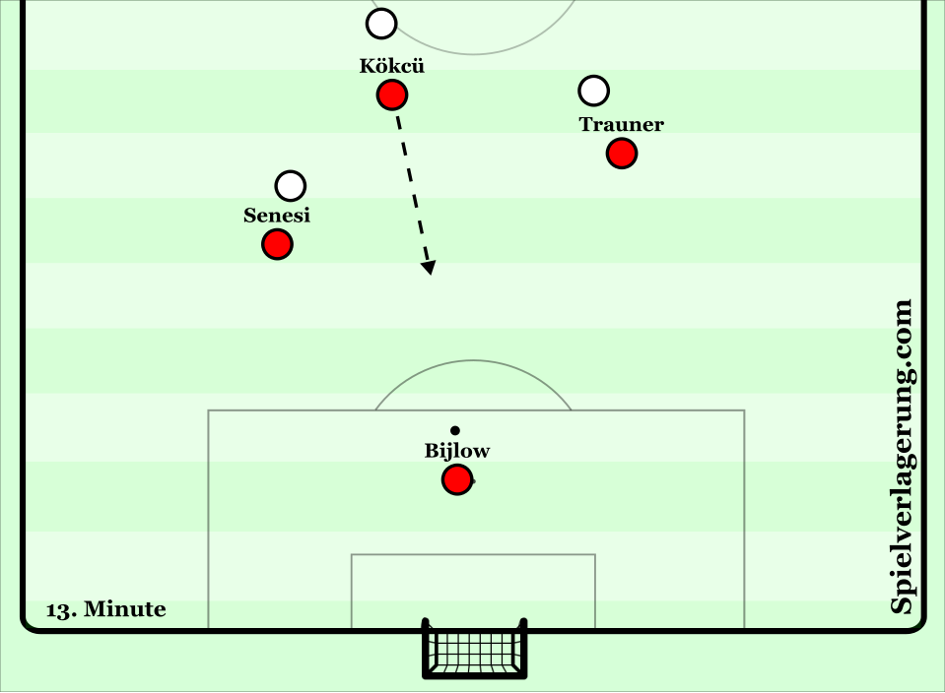

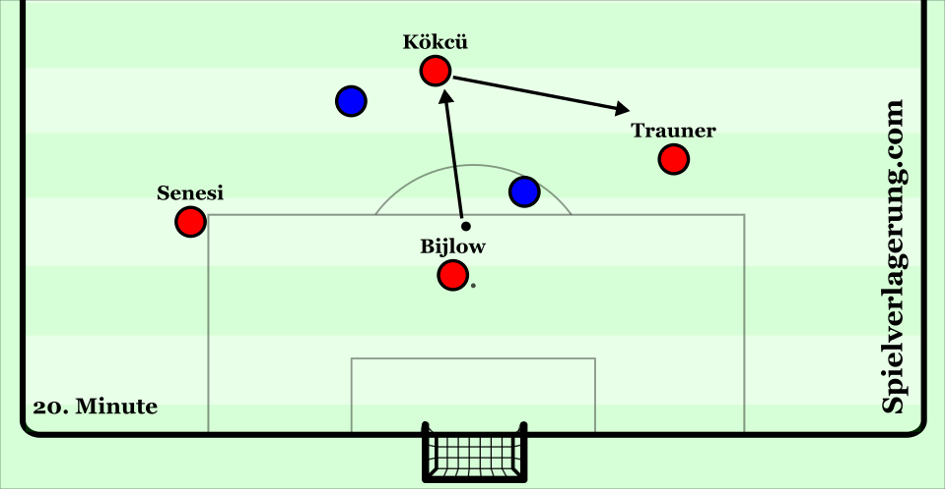

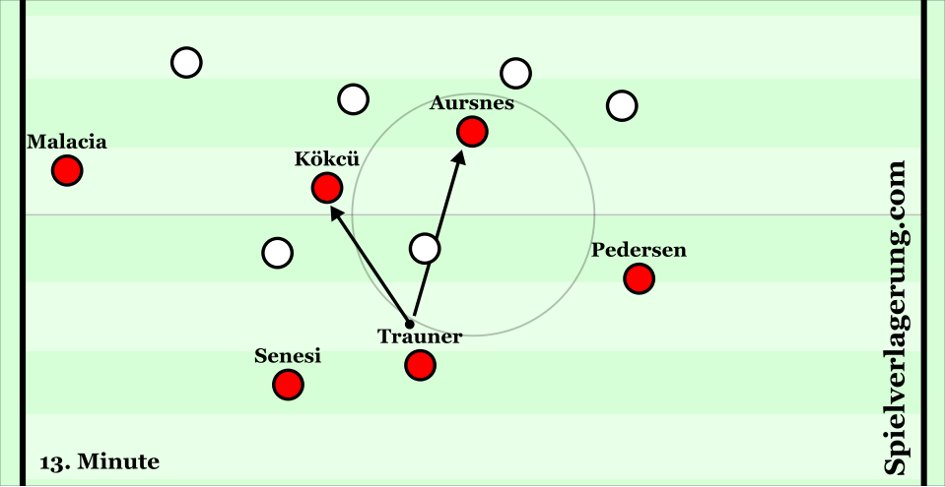

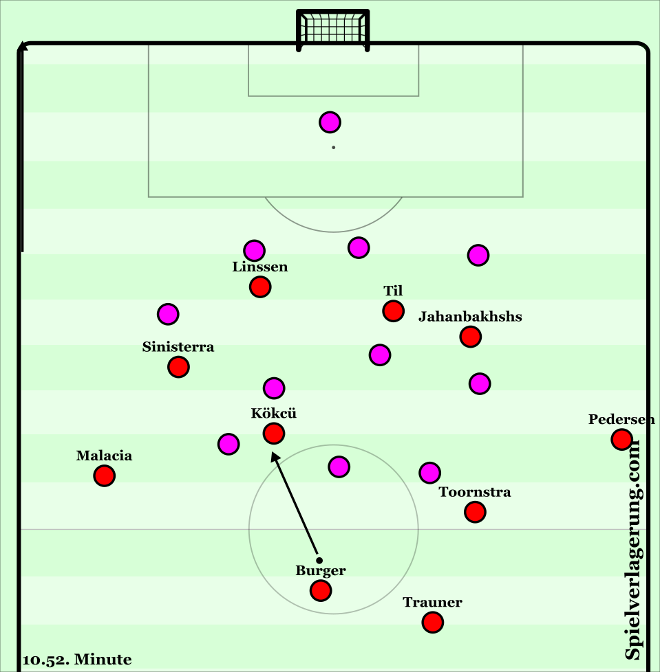

Feyenoord lose this advantage when the opponents are pressing high up and putting pressure on both their fullbacks. In these instances, one of the central midfield players drops back into the space between the two central defenders. Usually, this role is occupied by Kökcü, who is the most creative of the two.

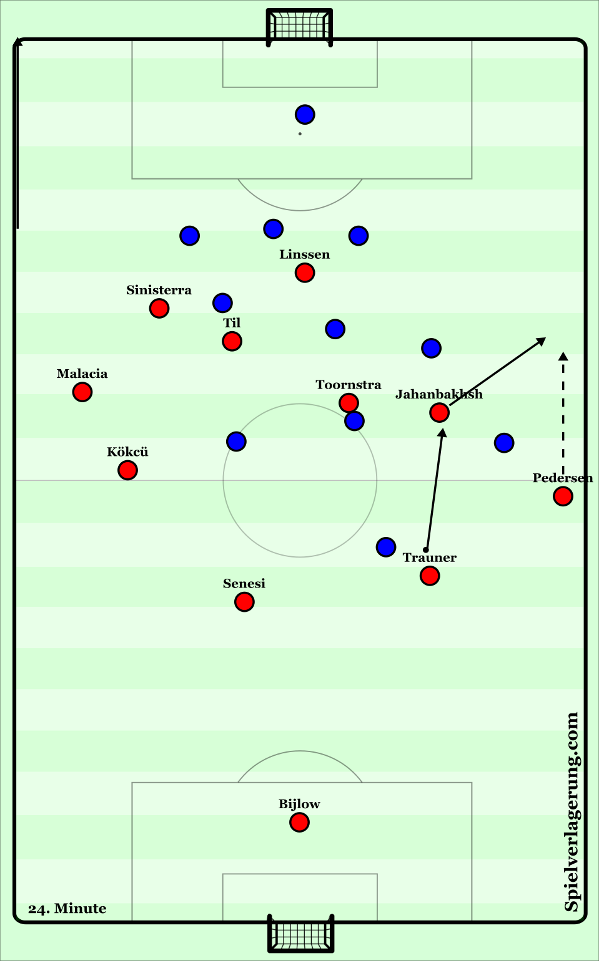

However, what is interesting to note is that Feyenoord only utilise this form to create a numerical advantage in their own third. Feyenoord don’t create a 3v2 by dropping one of their midfielders back in the middle third, unlike teams as Barca and Real who use this kind of pattern with Kroos and Busquets in the past. The only instance in the middle third we see one of the midfielders drop back, is when one of the central defenders dribbles into midfield and their position at the back has to be secured. This mainly happens on the right, with Trauner dribbling into midfield and Toornstra taking over his place.

Both of these situations have been developments over the last matches. During the first matches, neither midfielder would drop back to create the 3v2 overload at times, while the restdefence also wasn’t always secured when one of the central defenders moved into midfield.

