Now 16 years old and just over a year away from graduating from high school, D’Angelo Ortiz inhabits the same kind of playground he’s been in since he could walk.

All of his life, from his earliest memories, he’s had one vocational goal — and that’s to be a baseball player.

“Just a baseball player,” confirmed D’Angelo. “I’ve still got to get my work in, but, baseball player, that’s it. That’s all it is.”

It’s something that means everything to him.

Millions upon millions have had the same dream, but D’Angelo’s story is a little different.

His father, David, is a living legend who is considered iconic in Boston and the Dominican Republic — and beloved even by most casual baseball followers.

The long shadow Big Papi casts is one D’Angelo — who now stands 6-foot and weighs roughly 200 pounds — has no fear of. In fact, he embraces it.

Perhaps because he has been happily walking and even running joyfully in that shadow for most of his life.

“To have him as a resource is amazing,” said D’Angelo. “I’ll never use that as an excuse. I love pressure and I love … those butterflies in my stomach and I love people not expecting me to follow in his footsteps and me just walking right into them. It’s something that I love.”

Attending Westminster Christian School in South Florida, which has an elite baseball program that has produced five Major Leaguers (Alex Rodriguez, Doug Mientkiewicz, J.P. Arencibia, Dan Perkins and Mickey Lopez), D’Angelo aims to be the sixth.

In fact, the rich baseball tradition of his school drives him rather than daunts him. Before walking into the home dugout, you can’t help but notice the sign with an MLB logo above it that lists the five Major Leaguers who have come out of Westminster.

“I want to be the best one on that list. That’s how I’ve thought since the first day that I came here — and it’s not something to just talk about,” said D’Angelo. “It’s a grind every day that you see that wall and it makes you want to work harder. To know that this is a school that, if you do what you need to do, you can go somewhere, that’s motivating in itself.”

