NOVEMBER UNFOLDED IN a dream.

Duke went out to Las Vegas at the end of the month and beat Gonzaga. Coach K saw hints of greatness, as a young team arrived in a big game, in a big venue, and instead of being scared of the stage, it grew to fit and claim it. This flickering vision of what these Blue Devils might be, were capable of becoming, flashed bright and then would fade through the teeth of winter.

Coach K told his players his own hoops doxology: Every season is a lifetime.

“You get one shot at this,” he told his team.

Out in Vegas, Mike and Mickie saw their friend Elaine Wynn, the casino baron. They’ve known her since Duke beat her beloved UNLV in 1991 and she loved how respectful he was after the game, refusing to buy into the narrative that this was a battle of good versus bad. She’s been a great friend and a regular visitor to Cameron. Elaine loves how basketball for the Krzyzewskis is a family sport. She tells stories about going to games in Durham and seeing the three daughters lugging babies and diaper bags and bottles into the tight confines of the arena’s old wooden bleachers and wondered why in the world anyone would go to all this trouble to watch their dad and granddad work. Of course she gets it. “When you have a man that is so invested in a passion,” she says, “you either get on the train or you’re completely off the train and you won’t have a lot.”

Along with her ex-husband, Steve Wynn, she created some of the great Las Vegas properties, including the Bellagio. Once she ate there with the Krzyzewskis, after she no longer owned it, and little mistakes bothered her. She told Coach K that it took her a long time to understand it wasn’t her casino any longer. Then she smiled and said one day he’d have to deal with the same thing as he handed his program to someone else.

She visited Krzyzewski before the Gonzaga game, because the team always stays at the Wynn, but just briefly to say hello. He was there on business, she says. After the game, she went by the Duke hospitality room at the hotel and congratulated him on the win and hugged him goodbye. They made plans to catch up once all the madness ended. Krzyzewski loves Las Vegas. He plays video poker and visits the spa. He’ll sit in the sun. Then he and Mickie look at the shows in town, and research a great restaurant, and then make plans together. Since he doesn’t fish or golf or pursue any other hobby, a trip out west remains about his only distraction, a time for him and Mickie to be alone.

“He absolutely adores her,” Elaine says, “and she adores him. When they’re here they’re like teenagers. She’ll be watching him with a little glint in her eye. He’ll reach out and touch her arm.”

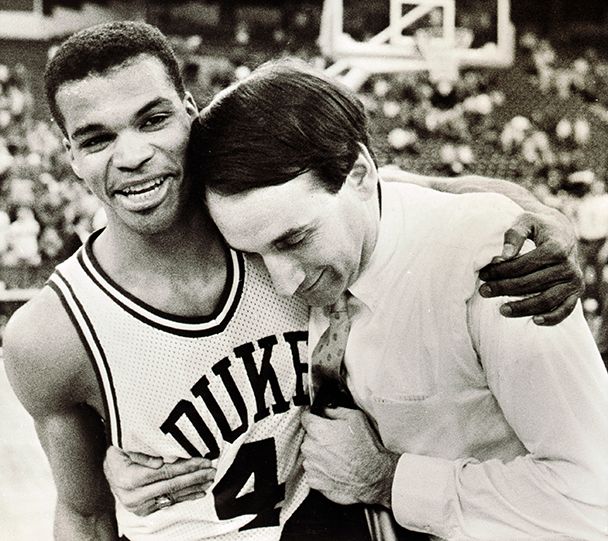

Coach K and the rest of the Duke basketball family have always embraced the job that Patrick Davidson did defending Chris Paul. Craig Jones/Getty Images

AFTER BEATING GONZAGA, the Blue Devils rose to No. 1. The top-ranked team in the country, they left on an early-evening flight from Raleigh into a cold Columbus, Ohio, on the next-to-last day of November. It was dark when they landed. The unranked Ohio State Buckeyes awaited. The Duke players were believing their hype, but the coaches weren’t. They worried this was a classic trap game, and they were right. On Nov. 30, Duke lost for the first time this season. Coach K looked at his players and demanded they learn from this feeling.