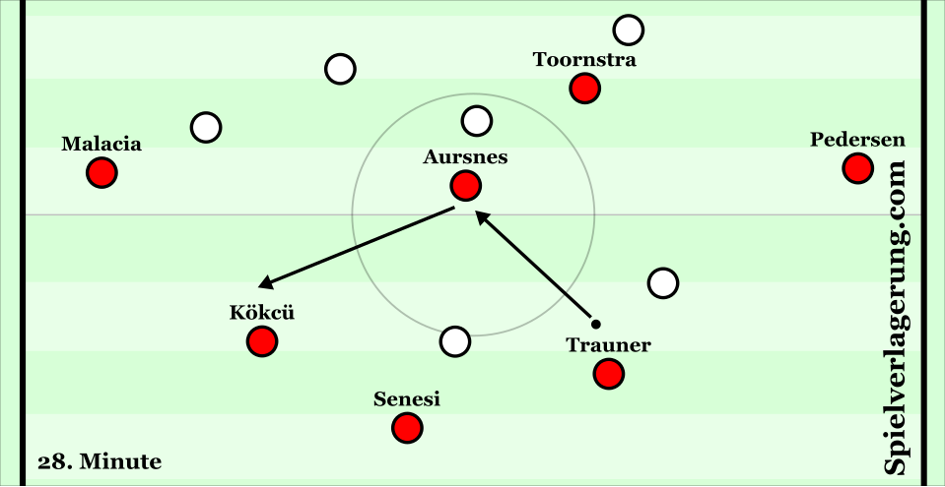

Building up in the opponent’s half

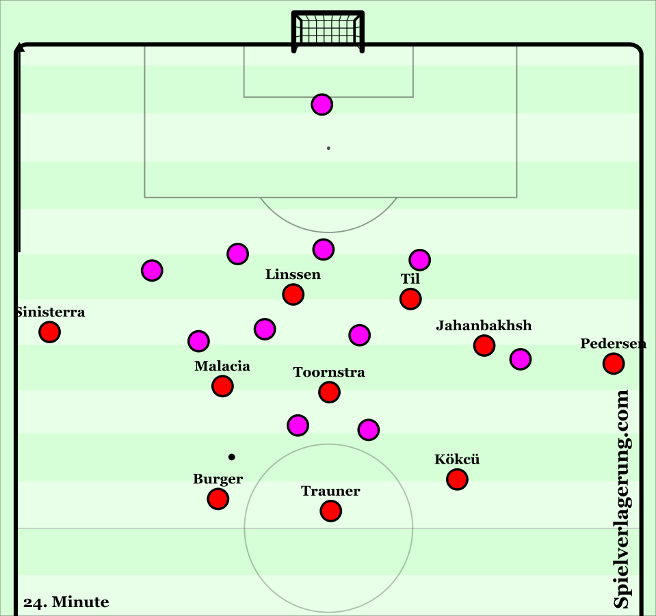

Once Feyenoord reach the opponents half, or when the opponents game plan is to drop back into a middle- to low block, Feyenoord’s build-up structure becomes a diamond like shape with the two central defenders and the two central midfielders. Both fullbacks are able to get into more advanced positions.

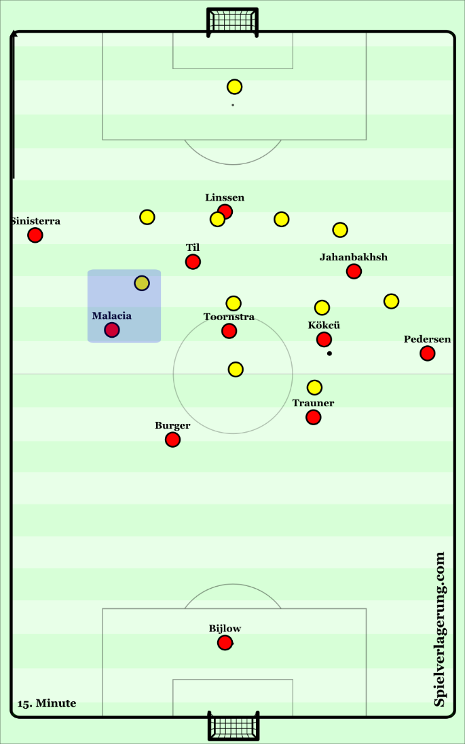

Far-fullback takes the restdefence

When play progresses over one side, the fullback on the far-side of the field immediately moves into the halfspace in order to take up a good position in case Feyenoord lose the ball. Feyenoord try to immediately press the opponent upon losing the ball, something we will go into later, and by moving into a central position the fullback has a much better access to jump forward to the opponent’s winger compared to him staying in the outside lane.

Alternative shapes

In addition to their main shape, Feyenoord have made small adjustments during games in order to attack certain weaknesses of the opponent.

In the conference League game against Elfsborg, Feyenoord mainly build-up from a 4-3-3 type of structure with just one ‘6’ and two ‘10’’s. Kökcü stayed in the six-space, with Til being positioned as a 10 in the left halfspace. Toornstra moved higher to position himself between the lines in the right halfspace. The main reason Slot seemed to favour this solution was the fact that Elfsborg defended from a 4-1-4-1 formation. By switching his midfield, Slot created a 2v1 against Elfsborg’s defensive midfielder, forcing them to adjust.

Similarly, against the 4-4-2 shape of Utrecht, Slot switched to a 4-2-2-2 type of shape. Til stayed in the left halfspace, with Linssen moving into the right halfspace. The wingers stayed wide, and Feyenoord played with a double ‘6’ again. The idea behind this seemed to be to create wide overloads, however this didn’t really come to fruition.

Problems during build-up

As a team which has just transitioned to a possession-based style, Feyenoord encounter multiple issues during the build-up. Most of these are, in my opinion, quite characteristic for teams undergoing this transition. Therefore, I hope that coaches reading this will not just see this as mistakes Feyenoord are making, but recognise the patterns laying underneath, and use those to analyse their own teams when undergoing a similar transition.

Lack of third man combinations

One of the main issues Feyenoord have is that the players don’t recognise third man combinations. On paper this type of combination seems simple: player A plays to player B who quickly plays it to player C. However, in order to execute this at the highest-level multiple prerequisites have to be met. For example, all three players need to recognise the third man combination, recognise which of the players they are, the passing needs to be very precise, and the second player needs to be comfortable receiving while being pressed from behind.

Especially in their own third, we can see that Feyenoord players have trouble recognising and executing this type of pattern. This causes problems with playing out underneath the opponent’s press. As most teams want to keep a +1 at the back, they press in an underloaded fashion. This means that not all players are covered at once, with these players usually being defended by a covershadow. When the attacking team recognises these situations, they are able to reach the free player(s) through a link player, aka a third man combination.

As Feyenoord often lack the recognition of this situation, they either make a difficult pass to someone who is positioned on the side that’s being pressed. Or, they just go long and aren’t able to play out underneath the press in a controlled way.

This lack of third man combinations isn’t just in their own third. In the middle third these opportunities are also missed. But as the numbers in those situations are often equal between the attacking and defending team, the opportunities in those situations are much less common.

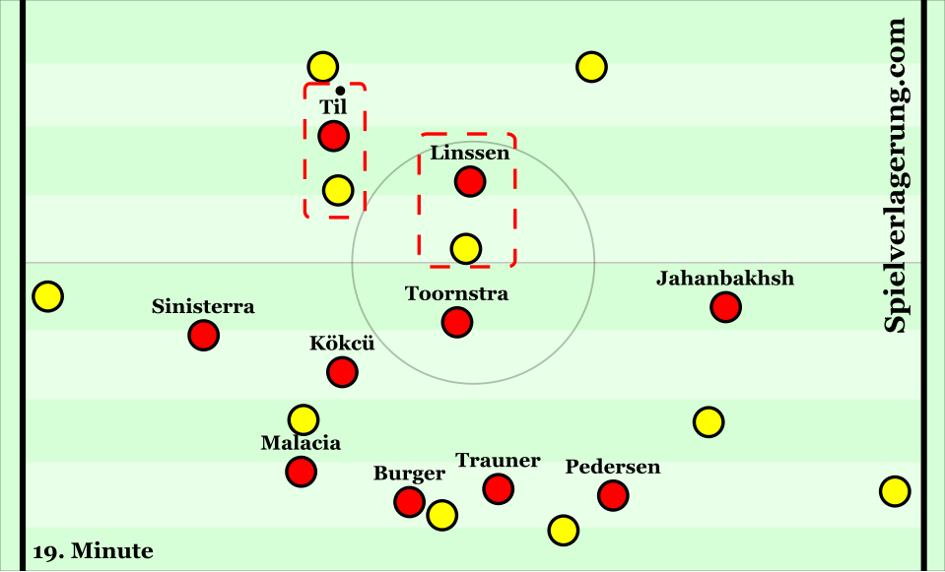

Positioning of the midfielders

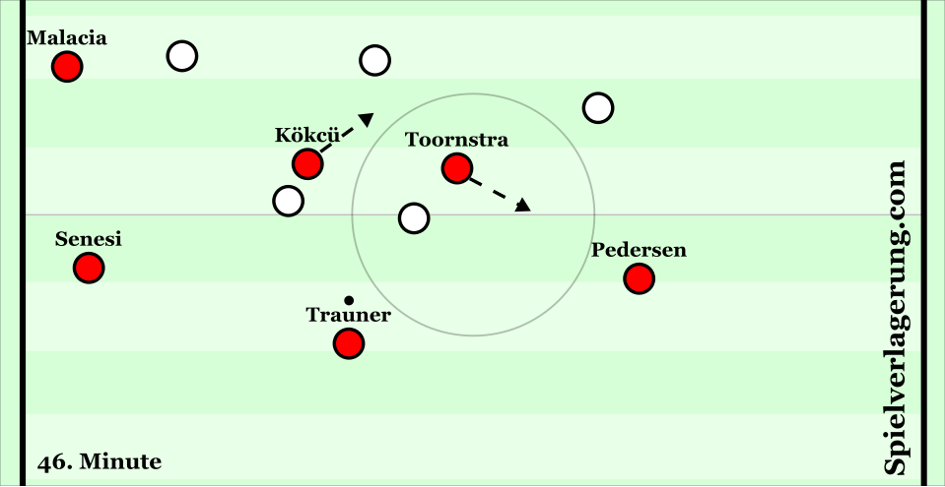

This is one of the problems Slot was able to fix quite early on. During the first couple of matches, Toornstra and Kökcü would form a double six, however they wouldn’t provide the player on the ball with different options. Both stayed on the same horizontal lane, which made them quite easy to defend for the opposition. In addition, when the two midfielders stay on the same lane, they aren’t able to combine together.