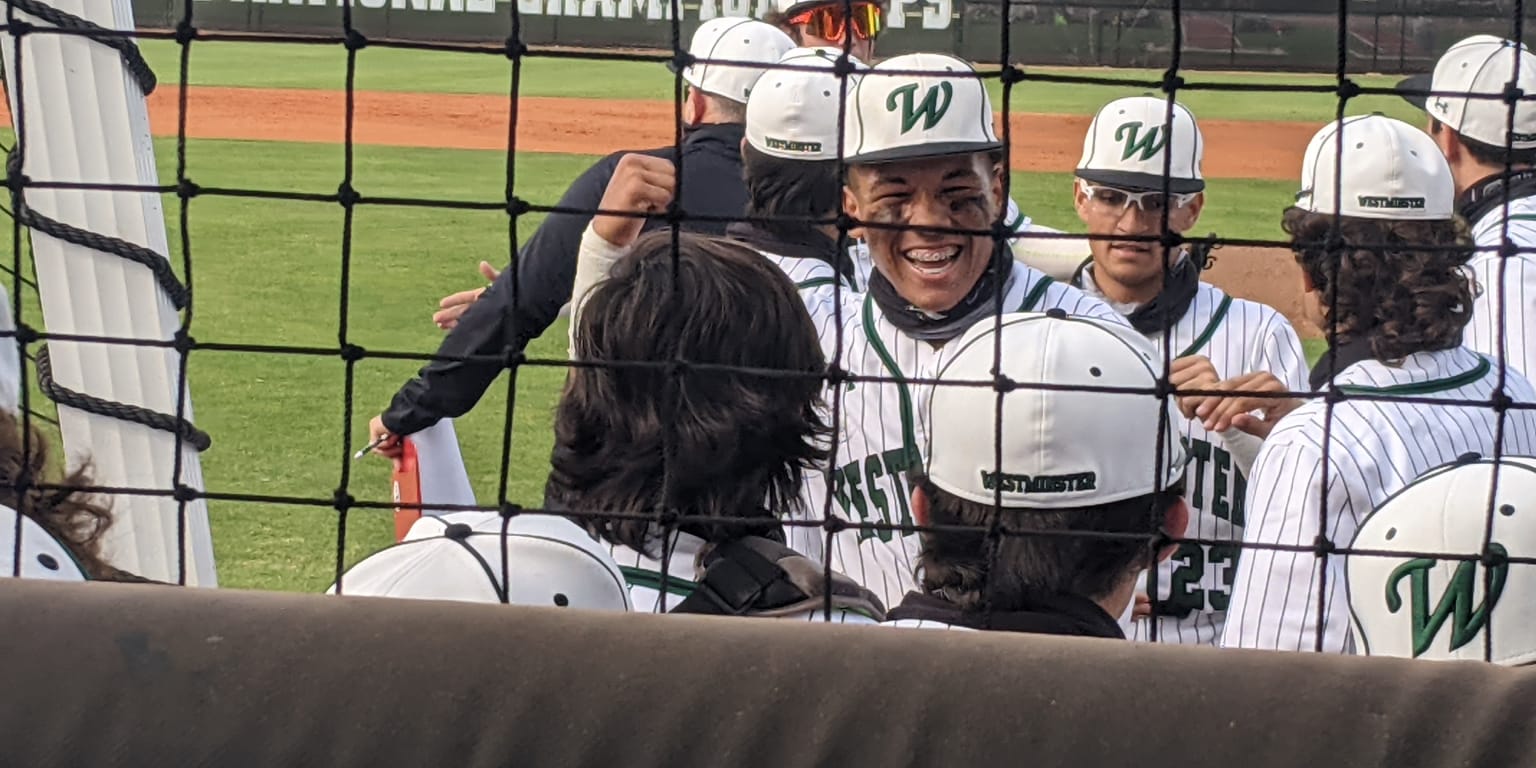

Spend two minutes around D’Angelo and it’s clear how self-motivated he is. Spend an afternoon watching him play, and it’s clear how genuine his joy for the game and his teammates is. His smile while wearing a uniform is as enormous as it is infectious.

In a recent home game, first baseman D’Angelo was on the receiving end of an inning-ending double play. He beamed from ear to ear coming back to the dugout as if his team had just clinched a playoff berth or he had hit a walk-off homer.

Clearly, such enthusiasm is in his bloodline.

“Always,” D’Angelo said. “I feel that to be able to stand on a baseball field is such a blessing. There are kids in the hospital right now. There are kids going through so many things. To be able to play on a baseball field — win, lose, draw, go 0-for-4, or 4-for-4 — just to be able to go out there, it’s amazing.”

Feeling the Draft

At last, D’Angelo’s goal is starting to come into focus. If things go like he hopes, the high school junior will be selected by one of 30 MLB teams in the 2022 Draft. He knows there is a lot to do between now and then, but the thought of being under the employ of a Major League franchise is one that consumes him.

But D’Angelo doesn’t just want the glory of baseball. He wants the entire experience, including the inevitable struggles.

“That’s my only goal,” D’Angelo said of the prospect of getting taken in the ’22 Draft. “Basically, it’s something that every morning I wake up, I wake up for that day or for that day that I get to go into pro ball.

“What people don’t understand, too, is that day that you go into pro ball, it’s just the beginning. It’s doesn’t mean you did anything. That’s the beginning — and that’s where people figure out whether you’re really built for this sport. So this is the very, very beginning, and I’ve got a ways to go. But I’m all for it and I want every part of the journey.”

Meanwhile, his father will cheer him, teach him and give him advice without prodding him.

“I mean, what else can I ask for? I don’t want him to be all up on me,” said D’Angelo. “I like smiling on the field. That’s it. So, that’s the only way to play baseball.”

His mother, Tiffany, David’s wife of over two decades, will continue to support D’Angelo’s dreams while making sure he keeps up with all the other non-baseball details of life.

“I got him to do the dishes earlier today,” chuckled Tiffany, before turning serious. “It’s very exciting, I’m very impressed with D. He’s putting in a lot of hard work, right now.”

While David likes D’Angelo’s power swing, ability to hit to all fields and disciplined approach at the plate, he feels like his son’s work ethic could end up being his biggest separator.

“D is taking this very serious. I’m telling you that, right now. He wants it,” said the elder Ortiz. “I’m not putting any pressure on him. What I want him to do is educate himself. It’s not like I’m putting him against the ropes. The one thing that me and Tiff want is for him to educate himself, get good grades and we support him on the baseball thing. He doesn’t need to be pushed. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. He’s pushing himself.”

David Ortiz knows there is so much that goes into the making of a pro ballplayer — and he’s not about to forecast his son’s Draft prospects over a year ahead of time or say if he might be better off playing in college first. D’Angelo’s body and skillset are still developing. The entire family wants to see how the situation plays out over the next year-plus.

“We’ll see how he develops, then we’ll figure out how to go. I want him to be ready [when he goes into pro ball],” David said. “You know what? To be honest with you, if he continues working the way he is, I’ll tell you what, when I was his age, when it comes down to recognizing those things, he’s way more mature than me. It all depends on how he develops. I will know. I will know.”