He’s lost 365 times in his career, each of them a small death, and there are four decades of his extreme reactions to them. You could pick any of them to get a sense of how his main coaching strategy seems to be setting himself on fire and hoping his team will be drawn to the light. Here’s one. In February 2005, as his team prepared to play Georgia Tech, Krzyzewski hit peak intensity. The night before the game, he played the team a battle scene from “Braveheart,” showing William Wallace lopping off heads and planting a sword in the ground. The following day, the team ran out for layups and then returned to the locker room. The Cameron crowd was booming. The assistants put on “Braveheart” again and as Wallace planted his sword, Krzyzewski came screaming into the room, waving his old Army saber. He planted his sword into a big planter of dirt an assistant had strategically placed.

“Let’s go, motherf—ers!” Krzyzewski yelled.

Nine minutes into the first half, during a timeout, Coach K screamed at the officials that Daniel Ewing had been fouled. Then he just collapsed. Mickie ran to the bench. The trainers rushed to his side. It was incredibly tense. Then he got himself up, gave his stunned players more instructions and kept coaching the game.

Four days later the Blue Devils beat No. 2 North Carolina. Then came two straight losses, one at Maryland and the next a stunner at Virginia Tech. The spiraling team rode a bus back through the night toward Durham.

“I remember it being quiet,” says Patrick Davidson, a walk-on guard for that 2004-05 team.

They got back late, or early actually, maybe 3 in the morning, and Krzyzewski called the team into the locker room for one of his infamous meetings. These would last, former Duke guard JJ Redick remembers, basically until one of the players started to cry. They finally went home around 5 a.m. When they got back for practice later that same day, they saw the board with the starters listed for the next game against Wake Forest at home, a team led by phenom guard Chris Paul. There were four names listed to start against Wake: two walk-ons and two former walk-ons.

“I don’t know who the fifth starter is,” Krzyzewski told them.

His plan, he said, was to go up in the stands and just watch like he didn’t know a single thing about the team. The assistants trotted out every brutal drill they could imagine — “nothing to do with basketball,” Redick remembers — like throwing a ball on the court and making two guys fight for it. They did boxout rebounding competitions. Five wind sprints, make a layup, then dive on the floor.

Redick won every drill. He always loved doing the gladiator thing. Coach told the team Redick and the four scrubs would start against Wake.

The next day the team roared onto the court. For the first three minutes, Davidson, who remains an object of cult obsession in the Duke world, pressed and mugged Paul, picking up two fouls and getting in the star’s head. When Krzyzewski finally took Davidson out to replace him with Ewing, he wrapped his arms around the walk-on in a huge bear-hug. Duke won.

Coach K would like nothing more than to end his final season with a sixth national title, and he sensed something special in this squad from the start. “I feel closer to this team than I have in the last decade,” he says. Michael Hickey/Getty Images

Five years ago, in January 2017, Coach K missed a series of games after midseason back surgery, a run of six procedures in 15 months. The person he seemed to punish most of all in his pursuit of excellence was himself, although all Duke players can tell you punishment runs downhill. The way Krzyzewski pushes himself has scarred him, to be certain, but it has also taken its toll on everyone who reached for greatness with him. While he recovered from his back operation, Jeff Capel ran the squad. The team lost at home against NC State. All the players got a mass text: Go to Coach K’s house immediately. They walked in to find three rows of five chairs set up. He went down the line, player by player. He told star Jayson Tatum, who recently relayed this story on Redick’s podcast, that all he cared about was the NBA and he should just quit officially, since he’d already quit in spirit. The players left and then got another text: Be in the locker room at 6 a.m. They walked in to find two trash bags by every locker. The assistants told them to take everything out of their lockers. Tatum carried his two trash bags to his car. When they returned for afternoon practice, the security code on the locker room had been changed. The players walked to the court to find a pile of white shirts and blue shorts. They hadn’t earned Duke gear.

Redick shivered when Tatum finished his story, and then laughed.

“There’s some PTSD there,” he said. “This is bringing back all the memories.”

THE DAY BEFORE the Ohio State loss, Father Francis Rog died. He was 91. Coach K got the news and flew home a few days later for the funeral. Moe met him at the private airport and got concerned when his friend limped toward the terminal door.

“What’s going on?” Moe asked.