After a couple of matches this problem was already fixed for the most part, with the positioning of the midfielders improving almost every game. Now when one of the central defenders has the ball and dribbles forward, the central midfielder on the side of the ball gets into a slightly higher position in order to create more space for the player on the ball. The far-6 than automatically becomes slightly lower than the ball-near 6. Allowing him to receive from the central defender on a diagonal angle, while also being able to receive the lay-off from the ball-near 6 in case he receives.

Lack of quality on through balls

In order to develop a build-up into an actual scoring chance, through balls have to be accurate. With Feyenoord, on numerous occasions during the first eight matches, there were opportunities to turn possession into actual goalscoring chances, hadn’t it been for a lack of quality on the through ball.

Often, the pass is way too hard, causing the ball to go out before the receiving player can get to it. This especially happens on the (right) side, when one of the players makes the run into the halfspace and the other run tries to play it into the open space.

Players stay on the ball too long

Feyenoord have this problem especially in the midfield area. Instead of playing everything within one or two touches, players stay on the ball too long. This causes the speed of the play to go down, allowing the opposition to get back into position and take out passing lanes that were initially open.

This also happens when the two central defenders dribble into the midfield at times. They are so focused on the vertical pass to the winger in the halfspace, that they are unable to recognise that it’s the fullback who has become the free player and wait so long that the opposition are able to shift to the side of the ball.

Players don’t have any options

This mainly happened during the first few matches this season. The player on the ball moves into the midfield, while no-one is making themselves available to receive the next pass. Or, the other players start to move too late and are therefore not in position at the moment the pass has to be played.

During later matches this problem hardly occurred in the fashion it did during the first couple of matches. The only issue relating to this that still arises is a lack of options between the lines for the central defenders, which prohibits them from finding players between the lines.

The ball isn’t played through the lines (or in behind) while the option to do so is present

I think this is one of the main issues coaches run into when trying to implement a new possession-based style of play. In the past, players have learned not to take too many risks, which causes them to be averse to play line breaking passes (which have a high risk of being intercepted).

However, when playing a possession-based style of play, a team at times attracts more risks when they don’t play these types of passes. As they don’t play forwards, they hardly create anything themselves and attract the pressure by the opponents.

Another problem Feyenoord have in this respect is that their first team squad is very small. Behind the first eleven players there are hardly any substitutes that are able to replace them on a similar level. With Feyenoord having to sell a lot of players and lacking financial resources to get adequate replacements. Therefore, their bench is usually made up by mostly youth academy players.

When these players have to start by replacing an injured first team player, it’s normal for them to a) not have the same qualities on the ball as the injured player and b) feel somewhat nervous due to a lack of experience on this level. Which causes them to be avoidant of playing line breaking passes, especially from the back.

For example, Senesi was injured against Go Ahead Eagles and had to be replaced by Wouter Burger (who has left Feyenoord since) and the game after by Ramon Hendriks. Both played somewhat decent games, but were hesitant to play line breaking passes, causing Feyenoord’s build-up over the left side to be quite stagnant.

Technical mistakes

Similarly, by not having played this type of football before, players often lack certain technical skills which are required to execute this at 100%. Mistakes that can often be noticed are a poor body orientation, players not being able to pass or receive with their weak foot, and players not turning with the ball while there is nobody pressing them.

In addition, certain players also have a poor first touch, which requires them to take an extra touch before being able to play on. As it takes longer for the player on the ball to execute the next action, the defenders have more time to be able to close down the player with the ball. Especially Pederson, the right fullback, often has trouble with his first touch.

Not recognizing the advantages

Due to their style of play, Feyenoord are often able to create a numerical advantage around the ball. However, due to their previous style of play, the players don’t always recognise these situations. Causing them to play forward too soon, or not progress even though they are able to.

Kökcu’s orientation

A common moderator for a lot of the other mistakes Feyenoord make in possession, is a lack of adequate orientation before receiving the ball. Which causes the receiving player to not recognise the situation (third man, or overload), and not see if he is being pressed or not (turning with the ball).

The reason I single out Kökcü is because he is Feyenoord’s main playmaker in the midfield area, therefore seeing him orientating himself is quite common and there is to be expected more of him than of Toornstra when receiving the ball.

What’s quite noticeable in these situations is that Kökcü looks around 2-3 times before asking for the ball, however once he asks for the ball, he doesn’t make a final check. This causes a lack of information on his part, as he doesn’t know what has changed in the last 1-2 seconds after he made himself available. Therefore, at times he is either too conservative as he doesn’t know he isn’t being pressed, and at times he does try to play forward while he is being pressed.

Creating chances

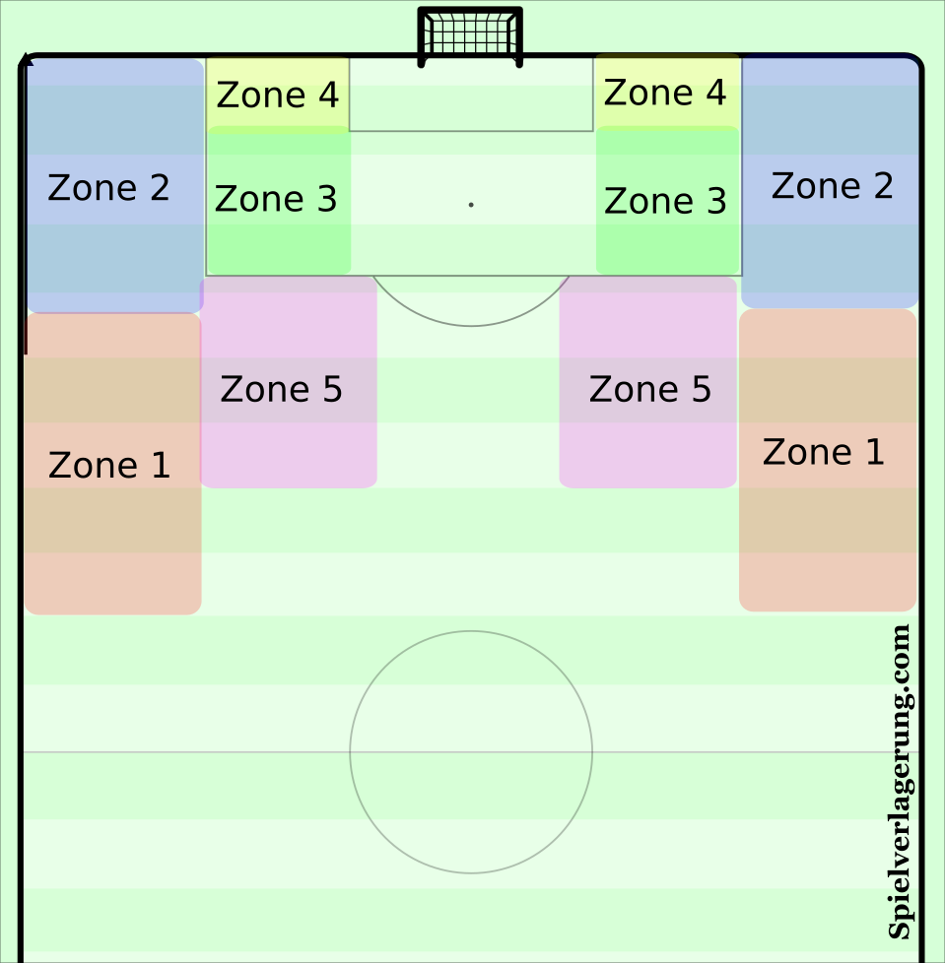

Before I’m able to explain how Feyenoord create chances through the left and right side, I think it’s important that I explain what different zones I distinguish to play crosses from.

Personally, I distinguish 5 crossing-zones from where crosses can be played. All of them with a different cross that’s ideal for that situation. Zones 1-4 were created by MBP School of Coaches in Barcelona, while I added the fifth myself.

The defenders are usually on the edge of the penalty area when the ball is in zone 1. Therefore, space opens up between the defenders and the goalkeeper. The ideal cross from this zone is then to play an early cross into the space between the defenders and the goalkeeper. Ideally the ball is played far enough from the goalkeeper that he is hesitant to come out of his goal, while the ball is played far enough from the defenders allowing the attackers to make the run into the space behind him.

Most teams put pressure on the ball with their fullback, when the ball is in zone 2. The near-sided centre back usually positions himself on the edge of the 5-meter line, in order to be able to deal with inaccurate crosses that come in. While the second centre back and the far-fullback usually man-mark an opponent. As the near-sided centre back isn’t marking a direct opponent, crosses towards that zone are very unlikely to become successful. Either the centre back intercepts it, or the goalkeeper is able to move out and catch it. Therefore, from zone 2 it’s best to play a high cross towards the far-post. This is the least covered area in this situation, and as the defenders on that side are often caught ball-watching, the chances for one of the attackers to get free of marking in that area are much higher.

In zone 3, players are already in the penalty area which means that distance the ball has to travel to a free teammate isn’t that big anymore. Therefore, from this zone it’s best to play a low cross to the open space. This open space can either be a low driven cross between the defenders and the goalkeeper, or a low cross to towards the penalty spot. The advantage of playing a low cross is that the receiving player has more control over the ball when receiving, and therefore a higher chance of converting the cross into a goal.

In zone 4 the player with the ball has made the movement towards the end line. The defenders usually drop back, in order to block potential crosses into the space just in front of the goal. Therefore, it’s the space around the penalty spot that usually opens up when a player in this zone. Thus, from zone 4 the ideal cross is to play a low cutback cross to the open space in front of the defenders.

Finally, we come to zone 5, the zone I added myself. When you are crossing from the halfspace, it’s best to play a high cross towards the far-halfspace. Usually, teams will leave space behind their defence. In addition, by playing it to the far-halfspace, the attackers attacking the box are able to exploit the blindside of the defenders who are usually looking at the ball when the cross comes in.

It’s important to note that these are guidelines, and not set in stone. Different crosses from these zones can also be effective, depending on the situation and reaction of the defenders.

