One of the disappointments of the recently concluded Test series against South Africa was the performance of Ravichandran Ashwin. A tally of three wickets in six innings stood as proof for how ineffective he was with the ball during this series. Ashwin is a sure-fire match winner in Tests in India where the pitches offer turn from day one and the ball tends to keep low after pitching. But he has been much less effective on wickets outside the Indian subcontinent where pitches are not tailor made for the spinners. A tally of 300 wickets in India and a mere 130 outside the country in an almost equal number of matches shows the extent to which Ashwin is dependent on favourable pitches for picking up wickets.

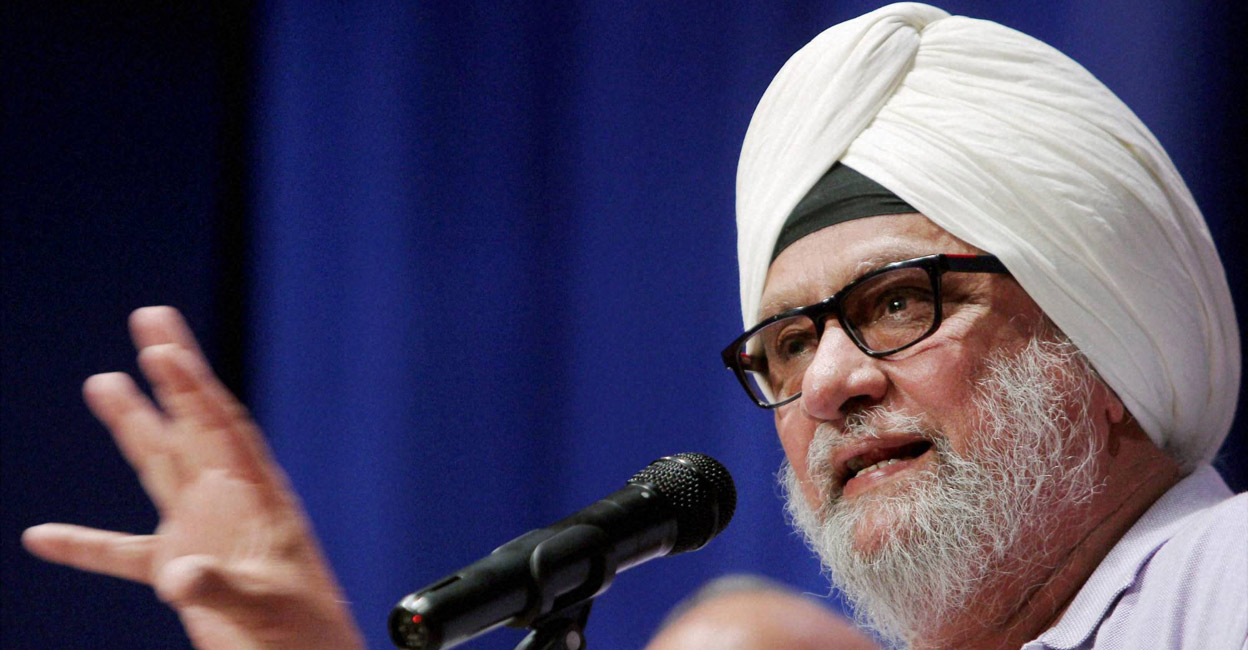

Another recent development was the retirement of Harbhajan Singh, an off spinner with 417 wickets in 103 Test matches to his credit. He finished with a tally of 265 wickets in India and 152 abroad and could bag five or more wickets in an innings on 19 occasions – 12 times at home and seven outside. These figures too indicate a high level of dependence on helpful pitches and home conditions for dismissing batsmen. Thus, both the off spinners who have turned their arm over for India during the current century have a heavily lopsided success ratio, with their effectiveness markedly reduced in pitches outside the country.

I am stating this to highlight the fact that this dependence on friendly tracks and home conditions was not a sine qua non for success during the era of the great spin quartet. This message was brought home by the realisation that the week that went by marked the 46th anniversary of the best ever bowling performance by an Indian bowler abroad. This was achieved by Erapalli Prasanna during the first Test of the series against New Zealand at Auckland in January, 1976. His bowling figures of 8/76 still remains the best by an Indian bowler on pitches outside our country. In fact only two other Indian bowlers have take eight wickets in an innings abroad – Kapil Dev and Anil Kumble. While Kapil picked up 8 wickets on two occasions – against Pakistan at Lahore in January, 1983, (8/85) and against Australia at Adelaide in December 1985 (8/106), while Kumble returned figures of 8/141 runs against Australia at Sydney in January, 2004.