“Ankle,” Krzyzewski said.

He didn’t look as energetic as he had beneath Madison Square Garden. Although he’d been saying something different in public, truth was, he had put a lot of pressure on himself, more than usual, to finish this last run the right way, to wring every moment from an experience he’d never have again.

“I want it to be so good,” he says.

It was taking its toll on Coach K and his family.

“I think they’re tired,” Moe says.

Moe and Mike rode together to the service. They arrived long before it began. Krzyzewski greeted old friends and then walked to the open casket. A man saw him coming and moved to give him space and for 30 seconds Coach K stood there and didn’t move. He walked away, and then walked back to the casket with his sister-in-law, Pat, who was married to his brother. Bill was enormous, 6-foot-5 and a barrel of a man, who retired a captain in the fire department and died only a few years later. He and Pat never got to realize all those plans they made about the life they would live once the last fire had been fought.

“My brother was my hero,” Krzyzewski says.

He moved around the sanctuary and shook hands and gave hugs. His presence seemed to comfort people. Eventually the crowd took its seats beneath the beautiful white marble and stained glass dome of the Polish basilica. The service began with a solitary ringing bell. Krzyzewski sat on the left side and didn’t speak. He said goodbye to his friend and counselor, the man who’d given him permission to become Coach K. Now in this winter of his career, all sorts of questions were following him wherever he went, about who he’d be when this ended, when he wasn’t Coach K any longer but just a wealthy, famous, respected grandfather named Mike.

Father Rog had always bridged those two parts of him, and now he was gone.

Eight men escorted his body from the church while Krzyzewski watched in silence, standing with a dark overcoat folded over his arms.

BY DECEMBER IT WAS clear those flashes of greatness against Kentucky and Gonzaga were, in fact, flashes. Coach K’s last team would have to be shaped in real time, while playing real games, starting conference play just before Christmas. ACC games meant the arrival of what he calls “battle mode.”

“He really believes battle mode is one of the reasons they win,” Bilas says.

Battle mode is a way of looking at the world, of ordering it, stripping away everything that doesn’t directly impact the next game. Visitors to town know not to be offended if all he can talk about is the team. There are lots of other signs. He’ll stop sleeping. He’ll skip meals. He’ll start to look gray. He’ll find fuel wherever he can.

“What amazes me is, despite all his success, his ability to keep a chip on his shoulder,” says Northwestern head coach Chris Collins, a former Duke player and assistant. “It’s amazing. The great ones have the ability to create their own adversity, their own enemies. We might have a mid-January game against Clemson. He’s coached 1,500 games, but he finds a way in those two days to get angry about something.”

Krzyzewski doesn’t know what he’ll do with this side of himself when the season ends. “I haven’t thought about that, but it’s interesting,” he says. “Part of having that keeps you young. Keeps you relevant. Keeps you purposeful. And so it will be interesting where I channel that. Because it’s got to be in something. If it goes, then you might as well say goodbye.”

The greatest enemy of battle mode is memory mode, and he stubbornly refused this season to engage in nostalgia. The team never heard him talk about his last dance. The truth is, he loves this spartan way of living and when his career is over, it might be what he misses the most. Mike Krzyzewski becomes Coach K in this ritualized world. Krzyzewski settled into long-ago defined patterns. Pizza (usually from a local place) waiting on the bus after every road game, which he eats in his usual seat, second row on the right side. When he walks onto a team plane, he doesn’t have to think: pass the players, who he has always put in first class, then to the left-side aisle seat in the first row of coach. It’s in these little rituals that memory mode lurked, and he started to consider the scarcity of the feeling he got walking onto the court at Cameron.

Coach K worked all ACC season with a furious joy. He rode his stationary bike, working up a full sweat, and watched film at the same time. The coaches gathered after every game to break it down together. For a 6 p.m. game, they’d usually be done at midnight. Now these film meetings happen at Cameron. For years they happened at Coach K’s house, where the assistants and Krzyzewski would order pizzas and watch tape all night. Several past assistants talk about throwing the morning paper on the porch as they left after sunrise. The pizzas were a vital part of the routine. Krzyzewski liked to put salt on his pizza and, before he had to monitor his health, there would always be a salt shaker on his seat in the bus after games, so he could doctor up those postgame pies. During this final season, two old Duke stalwarts, Quin Snyder and Wojciechowski, met up for lunch on the road. They both reached for the salt shaker at the same time and smiled.