Attacking over the right-side

Underlapping on the wing

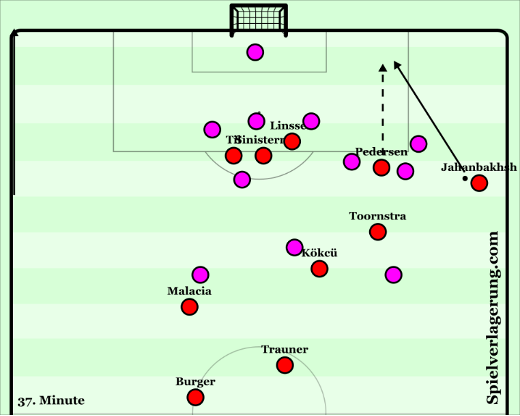

When Jahanbaksh or Pedersen has the ball in a wide area on the right-side, the other one will make an underlapping run through the halfspace. We see this time and time again, both in the midfield area, as well as when one of them is about to cross from the wing.

Pedersen’s crosses from zone 2

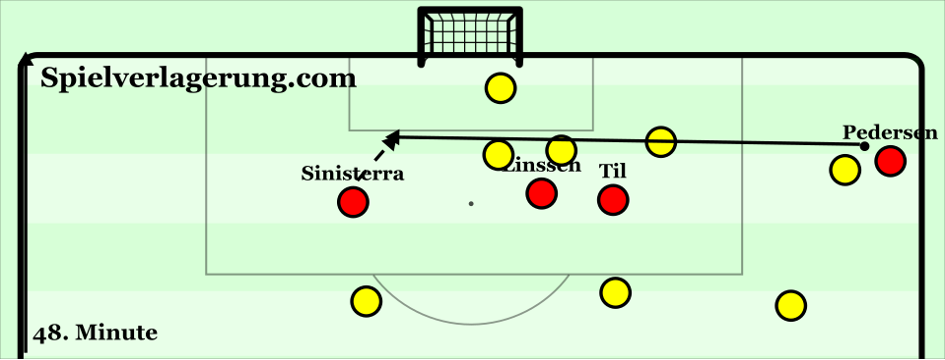

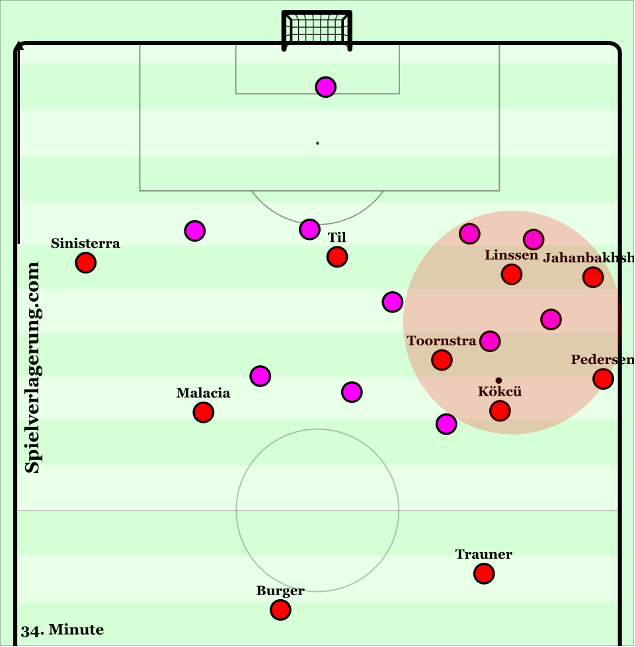

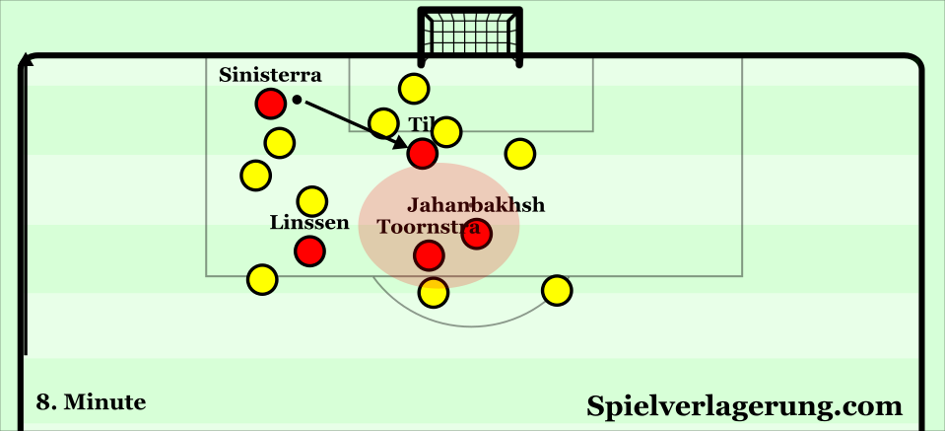

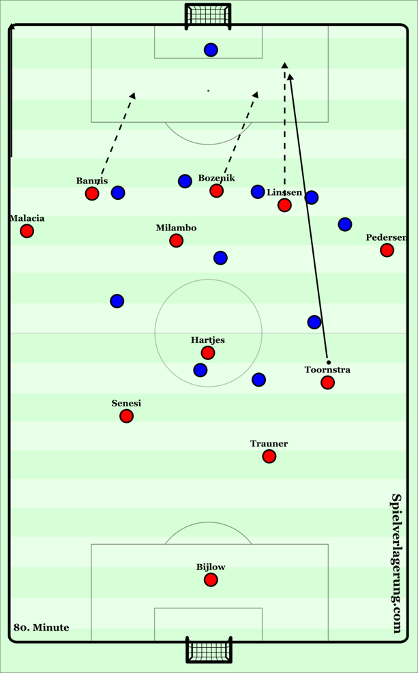

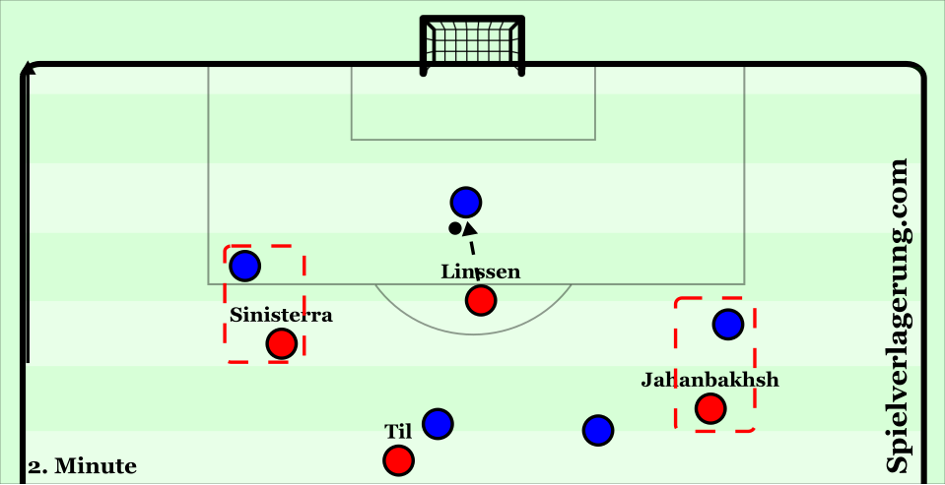

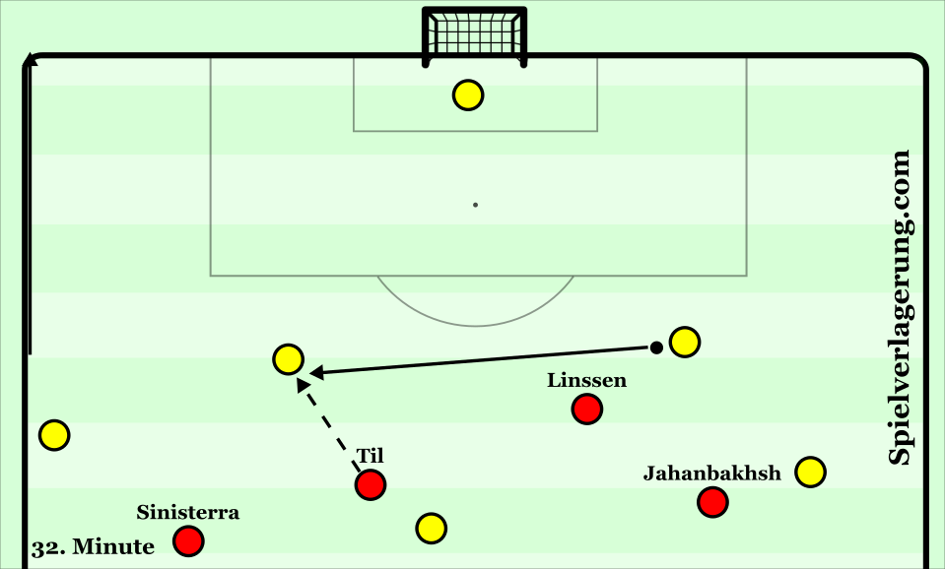

On the right side, a lot of crosses come from Pedersen while he is positioned in zone 2. In these instances, Feyenoord always have three players in front of the goal. Linssen, as the striker, makes the run towards the near post. Sinisterra, the far-winger, makes the run to the far post. And Til, as the attacking midfielder, attacks the space that opens up between the defenders.

As mentioned before, most teams look to have one of their centre backs on the 5-meter line, in order to intercept crosses. Therefore, Feyenoord are often able to create 3v2 situations against the remaining centre back and fullback.

The centre back usually goes with Linssen towards the near post. Leaving the fullback to take care of both Sinisterra and Til. When he stays with Sinisterra, this leaves Til free to attack the open space. While moving towards Til leaves Sinisterra free at the far post. In addition, Jahanbakhsh usually makes the run through the halfspace during these instances, as mentioned before.