When those words by David were relayed to D’Angelo, you could see the fire in his eyes.

“He’ll know, and I’ll be ready,” vowed D’Angelo. “He’s just got to keep [providing those baseball pointers] that he [gives] and watch the games, and we’ll be good. I’ll put the work in.”

Unlike his father, D’Angelo is a right-handed hitter and thrower. Instead of wearing No. 34, D’Angelo currently sports “12” on the back of his jersey.

Despite his ties to perhaps the greatest designated hitter in baseball history, D’Angelo has no plans of making his living as a DH. A corner infielder, D’Angelo hopes to become a third baseman. He even receives pointers from his father’s former World Series-winning teammate, Mike Lowell, who lives nearby.

In fact, Lowell sometimes gives pregame motivational speeches to D’Angelo’s team, though David ribbed his friend by saying those speeches might stop because the team recently lost after one of them.

Inspired by other baseball father-son combos

When Ken Griffey Jr. burst onto the scene and emerged into baseball’s signature player by the mid-1990s, it felt like a novelty for a baseball son to so effortlessly follow in his father’s path.

Lately, however, it has become more common. Fernando Tatis Jr., at 22 years old, just signed a 14-year, $340 million contract extension with San Diego. For perspective, David Ortiz earned roughly $160 million in his 20-year career that ended in 2016.

In Toronto, they are expecting big things from two sons of Hall of Famers: Cavan Biggio and Vladimir Guerrero Jr.

You’d have to think it is enormously helpful for D’Angelo to see others succeeding in the same line of high-profile work as their dads.

“A hundred percent,” said D’Angelo. “[When] I see Vladdy and Tatis, I think, ‘Wow, they’re amazing. I want to be better.’ I see their contracts, I see that $340 [million], I say, ‘I’m the next one.’ That’s basically how I think and [I] don’t say that because it’s something that [I need] to say. I say that because I devote 100 percent as much time to baseball as I can.

“And I know that’s what they did, and I know that there’s bad days, there’s good days, but that work, it pays off. So, so I’m going to be in the same exact spot. It’s just staying healthy and taking care of myself. That’s it.”

By the way, David and Vladimir Sr. — both Dominican-born — couldn’t have a closer friendship if they were brothers. It has been that way for decades.

“You want me to be honest with you? Vladdy sends me to talk to his son,” said David Ortiz with a deep laugh. “He’s like, ‘Hey, go and talk to him because he’ll listen to you more than he’ll listen to me.’ The reality is, I’m pretty sure Vladdy has put a lot of work into Vladdy Jr. just like Fernando Tatis’ father — and you know, me and him, we also go way back.

“The same way I give advice to D, they do that with their sons. The reality is that, at the end of the day, they listen to you. But whenever somebody else that isn’t the same will talk to them, sometimes it even works better.”

D’Angelo admits that sometimes Lowell is the one who knows exactly what to say to him, and he also notes how helpful his coaches at Westminster have been. Though D’Angelo says sometimes he likes a short break from listening to David — as just about any kid will with their parents — he always winds up going back to that well.

“In my case, I’m lucky enough to say that D always wants me to talk to him about baseball and tell him things,” David said.

Welcome (back) to Miami!

For the 2019-20 school year, D’Angelo moved across the state to Bradenton, Fla., to attend a boarding school called IMG Academy that is geared toward aspiring pro athletes.

David sensed that D’Angelo didn’t quite seem like himself there. On the other hand, Tiffany appreciates the way her son learned more responsibility while living on his own.

D’Angelo’s review of IMG was that “it wasn’t bad.”

The entire family agrees that being back together in Miami — and D’Angelo’s transfer to Westminster Christian — is best for all.

“He’s a guy, he loves being at home. Every time we had to go out there to see him, the guy didn’t want to show us that he wasn’t in the right place. But he likes to be at home,” said David. “This guy, when he’s here, he doesn’t go [anywhere]. He likes to be at his house. He likes to be close to his family. It’s good to have him around so we can watch him closely. I think IMG is a good place, but it works different for everybody. We weren’t seeing the effect that we were expecting from him being out there. It was probably because of the distance, or whatever, I don’t know.”

Now, David Ortiz can get into his car, drive about five minutes and get there in time for D’Angelo’s home games, which typically start at 3:30 p.m.