Dogs have always been a part of the Krzyzewski family, but the death of a beloved yellow lab named Blue was a cruel way to start Coach K’s season of farewells. Courtesy of Duke

FOR CHRISTMAS HIS FAMILY gave him a present to unwrap. Inside he saw they’d picked out a new Labrador; they made the deposit, and the puppy would be born at the end of March. Always loyal, he wanted to make sure his family knew he wouldn’t ever forget Blue, or think he could simply be swapped out for another dog.

“I’m not replacing Blue,” he said firmly.

They smiled and said they understood. This would be a beautiful new relationship, not an attempt to recreate an old one. Christmas is always a huge deal in the Krzyzewski family. Mike got Mickie a ton of pairs of pink Nike sneakers. Mickie always gets everyone matching pajamas, and this year they were black and white flannel pattern. There’s a photo of all smiles in front of a towering tree. The children and grandchildren all spend the night at their house, a big lock-in. This year Coach K scheduled practice during the family-only time.

“You’ve ruined so many Christmases!” Mickie scolded him.

She runs a tight ship. They call her the Queen Mother. Coach laughed and reminded her that this would be the last Christmas he’d ever ruin.

It’s been more than five decades since Mike Krzyzewski graduated from West Point, but the friendships that he forged remain strong today. Courtesy Army West Point Athletics

ON JAN. 16, in between a win versus NC State and a loss at Florida State, Coach K got the news that another of his West Point classmates had died, the first to pass during his final season. Bob Hoffman was a decorated war hero and a grandfather. Mike was in Bob’s wedding, one of the guys holding a saber — the same kind of saber he’d later use to fire up his team. Those long, gray line days were distant indeed. Just after Bob died, his widow, Lorie, was walking through their neighborhood in Idaho when her phone rang. A call from Durham, North Carolina.

Krzyzewski told her how sorry he was, and they laughed and remembered the old, good times. Each of them bragged on their grandchildren and talked about their families.

“You can tell how much that phone call meant to my mom,” Bob’s daughter Carina Van Pelt tells me. “My mom heard from every single person in that class, either a call or a nice long letter. It was pretty amazing how close they are.”

Even 53 years removed from graduation, West Point still matters to Krzyzewski, because of his friendships forged in the shadow of the daily Vietnam casualty reports, and because of the way his college coach and first coaching boss, Knight, shaped his life, in ways good and bad.

A young Mike Krzyzewski idolized Knight, even as part of him probably hated him, in that way that ambitious people sometimes can’t tell the difference. The basketball press made the comparison all the time until Coach K bristled at that, both wanting his mentor’s approval and wanting to be seen as his own man. As he started his climb in the sport, Knight loomed large in his mind, especially in the early 1980s. “You could almost see the wheels turning,” Bilas says. “What would Knight do?”

Knight rooted for Krzyzewski, wearing a Duke button on his shirt at the 1986 Final Four. But when Coach K won his first national title in 1991 and then beat Indiana in the 1992 Final Four, the relationship changed. Coach Knight did a limp drive-by handshake after the game, and when Krzyzewski waited in a hall for a second chance after the Hoosiers’ news conference, according to Ian O’Connor’s new book, “Coach K,” Knight blew him off completely.

Then the letter happened.

It’s famous inside Duke basketball as a critical breaking point. After the game in ’92, Knight had a mutual friend from West Point deliver a blistering letter that Knight had written, threatening Krzyzewski with an end of their relationship, just venom pouring off the page, turning a perceived slight into a paranoid, angry screed. Knight had been into Krzyzewski’s family home for his father’s wake and now this? This fracture would grow and shrink in the coming years until finally the coaches simply stopped speaking, or rather Coach K gave up trying to be the bigger man. “I think that’s been a horrible chapter in his life,” Bilas says. “Knight should have been proud of him. He’s like a child whose father won’t acknowledge his success.”