The reason Til is able to get free in so many instances, or force the defenders into making decisions, is his very clever positioning just before the cross is played. Most teams would want one of their midfielders tracking Til’s run when he enters the box, to ensure all players are marked. However, Til usually attacks the penalty area from the far-halfspace, making it hard for the opposition’s midfielders to focus on his movement while also focusing on the ball. In addition, Til takes up very cleaver positions between the lines. Ensuring he is just far away enough from both the defenders and the midfielders so that neither is really able to pick him up. Often, we see him casually jogging while the play is developing and just when the cross is about to be played he makes a full sprint towards the open space, which makes it very hard for the opposition’s midfielders to track him.

In addition to the players in front of the goal, Kökcü and Malacia usually join the attack in a second wave in order to win the second ball. Malacia usually positions himself on the edge of the penalty area on the opposite side, while Kökcü makes the run to the central spaces.

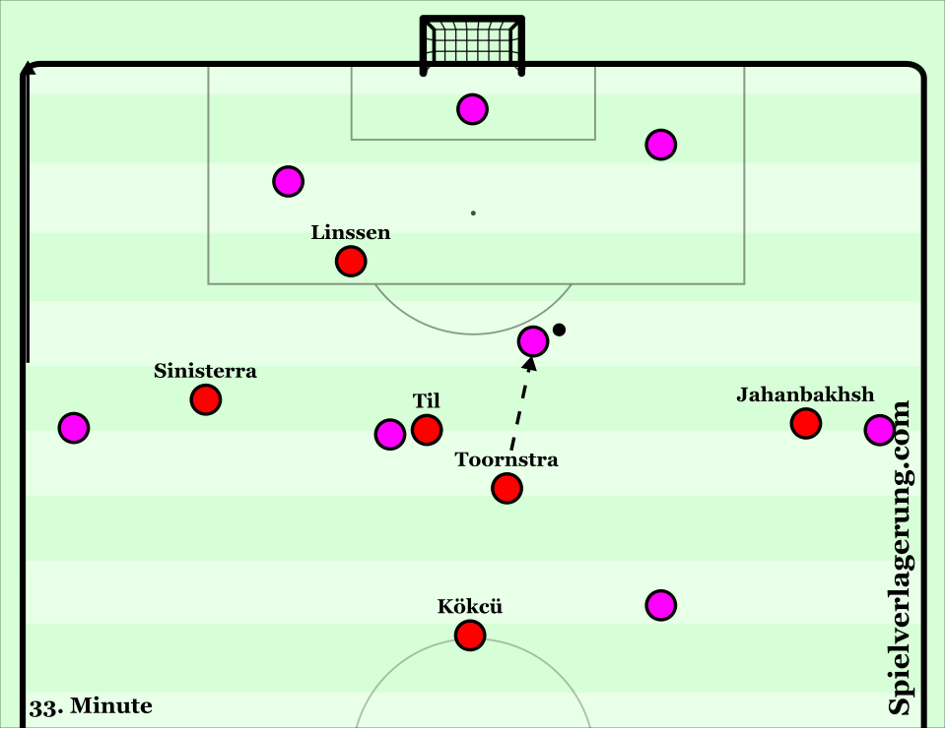

Toornstra’s crosses from zone 5

When the ball is on the rightside, Toornstra will usually position himself in the right halfspace. When the ball is played back to him, he usually looks to play the crosses towards the far-halfspace.

From this zone, the same three players will attack the spaces in front of the goal. Toornstra’s crosses are usually aimed to Til, who again attacks the open space between the defenders from the far-halfspace.

Problems when attacking over the right-side

The main problem Feyenoord encounter when attacking on the right side is that the cross being played into the box is not ideal. Pedersen has a lot of trouble with playing accurate crosses, however this has increased throughout the matches he played. One of the main problems which both Feyenoord and Pedersen still run into is the situation in which he is being pressed from a diagonal angle (mainly in zone 1). Pedersen isn’t able to play crosses around the defender, therefore his crosses from zone 1 are often misplaced. In addition, Pedersen isn’t a very technical player and isn’t able to beat the defender in a 1v1 apart from using his speed. Oftentimes Pedersen will have the opportunity to play an early cross into the space between the defenders and goalkeeper but refrain from it, trying to beat the defender and cross from zone 2. As he isn’t able to shake the defender, he either plays an inaccurate cross from zone 2, or plays the ball back missing a crossing opportunity.

Attacking over the left-side

Whereas Feyenoord have two right footed players on the right side with Pedersen and Jahanbakhsh, on the left they have a left footed fullback in Malacia with a right footed winger, Sinisterra. Already due to this slight difference, there are quite distinct differences in attacking over the right- and left side.

Sinisterra dribbles inside to look for the 1v1 and shoot

Throughout the first couple of games, Sinisterra has been very dangerous with his 1v1 skills. The Colombian winger often pulls inside to his stronger right foot in order to dribble at opponents and shoot at goal. He alternates between shooting in the near- and far-corner. Which has allowed him to set the goalkeeper on the wrong foot more than once.

In these instances, Malacia usually makes the overlapping run on the outside, often creating a 2v2 situation on the wing. If the ball is played to Malacia, the fullback either crosses from zone 2 or 3, or retains possession. As Malacia is a more technically gifted player compared to Pedersen on the right, it’s easier for Malacia to stay on the ball in these spaces in case there aren’t any decent opportunities to cross to.

Sinisterra passes the defender on the outside and crosses from zone 4

When Sinisterra is not able to pass the defender on the inside to shoot, he tries to get past the defender on the outside. In these instances, he will try to dribble towards the end line and end up in zone 4. From this position, Sinisterra looks to play a cutback cross towards the penalty spot with his left foot.

The positioning in front of goal is similar to crosses from the right side, with Linssen, Til and Jahanbakhsh all in the penalty box. Generally, it is either Til or Jahanbakhsh who makes himself available to receive the cross from Sinisterra.

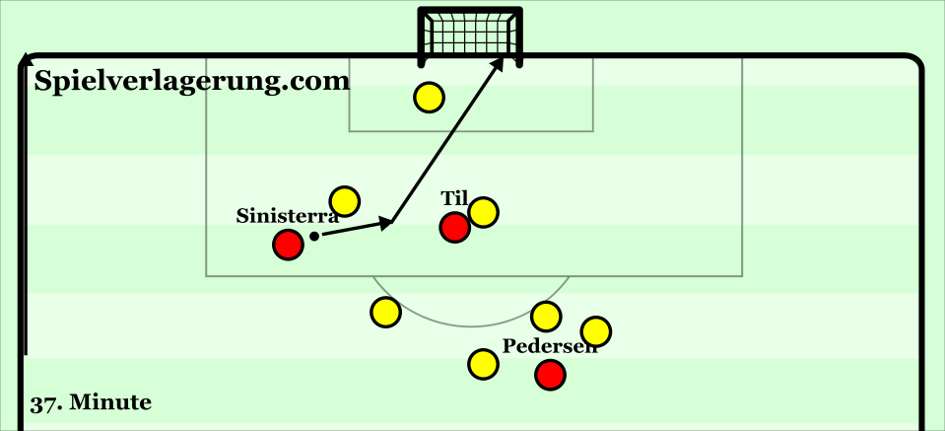

Senesi crosses from zone 5

Not a pattern we see often, however it still has been used (successfully) throughout different matches. When Senesi, the left footed left centre back, has the space to dribble forwards into midfield, he will look to play an early cross towards the far-halfspace similarly to the crosses from Toornstra on the other side, however usually from lower positions.

In these instances, it is again Guus Til who is the receiver from most of these crosses, as he looks to attack the space at the far-post.

Problems with attacking over the left side

The main issue Feyenoord run into when attacking over the left side, is when the players aren’t able to beat their direct opponent. As Sinisterra often tries to dribble inside and shoot, or outside and cross, the instances in which he isn’t able to beat his direct opponent leads to issues with creating actual scoring chances. Similarly, Malacia at times isn’t able to find space to cross from. Resulting in Sinisterra and Malacia having to combine together to recirculate, at times with Kökcü joining the pair to help out.

Another point of critique you could give to the leftwing players is that there are occasionally in 2v2 situations with the opposition’s winger and fullback. Despite both having very good technical qualities, they don’t always exploit these types of situations.