The tour of New Zealand in 1976 was Prasanna’s second visit to the country. He was a member of the side led by Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi that toured the country for the first time ever in 1968. India won the four-Test series by a 3-1 margin and Prasanna was the hero as he finished with a tally of 24 wickets. He was ably supported by the left-arm spin of Bishan Singh Bedi and the Kiwi batsmen had no answer to the web spun around them by these two greats. Prasanna picked up eight wickets apiece in the third and fourth Tests that India won, while in the first Test, it was his bowling in second innings, where he picked 6/94, that set India on the path of victory. Thus, he had a prominent role to play in India’s first ever series win on foreign soil.

While going through the career statistics of Prasanna, an interesting fact came to light. He played in 49 Tests for India, during a period spread over 17 years and picked up a total of 189 wickets – 95 at home and 94 abroad. Further he had two match hauls of 10 wickets- one each at home and abroad. He picked up five wickets or more in an innings on 10 occasions – 5 each inside India and outside! Thus, one can see that Prasanna was equally effective both in home conditions and on foreign soil.

A look at the performances of the other three members of the spin quartet will also reveal that they were as comfortable bowling abroad as they were at home. Bedi played 67 Tests and took 266 wickets (139 in India and 127 outside) while Bhagwat Chandrasekhar (Chandra), who took part in 58 matches, scalped 242 (142 within the country and 100 outside). Srinivas Venkataraghavan (Venkat), the fourth member of the quartet was in the playing eleven in 57 games and finished with 156 victims (94 on home terrain and 62 abroad). Bedi had five five-wicket hauls at home as against six abroad. His only 10-wicket haul also took place on foreign soil. Chandra took five wickets or more in an innings on 16 occasions – 8 each at home and abroad and had two 10 wicket hauls, again split equally.

From the above, it emerges clearly that all the four spin bowlers who played for India from the 1960s through the 1970s were comfortable playing on pitches abroad which were not tailored to their needs. While Prasanna could boast of a record abroad that was at par with what he had in India, Bedi’s tally on grounds outside India was only marginally below what he picked up in Tests in India. Though Chandra and Venkat picked up more wickets in India, they were effective on pitches outside as well. It was Chandra’s amazing spell that turned around the game at the Oval in 1971 and set India on the path to their first ever test victory in England. Similarly, he ran through the Aussies at Melbourne in 1977 to set up India’s first ever win in Australia. Venkat was a force to reckon with on the hard pitches in West Indies that offered plenty of bounce and was successful during his three tours of the Carbibean islands.

It is not fair to compare the players of an earlier generation with those of the present one as conditions under which the game is played has undergone a significant change. The biggest change is the advent of limited overs cricket – first in the form of One-Day Internationals (ODIs) and later through an even shorter T20. Prasanna did not play in even a single limited overs match at the international level while Chandra featured in only one ODI. Bedi played in 10 ODIs and Venkat, who led India in the first two World Cups, took part in 15. Thus they did not have to adjust their bowling styles to suit the requirement of limited overs cricket though Bedi and Venkat had played as professionals for counties in England and were exposed to the shorter version of the game at the first-class level.

Further, spin bowlers were often the sole wicket-takers for India during the period they played as our fast bowling attack was so weak as to be considered as non existent. Cricketers are required to play almost round the year at present and there has been an increase in the number of Test matches as well. This has placed greater work load on present day players with the need for much higher levels of physical fitness. An added benefit of higher fitness standards is the improvement in fielding, both close to the wickets and in the deep. It also merits mention that both Ashwin and Harbhajan are fairly good batsmen with centuries in Test cricket against their name. Amongst the older lot, Venkat was the only one who could be called a decent performer with the willow, though Bedi too has a half-century to his name in Test cricket. Chandra was the classic No. 11 who did not believe in troubling the scorers while Prasanna was just one notch above that.

From the above analysis one can safely conclude that spinners of the yore were better performers with the ball on pitches outside India than the present lot. They could also turn out match-winning performances with more ease and consistency than the spin bowlers of the present generations. However, the current set of spinners are more versatile and have adjusted to the demands of playing in different versions of the game with ease and aplomb.

(The author is a former international cricket umpire and a senior bureaucrat)