After that 1992 win over Indiana, with a Michigan game looming in 48 hours for a second straight national championship, the Knight letter dominated the insular Duke ecosystem. Krzyzewski got back to his hotel suite in a fog, just totally devastated. Current Notre Dame head coach Brey, then an assistant, remembers how they were trying to work and Coach and his wife kept bringing up the letter, trying to make sense of their hurt. Finally Brey knew he needed to do something. He stood up and spoke simply.

“F— Bob Knight,” he said.

THE GAME AFTER Bob Hoffman died, Mike Krzyzewski took out one of his rosaries and said a prayer, dedicating that night’s contest to his friend. He does that every game he coaches. It’s his moment to be alone before the coming storm. On the road he’ll sit in his hotel room and at home, he steps into a private room in Cameron, just off the big space where he does his postgame news conferences. Once he gets settled, he’ll reach into his right pocket, where he keeps the rosary given to him by Father Rog, blessed by Pope John Paul II, and finds peace and perspective. In his other pocket he carries another rosary, the one that belonged to his mother. This season he dedicated several games to his mother and father and brother. Against Virginia, he dedicated it to Mickie’s family, because she grew up near Charlottesville. On his desk in his spartan downstairs office by the locker room, he keeps photographs of young kids he met over the years in hospitals who died, and a prayer card from one of his first players at Army. He carries these people with him, inside him. They are him. He is always communicating across planes of existence. This spiritual life, this desire to walk with spirits, is one of his greatest gifts and, when swirled together with his Polish tribal roots and his West Point education, lies at the heart of his success. He is, most of all, a collection of everyone he’s ever met. Every time you see him on television he’s got a rosary in each pocket, twin portals, a way of communicating with the people who walked this road with him but didn’t make it to the end. Who are being carried by him to the end.

After all these years, Coach K is still willing to go to bat for his players. Exhibit A: His response when Wendell Moore Jr. was fouled by Clemson’s David Collins. Dawson Powers/USA TODAY Sports

JANUARY ENDED AND Coach K looked terrible. He always does this time of year. “That’s how you know it’s February,” Debbie K says with a laugh. “It’s Groundhog Day, it’s President’s Day, Valentine’s Day, Coach looks like s—. It must be February.”

Duke entered its toughest stretch of the season, four games in eight days, five in 12. Those became coded mantras — 4-in-8, 5-in-12 — and the whole program hunkered in battle mode, like a warship that sounds general quarters and turns on red lights. Duke won the first game against Carolina — folks inside the program bristled that the Tar Heels didn’t honor Krzyzewski during the game — and then turned around and lost to Virginia, a well-coached team that gives Duke fits. That was the fourth loss of the season, the last three by a total of four points. Three days later, Duke star Wendell Moore Jr. streaked toward the basket, Clemson guard David Collins undercut him and Moore came crashing down. He writhed on the floor, and Coach K wheeled around to the Clemson bench and screamed, “What the f— are you doing?”

He started moving toward the baseline. Debbie screamed in front of her television and realized her father, a 75-year-old man, was stalking off to fight a college kid on national television.

“My dad has very small lips,” she says, laughing. “When there are no lips, he’s seething. I haven’t seen him that mad in a very, very long time.”

Debbie is sitting in her dad’s conference room talking about the play, and how Coach K got himself under control, and how the Clemson coach did a masterful job defusing, until everyone hugged and the game continued. His mentor might have detonated his career in a moment of rage, but Coach K isn’t his mentor.

“You say this Bobby Knight thing …” Debbie K says. “This is where …”

He’s coached 1,500 games, but he finds a way in those two days to get angry about something.

– Chris Collins

Her voice fades, and she’s quiet. Her dad carries the scars of a relationship soured by pettiness and anger. But he also didn’t replicate Knight’s mistakes. One of the most poignant parts of this season has been the constant stream of former players coming to meet Coach, bringing family members and children, wanting to be part of the end. He has spent his final season surrounded by the relationships he built over five decades, relationships that remain intact in no small part because he saw firsthand how not to treat someone. There have been rifts along the way, but the relationships always seemed to win out in the end. The people close to Krzyzewski understand that Knight’s worst impulses live in Coach K but he has managed to control them.