Attacking through the centre

Making runs in behind

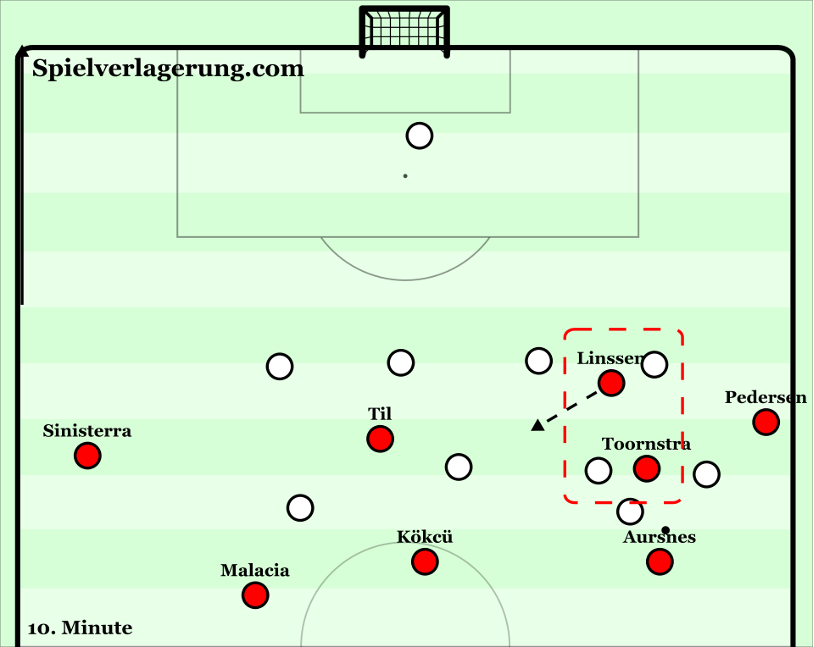

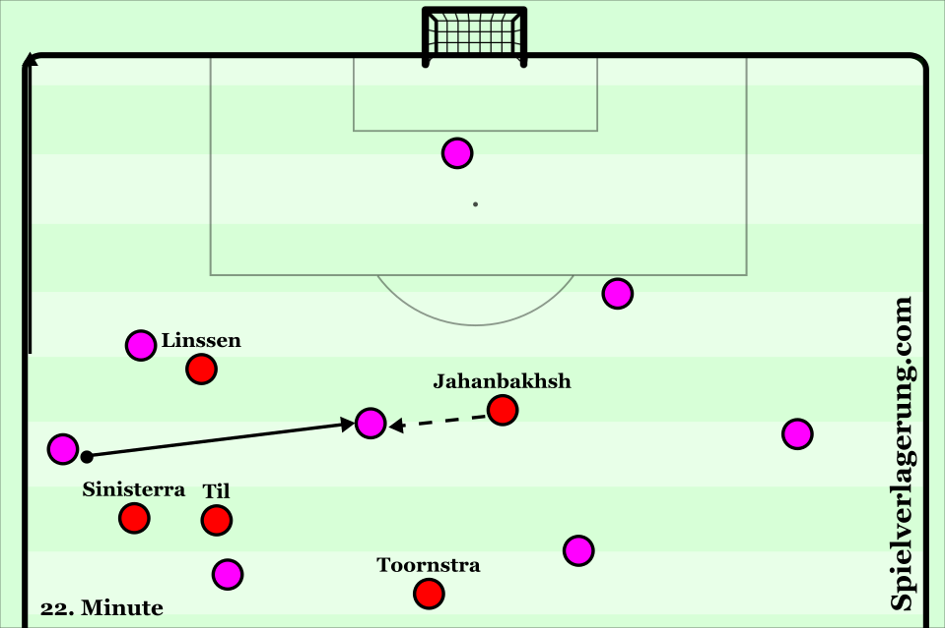

As mentioned before, Arne Slot is a big advocate in making runs in behind the defence. Which makes this one of the main ways Feyenoord attacks through central spaces.

In an amazing Dutch coaching magazine called ‘De Voetbaltrainer’ (which I just happen to work for), Slot laid out his tactics while managing Cambuur and described how he wanted players to make the run.

The player who makes the run should have a run-up from a couple of meters, to ensure he is able to gain momentum without running into an offside position. In addition, the run-up allows the player on the ball to spot the run from his teammate. The player should start running when his teammate on the ball has time and space and is controlling the ball. The player making the run should always make the run from the far-side, to ensure he isn’t running into the field of vision of the defender.

The pass should be given when the runner crosses the offside line. When there isn’t all that much space behind the defence, the pass should be precise. If there is more space to exploit, the pass can also be played into space. Generally, it’s best to play passes in behind a bit too hard than too soft.

According to Slot, runs should be made when: there is no pressure on the ball and the runner is at a reasonable distance; when the ball is in the halfspace, there should always be a run from the far-halfspace; when the ball is in the ‘hotzone’ (space between the lines) at least two players should make the run in behind; and when the play is switched to the far-side, the fullback should make the overlapping run to provide depth.

Linssen makes himself available as a central option

In the centre, it is usually Linssen who makes himself available as an option. He usually starts his movement from just behind the defenders, and makes the run towards the side of the ball. He does seem to favor moving to the right side over the left, as this is likely influenced by Til’s presence on the left side.

When Linssen receives after moving towards one of the sides, he helps the team to combine in these spaces. When he receives in a central area of the pitch, he usually looks to switch the play to the far-side.

Problems with attacking through the centre

The main reason that Linssen is now quite absent in Feyenoord’s build-up is the fact that his teammates are very reluctant to play the line breaking passes to him. Especially in the game against Willem II, this was very noticeable. Linssen is making himself more available throughout the games, however time and time again the players in the midfield area prioritise different options.

Another problem of which Linssen himself is guilty, happens when he makes himself available on the right side. Linssen has the habit of moving into the same line as a midfield player and thereby not being an option for the player on the ball.

When the midfielder makes himself available as well, Linssen should take up a more central position in order to open up a different passing lane.

Lastly, as Linssen is a winger turned striker and not a ‘real’ striker, he doesn’t always recognise situations in which the striker has to make the run. We can see this happening whenever there is an imbalance in the last line of the opposition. Normally, the striker makes the run to exploit this imbalance, either getting free or dragging a defender with him and opening up the central spaces. However, at Feyenoord this isn’t always the case. With Linssen often staying in a central position and not exploiting the imbalances.

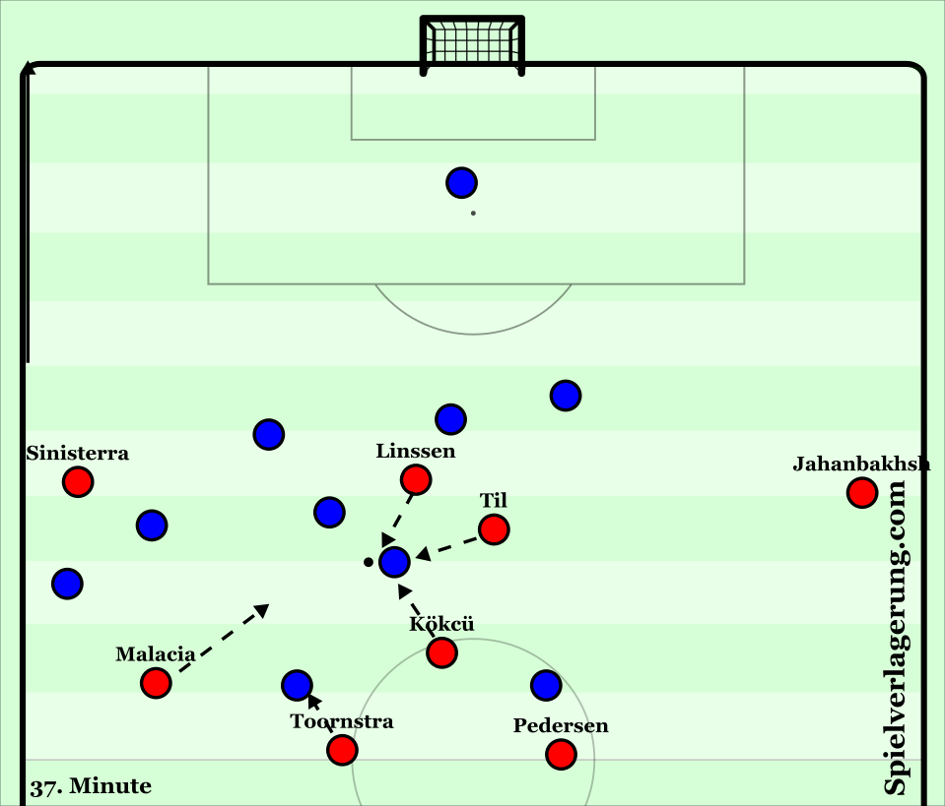

Transition from attack to defence

Feyenoord look to immediately counterpress upon losing the ball. With their possession-based approach, the transition from attack to defence plays in important role in their overall dominance during matches. Is the negative transition inadequate, than the opposition are able to break out and exploit Feyenoord’s high positions every time Feyenoord lose the ball. Is the negative transition organised well, than Feyenoord is able to lock the opposition up in their own half.

Feyenoord’s counterpressing is a mixture of space- and man-orientated. Usually, the initial pressing is more space-orientated, while the pressing becomes more man-orientated when the ball is being forced into a certain zone.

Feyenoord’s counterpressing is especially effective when they are able to force the ball towards one of the wings. With the sideline limiting the options for the player on the ball, Feyenoord are often able to mark all the near options and force the opposition into a turnover.

One major asset of Feyenoord are their two central defenders, Trauner and Senesi, who are very strong defensively and are very comfortable with moving into midfield to win their duals. During the counterpressing they often move up as well, in order to prohibit one of the forwards to receive between the lines. In addition, especially Trauner is really good in reading passes and intercepting them before they reach the desired opponent. In this way he has more than once been able to intercept a through ball to a player going 1v1 with Bijlow.

When Feyenoord lose the ball in their own half, the last line drops back usually with either Toornstra or Kökcü pressing towards the ball. The other players go into a full sprint to get back behind the ball as fast as they can.

On set-pieces it is often Pedersen who stays back. Being the fastest of the four defenders, Pedersen is often able to track back attackers after Feyenoord lose the ball and the opposition are able to counterattack.

Problems during the negative transition

Even though Feyenoord are quite successful implementing this style, they run into similar problems as most teams who start applying aggressive counterpressing.

The organisation upon losing the ball isn’t sufficient to counterpress

Personally, I think this is the most common problem for teams that start counterpressing. The negative transition already starts when the team is in possession. If the distances between the players are too big, it’s very hard to directly press the ball upon losing it.

Also, with Feyenoord we see this happening from time to time. Either the distances to the opponents in their area around the ball are too big, or none of the players is in a position that allows him to immediately press the ball.

The player who presses is outplayed too easily

Another common problem among teams that start counterpressing. The first defender sprints towards the ball in order to apply pressure. However, he doesn’t stop in time and is therefore outplayed rather easily. Meanwhile, all his teammates have anticipated on his pressing, which causes gaps when the initial pressing player is outplayed, causing the opposition to be able to play balls in behind.

Not enough pressure on the ball

The difference with this category compared to the first one, is that with the first one I referred to players not being in a position to press and with this one the players are in position, however the player nearest to the ball gives too much space to the player on the ball.

Similar as to players being outplayed rather easily during the counterpressing, this results in the opposition being able to play a through ball while Feyenoord’s defenders are anticipating on the counterpressing by moving forward.

There is pressure on the player with the ball, but his passing options aren’t being marked

In other instances, the initial player is able to press the ball but the direct passing options aren’t being marked. This allows the opposition to get out of the counterpressing rather easily.

This category usually has one of two causes. Either the players are too focused on the ball, and don’t realise they have to mark an opponent. Or, the near-players do react to the loss of possession and counterpress, but the players further away don’t react and therefore don’t close of the spaces around the ball.

Feyenoord’s fullback moves away too early

As mentioned before, Feyenoord’s far-fullback move towards the halfspace when play is developing over the other side, in order to cover the opposition’s far-winger. When play is moved back to the centre, they move away from the opposition’s player in order to become available as a passing option themselves.

At times, especially in the final third, Feyenoord’s fullback starts moving away from the opposition’s winger as he anticipates on a switch of play. However, at that moment possession is lost by the player on the ball. Which causes the far-winger of the opposition to be free.

A benefit in these instances for Feyenoord is that both Malacia and Pedersen are rather quick, and often able to overtake the opponent when sprinting back.

Defensively

High pressing

Feyenoord have turned into an aggressive high pressing side under Slot. The team looks to press high up whenever possible in order to win the ball back as soon as possible.

General patterns

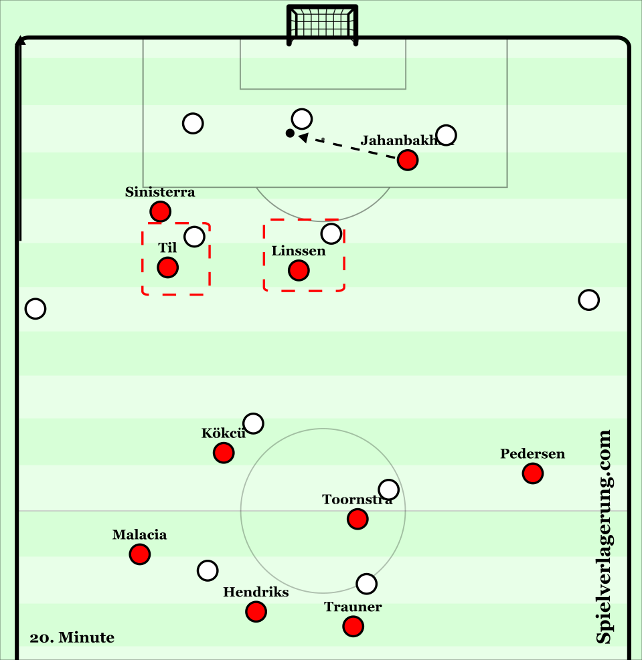

On a goal kick, Linssen presses the centre back on the ball, while taking out the passing lane to the other centre back. Often Linssen will start somewhat to the right of the middle, in order to force the ball to the right centre back. With Sinisterra taking up a position between the centre-back and fullback on that side. Til covers the ‘6’ on the side of the ball, with the far-winger moving inside to cover the far-6. I think Feyenoord want to force the build-up over that side, as Jahanbakhsh is better at moving inside to cover the far-6 than Sinisterra is. While Malacia on the left is a better defender than Pedersen is on the right.

Especially the tucking in of the far-winger to cover the far-6 has been a major improvement in Feyenoord’s pressing over the recent matches. During the first couple of matches this season, the wingers would remain wide, allowing the opposition to overload the centre. Feyenoord still often run into issues regarding this aspect, as discussed later, but the improvement of their pressing is definitely noticeable.

In case the ball is switched to the other side and Til isn’t able to mark the near-6 in time, or the far-winger isn’t able to move inside in time, one of Feyenoord’s central midfielders moves up. This leaves space in the midfield area but ensures the opposition isn’t able to generate a free player in their build-up.

Pressing the goalkeeper

During open play Feyenoord will often look to press the goalkeeper when he receives. In those instances, Linssen is the one to press the goalkeeper directly. Sinisterra and Jahanbakhsh move up to cover the central defenders.

When the goalkeeper in these instances is able to play the ball to one of the fullbacks, Kökcü or Toornstra moves out.

Trauner is a beast

Whenever Feyenoord manage to force the opposition into playing a long ball, it is (almost) always Trauner who goes to win the header at the back. Trauner is very strong in the air and (almost) always wins these types of duels.

The other defenders form a diamond like formation, with Senesi dropping behind Trauner, and Pedersen and Malacia moving inside a bit.

Opposition reaches the fullback

In case Feyenoord’s initial press is beaten, and the opposition are able to switch the play and reach the far-fullback, Toornstra or Kökcü will move out to the side and try to delay the progression of the fullback. The other plays than sprint back in order to get back behind the ball again.

Alternative shapes

Slot has switched the pressing style on some occasions in order to facilitate the pressing better.

In some games, Feyenoord have gone to a 4-4-2 pressing with Til pressing one of the centre backs while keeping the defensive midfielder in his covershadow. One the one hand, this allows for more pressure on the ball (which is the reason it has been used at times). On the other hand, Feyenoord have trouble with defending the ‘free’ midfielder once he receives as the spaces between the midfield and attacking line are rather big.

In the game against Utrecht, Feyenoord had to switch their defensive style completely as they couldn’t deal with Utrecht’s 3-box-3 formation. Therefore, during the first half, Slot switched to a 4-2-2-2 type of pressing with Linssen and Til marking the two ‘6’s’ and Jahanbakhsh and Sinisterra pressing the two central defenders.

Problems during high pressing

Far-6 not covered

One of Feyenoord’s main problems during pressing. During the first couple of matches this mainly had to do with the wingers not realising their role when the ball went to the other side. In more recent matches, it has more to do with the opposition finding ways to manipulate Feyenoord’s pressing. As Jahanbakhsh is in a split-position on the right (between the far-6 and the fullback), his job can be made increasingly difficult by increasing the distance between the players. As the fullback moves up and out wide, at times the distance to the far-6 becomes too big to cover, which allows him to get free.

Another issue Feyenoord have in this respect is when the opposition builds-up over their left side and then switches it to their right side. When the opposition builds up over the left it becomes Sinisterra’s role to move inside and cover the far-6. However, Sinisterra often misses the moments he has to move inside and therefore the far-6 is often able to get free unless one of the midfielders moves up.

Linssen isn’t able to put pressure on the ball

As Linssen has to make the curved run from the far-side, he has to cover quite some distance before he’s able to press the ball. At times, this means he is too late to put the player with the ball under pressure. When this happens the opposition is usually able to switch the play to the far-fullback, who is free as Jahanbakhsh has just moved inside to cover the ‘6’.

In addition, Linssen had some trouble with central defenders who made a feint before going backwards and passing to the other centre back. In the game against Luzern Linssen is outplayed multiple times in this way. He does seem to have improved in this aspect. Against Willem II, for example, the central defenders tried to do something similar which caused them to lose the ball to Linssen and allowing Feyenoord to score.

The space in front of the fullbacks

Due to Feyenoord’s organisation, with the wingers defending high and often having to move inside, the space in front of Feyenoord’s fullbacks is often open. Especially when the opposition’s wingers drop slightly, Feyenoord’s fullbacks have to move out in order to press them which would leave space behind them.

In addition, with Malacia not being the tallest of the bunch (he’s just 1.69m), some opponents look to directly target the space in front of him as he has trouble with winning aerial duels. Especially Willem II tried to exploit this by having their goalkeeper constantly play long balls towards the space just in front of Malacia.

The central midfielders are outplayed or don’t recognize the situation

At times Toornstra and Kökcü, Feyenoord’s second line of pressing, are too late to move or lose their duels. This happens in a number of different situations.

At times, one of them has to move out to delay the fullback in his progression, but they arrive too late and are outplayed. Causing even more problems for the defenders, who are now down 5 players.

At other times, Linssen and the wingers move up to press the goalkeeper and the central defenders, but Kökcü or Toornstra doesn’t move up to cover the central midfielder, who then becomes free.

Lastly, when the opposition play a long ball, and Trauner isn’t able to get to the header, it is often Kökcü who has to jump to the occasion. However, he often loses this type of duel, as he is not the tallest, nor the best header of the bunch.