When I ask him about Knight, he sighs and says, “It’s complicated.”

Then he talks immediately about working to be a better person.

“I don’t know when but in the last decade, I said, I am not gonna have hate or resentment be part of what I do,” he says. “My mom would say that all the time. She would say, ‘Why let that in your heart?'”

He learned how to let go of hate and resentment. He learned by example. He learned by practice, by teaching. Knight once imagined he’d be carved in stone, on the mountaintop of his sport, and now he’s the fifth-winningest coach who destroyed everything he built. His biggest contribution to basketball might be showing Mike Krzyzewski how not to treat people, which has allowed Coach K to emerge from this brutal grind of 47 seasons with his life and friendships and family intact.

Debbie K grins.

She knows she shouldn’t say it, but … what the hell.

“Karma,” she blurts.

Jon Scheyer won a national championship playing for Mike Krzyzewski in 2010, joined his coaching staff in 2013, and never left. Jaylynn Nash/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

EVERY MORNING MICKIE KRZYZEWSKI sends out that day’s basketball schedule. It starts on a family text chain called “Basketball Freaks” but gets forwarded around the Duke basketball world. (This thread is not to be confused with “Starting Five,” the group chat of Coach K, Mickie and their three girls). In Basketball Freaks, she has carefully listed all the college games they might care about, along with the time and the channel, sorted by ACC, Ranked and Other.

JohnnyDawkins v Houston 9:00 209

Ore v BobbyHurley 9:00 206

ChrisCollins v Minn 4:00 610

This happens every day, tracking Amaker’s Harvard or Nate James’ Austin Peay or Jeff Capel’s Pitt Panthers (aka The Fighting Capels), and folks look forward to their daily updates. The Duke basketball office is, and always has been, a blend of Coach K, his team and his family. When the three Krzyzewski girls were young, they had crushes on dad’s players and now some of their own girls babysit for the assistant coaches. Snyder lounging around the house as a student watching college football has given way to Mark Williams and Jaylen Blakes learning how to play bocce ball in the backyard. The one time Debbie got busted drinking in high school, part of her punishment was her parents telling the team. She remembers Danny Ferry running into her and her mom and dad at a Duke football game and cracking, “Hey, Deb, wanna go get a few beers?” The lives of all these people are so intertwined that it’s difficult to tell where family ends and the team begins.

“I view him as a second father,” Collins says.

His players became part of his life. They hung out with his mom. They knew his brother. Amaker remembers a tour of West Point that Coach took him on when they were in New York recruiting. Brey remembers all those trips through Chicago, where they’d finish work and roll through the Polish neighborhood and find something to eat.

Every former player I called had stories about hearing from him when something went good or bad in their life. Collins tells me about a tough loss he suffered early in his time at Northwestern against Maryland. They’d been up 11 with four minutes to go and lost at the buzzer. The team got on a plane and flew to Chicago, and around 1:30 a.m., as he’s driving home, his phone rings. It was Coach K, “just talking me off the ledge.”

Arizona State coach Hurley says he struggles even now to treat Krzyzewski like a peer because he reveres him so much. Only two people in his phone have their numbers saved with just a single letter. His wife, Leslie, is programmed as L, and Coach is simply K. After Hurley was almost killed in a car wreck during his rookie season in the NBA, and he finally started to drift back into reality, around the second day, he found his parents and Coach K leaning over his bed. Same thing happened years later when Jay Williams almost died in a motorcycle crash. Krzyzewski was in the air in a private plane when he got the news. Moe says he made the pilots turn the plane toward Chicago. From the air, Krzyzewski called Moe and asked if he could pick him up at the airport. Moe drove them to the hospital and stayed in the car while the coach rushed inside. He got there in time to be one of the first faces Williams saw when he woke up. When Coach K got back in the car, he turned to his oldest friend with tears in his eyes and said, “Moe, it’s pretty bad.”