Midblock

General pattern

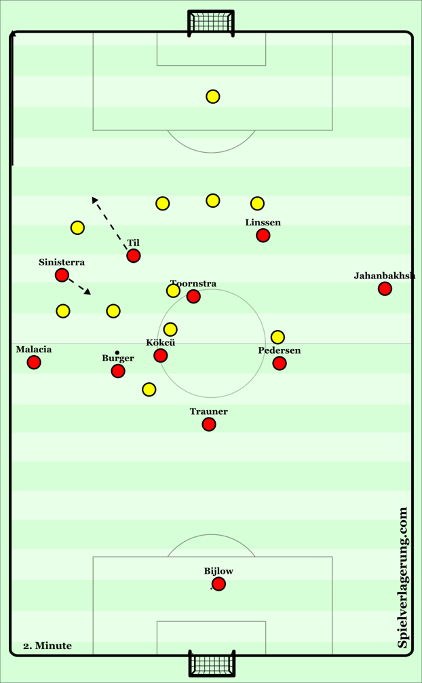

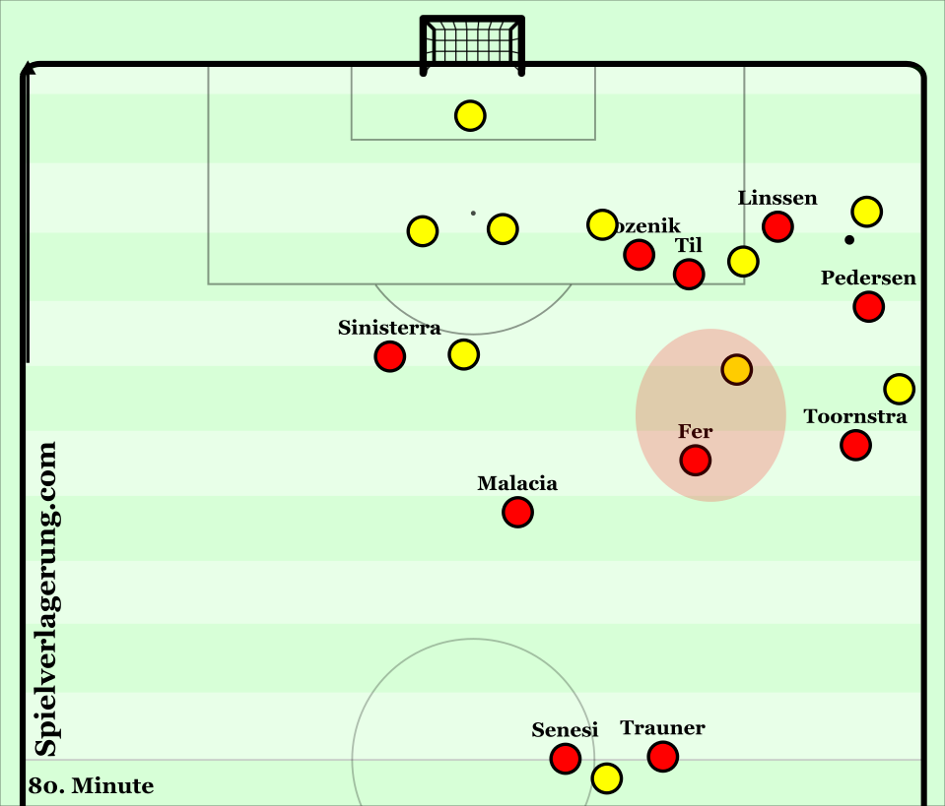

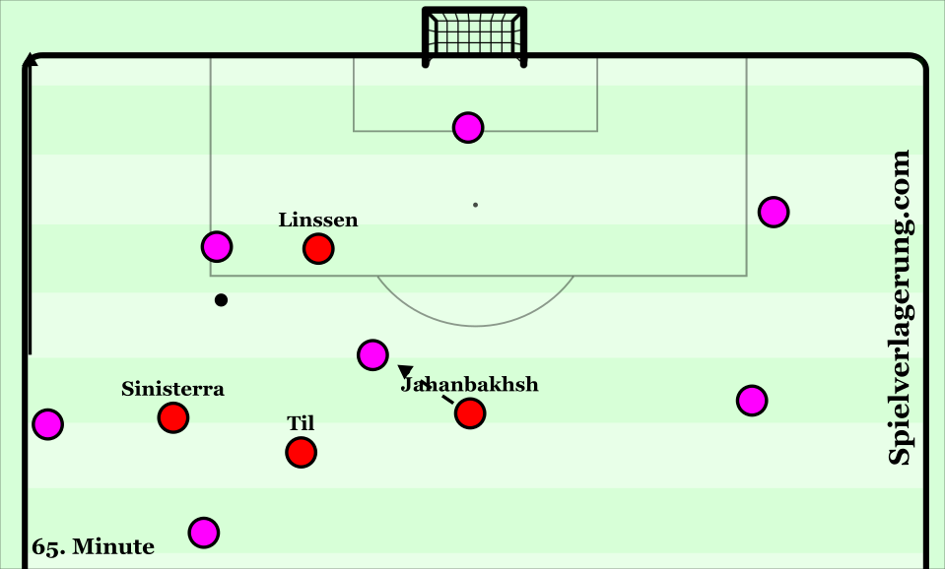

In a midblock, Feyenoord switch to a zonal 4-4-2 system. Til starts to play next to Linssen and the two strikers look to screen the passes to the opposition’s ‘6’s’.

Usually, the far-winger stays in a somewhat higher position in order to be able to press the far-centre back when necessary, while also being a direct outlet during the positive transition. Though this does cause a large gap between the far-central midfielder and the far-winger at times. Allowing the opponents to switch the play rather easily, once a player in the centre of the pitch has been reached.

A pass to the fullback is the main pressing trigger Feyenoord use in this situation. In those instances, the winger moves out to press the fullback, with Linssen immediately moving forwards to press the near-side centre back.

Problems when defending in a mid-block

Trouble with staying in the zone

As Advocaat played a full-on man-marking style last year, it was to be expected that Feyenoord would run into some issues regarding their zonal defence. Especially during their first few matches there were some ‘beginners’ issues’ with this new style of defense. One of them being the two central midfielders tracking a direct opponent for too long, and therefore opening up the central spaces in front of the centre backs. In later matches Toornstra and Kökcü are keeping the zone much better.

A similar issue is when Linssen and Til do not take out the passing lanes to the central midfielders correctly. In those instances, Feyenoord’s midfielders have to move up in order to mark the free midfielders. Which causes the space behind the midfielders to open up.

Space between the lines is too big

Not a problem specific for zonal defences, but still one that often occurs. The problem often starts with either the forwards moving up too fast, or the last line not moving up in synchronization with the ball.

In those instances, Feyenoord end-up in a 4-2-4 kinda structure with pretty big spaces in front of the fullbacks. Allowing either a dropping winger or a ‘6’ moving to the wing to get free.

Individual mistakes

In the midfield line, Sinisterra is defensively the obvious weakpoint. His positioning often isn’t ideal (being too high in relation to the opposition’s fullback) and he’s often beaten during 1v1 situations as he is too aggressive in his pressing.

In the last line, the weak point seems to be Pedersen. The right fullback is able to compensate a lot for with his speed, but his positioning is often off. He has more than once been beaten by an inside pass between him and the centre back. While he also has trouble with defending switches of play towards his side. Often allowing the opponent to receive before being able to pressure him.

Low block

General pattern

Feyenoord’s low block isn’t all that spectacular. The defenders cover the space in front of the goal with the two central midfielders covering the space at the height of the penalty area for the near-post and the centre.

Also, the attackers often all drop back to get into positions behind the ball. In these instances, Feyenoord have a very compact block around their own penalty box.

What I did want to mention though are some problems Feyenoord have in their low block.

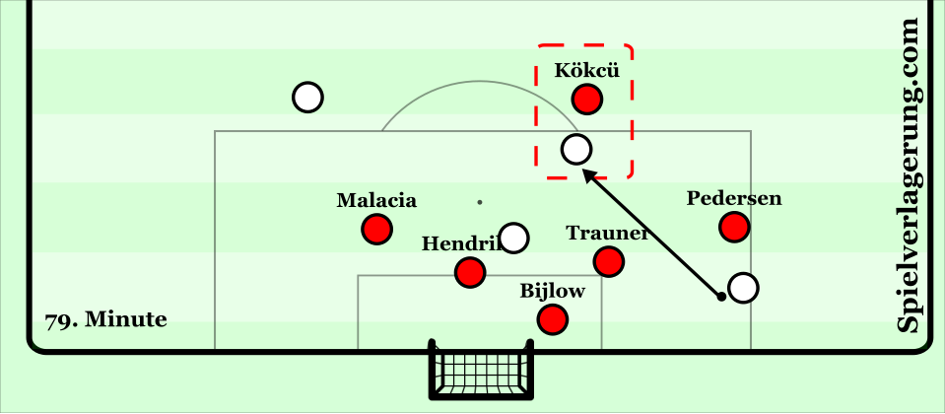

Kökcü doesn’t track runners into the penaltybox

Also happens with other midfielders, but I found it mainly prevalent for Kökcü. Whenever one of the opponent’s midfielders makes a run into the box, he often isn’t tracked by Feyenoord’s midfielders. This allows the opposition’s player to arrive freely in the box and potentially score.

Senesi loses his man

With Senesi being one of the better defenders Feyenoord have had in years, I was quite surprised to see this. Nonetheless, when examining Feyenoord defending in a low block it is often noticeable that the central defenders are too ball-orientated, and especially Senesi, starts moving towards the ball. In your own penalty box, the defenders should stay really tight on the opposition’s attackers, not allowing them to gain an inch. With Feyenoord we can more than once see attackers get free, as the defenders start to move towards the ball and lose track of their opponent.

Transition from defence to attack

Turnover in the final third

When Feyenoord win the ball in the final third, they usually look to shoot at goal as quickly as possible. Especially Toornstra is often seen shooting from a second line position towards goal, after winning the ball in a high position.

In other situations, for example when Feyenoord win the ball from a centre back during pressing, the player who won the ball passes to a player in a better position to shoot at goal.

The upside for Feyenoord with this type of play is that they are able to turn turnovers into scoring chances. The downside is that the quality of those scoring chances is generally quite low, as shots from outside the penalty box have a low probability of resulting in a goal.

Turnover in the middle third

When Feyenoord win the ball back in the middle third, they look to immediately play the ball forward and set-up a counter attack. Usually, it are the four forward players (Linssen, Til, Sinisterra and Jahanbakhsh) who join in these counterattacks. Kökcü and Malacia are the players who join in the second wave of the counter.

Within these counterattacks, Feyenoord look to start the counterattack one on side before switching it to the other side to get someone into a 1v1 situation.

However, when Feyenoord win it around the halfway line with no direct forward options, or when the team is out of shape, the ball is played back to Bijlow in order for Feyenoord to be able to build from the back again.

Feyenoord do run into some issues when trying to play out these counterattacks.

First of all, Feyenoord have trouble with getting the ball out of the pressing zone, especially when the opponents apply direct counterpressing. This causes the opponents to keep direct pressure on the ball, which makes it difficult for Feyenoord to play a through ball.

In addition, other problems Feyenoord often run into are the through ball not being adequate (similar to the problem they encounter when building from the back), and waiting too long with switching the play which allows the opponent to get back into shape.

Lastly, Feyenoord’s attackers don’t always recognize imbalances. At times there’s space to exploit to make the run in behind the central defender, also in order to provide options for the player on the ball. These imbalances are missed at times, or the run is made but the player with the ball doesn’t recognize the opportunity.

Transition from their own third

When winning the ball back in their own third Feyenoord look to dribble forward and from there set-up the counter in a similar way as from the middle third.

However, Feyenoord have a lot of problems with transition from a low block. As all the forward players have dropped back to aid in the defence, Feyenoord don’t have any players left forward. This often causes the defenders who win the ball back to lack options and therefore they either a) lose the ball again or b) just shoot the ball away to allow the team to move up and defend from a midblock again.

Final note

In this piece I have focused on Feyenoord’s first matches until the first international break. Even though Feyenoord have gone on to develop their style of play, I tried to show though this piece the implementations Arne Slot has done to transform Feyenoord into a high-pressing and attacking side. In the article multiple issues that coaches will run into while making a similar progression with their teams have been addressed. I hope therefore that this piece will not only be for people who are interested in Feyenoord, but also for coaches who are preparing themselves for such a transition.

[ad_2]

Source link