His greatest gift has always been not only his ability to create deep relationships, lifelong relationships, but his need for them. He loves and is loved back in return, existing at the center of a huge spinning wheel, of players, and coaches, at Duke and on the Olympic teams, his family both in Durham and Chicago. So it’s important to know that this last season, although hard, has been a happy time, with Formers returning and bringing their children back with them. One Sunday, Krzyzewski came into his office, visited the guys in the training room and then went to watch film. Debbie texted and told him to look in the gym. They’ve got a closed-circuit camera in Cameron that he can always access. When he turned on the feed, he saw two of his assistant coaches with their kids, and two former players with their kids, everyone having a great time.

“It looks like a daycare center,” he says beaming.

Tommy Amaker was a member of Mike Krzyzewski’s staff for two national championships at Duke before leaving for Seton Hall, Michigan and then Harvard. Courtesy Duke

COACH K TURNED 75 during that brutal run of games, and he celebrated by going into the office on a Sunday. He’s been sleeping four or five hours a night, battle mode forever. “He looks horrible,” Bilas says. “He’s burning the candle at both ends. He’s overworking himself. He’s watching film all night, doing stuff he did when he was 40.”

The last game of 5-in-12 landed on the following Tuesday, at home against Wake Forest, the same day excerpts from O’Connor’s long-anticipated biography dropped. O’Connor, a respected columnist for the New York Post, interviewed more than 275 people over two years, and news stories started circulating online. The juiciest one said Coach K had hijacked the search for his replacement and kept Amaker from getting the job, with the goal of maintaining control of the program.

Krzyzewski started to spiral.

“He didn’t feel good all day because he was really upset,” Debbie K says. “He talks things out. He thinks out loud.”

She sat with him and talked about Amaker.

The situation is more nuanced than the headlines. Krzyzewski calls the claim “a cheap shot,” and the belief around Coach K is that the source quoted in the book overstated the coach’s desire for control once he’s gone. Amaker and Duke declined to comment on this subject. An anonymous person told O’Connor that Krzyzewski could be “Don Corleone” when he felt it necessary, and a source close to both Coach K and Amaker described O’Connor’s reporting to me as accurate. What’s clear from this private dispute being made public is that the succession plan left some damaged feelings. On the day the story became public, Krzyzewski worried that he’d hurt a member of the tribe. “He 100 percent has that guilt,” Debbie K says. “‘Did I do something that caused any harm that would bother Tommy? I love Tommy. He’s one of my boys. I don’t ever want anything to hurt my guys.'”

Sitting in his office, emotional and raw, he looked at his daughter.

“I just want to take care of everybody,” he said.

“You have and you are, Dad,” she told him.

She understood, too, the unspoken part of his emotional reaction, coming days after he turned 75, with just two games left to coach at Cameron.

“Even when you are not on the sideline,” she told him, “you will still be taking care of these people. They’re still your boys.”

That night, Krzyzewski led his team onto the court to play the Demon Deacons. Debbie and Mickie watched from upstairs during the first half until Debbie saw her daughter frantically waving her cell phone at her, as if to say: Check your texts. Debbie saw a message: Poppy doesn’t feel good.

Debbie slipped away from her mother, not wanting to worry her yet, and went down behind the bench to talk to the trainers. They told her they wanted to wait for the media timeout at under eight minutes to get him some Gatorade. Everyone agreed to meet in the locker room at halftime. Mickie Krzyzewski had seen all of this commotion and when Debbie returned upstairs, Mickie asked what was going on. Debbie explained that he felt lightheaded.

“I’m going,” Mickie said.

At halftime Krzyzewski struggled to keep his eyes open. His blood pressure was elevated. Doctors gave him fluids through an IV. When he recovered enough to watch the game, he started yelling about the officials and his blood pressure rose again. His daughter Jamie scolded him. “Dad, are you kidding me?” she said, according to her sister. “Really? This is what we’re doing? You’re gonna stroke out in the middle of a f—ing basketball game?”

He raged at himself, too, at time, at being 75, at losing some essential part of his K-ness.

“I sound like I’m weak!” he barked.

“You don’t sound weak,” Debbie told him. “You sound human.”

The team won, barely, and the beat reporters searched for news about Krzyzewski’s health. He spoke to his players briefly and then went home without breaking down the film, a tiny concession.

Later that night, Debbie texted with her mom.

“Where is he?” she asked.

“He’s rewatching the game,” Mickie replied, “but I convinced him to watch it from bed.”