At a recent game, David timed his entrance perfectly and inconspicuously, as he walked up a few steps and put a portable chair down on the first available metal-bleacher seat. There was no buzz when David came in. He was another father there to watch his son play a game. If this scene had taken place at a Boston-area school, it would have been a madhouse.

David, wearing a “Baseball is Life” T-shirt, watched the game quietly for the most part. After D’Angelo’s first at-bat, he looked up to his father and bemoaned that the opposing pitcher was throwing off his timing by throwing too softly.

“That’s why you got to stay back,” David reminded him.

That day, D’Angelo walked in his first at-bat, lined out to center his second time up and hit an absolute laser beam which the shortstop caught in his final time at the plate. In a game his team wound up winning, 3-1, D’Angelo clearly wasn’t consumed by his individual at-bats or plays in the field. Instead, he expended most of his energy cheering and interacting with his teammates.

Later in the game, when an errant throw skipped past him on what could have been a lineout double play, he mentioned to his father that he should have set his feet differently. David reminded him to keep both feet on the bag before the throw arrives, so he can quickly move in either direction. D’Angelo nodded.

There are times throughout the game David encouraged other Westminster players. “Nice swing,” he said to one. “Great hustle,” he told another.

Due to the pandemic, Big Papi is masked up through the entire game and also not able to go to Red Sox Spring Training for the first time since he retired.

“This is my Spring Training,” David said proudly, while watching his son play baseball.

Late bloomer

D’Angelo knows he has to work harder than his peers because he’s only lived in Florida full-time since 2017, the year after his father retired. In Florida, they play baseball 12 months a year. In Boston, with its harsh winters and chilly springs, it wasn’t anything like that. In other words, D’Angelo plays with and competes against kids who have played year-round all their lives.

“His body has changed. That baby fat that he used to have is long gone,” David said of D’Angelo.

How much has that move south propelled him forward and made his goals more realistic?

“A lot, because my work ethic is there,” D’Angelo said. “You put me in Antarctica, you show me how to work, I’m gonna work. So I mean, it’s just being down here where you’ve got such competition, that’s something that you’ve just got to love. And if you’re a true competitor, Miami’s a good place to play baseball.”

While driving to a recent Westminster game with Tiffany, David spoke through the Bluetooth of his car speaker to explain how important the family’s post-retirement move to Florida has been to D’Angelo’s development.

“[It’s helped] a lot,” David Ortiz said. “Put it this way. We’re on our way to watch a baseball game [in February]. He’s in an environment where he sees competition. Kids down here, they compete. I’m not saying that up there [in Boston] they don’t compete. But if you practice half a year, it’s not the same as if you’re doing it all year-round. That makes a huge difference.”

It is also the reason D’Angelo thinks he is going to be a much better baseball player by the 2022 Draft than he is currently.

“Honestly, the improvement that I’ve seen in the past three months is something that … in a year from now, I don’t try to think about where exactly I’ll be, but I’ll let it happen,” said D’Angelo. “I don’t look at it as work. I look at it as a passion. You know what I mean?”

Future Red Sox?

It is one thing for D’Angelo to embrace the thought of playing pro ball.

But it would probably seem a little overwhelming to both father and son if he wound up with the Red Sox, right?

After all, perhaps only Ted Williams has had a larger impact on Boston baseball than David Ortiz, who guided the team to three World Series championships and provided 14 years of clutch hits.

Interestingly — and somewhat surprisingly — father and son both expressed hope that will happen when asked about it independently.

“I would love to [see it],” said David. “I would love it, to be honest with you. That would be like a dream come true. Could you imagine?”

D’Angelo tries not to think too far ahead, because the thought is almost too appetizing.

“I would love it,” D’Angelo said. “I think that just growing up in Boston, that motivates me like nothing else. I love Boston, too. And I love the city. I can’t ask where to go. I just ask to be picked up eventually. But Boston is somewhere that it’s in the back of my mind. I love that city. The same feeling I get when I walk in my house is what I get when I walk into Fenway. I’m comfortable there.”

If that ever happened, it’s even possible he could bring some of his father’s legendary swag with him.

It was hard not to notice D’Angelo Ortiz wearing a gold elbow guard during his at-bats at a recent game.

“I was watching [Alex] Verdugo, and he had it. He had a smaller one. And I just want to be the swaggiest on the field,” said D’Angelo. “I feel that you can’t be the swaggiest and not do something. But I feel that if you look good, it’s going to motivate you to play well.”

Just don’t mistake D’Angelo’s swag for being cocky.

“Baseball is a business where you’ve got to contribute,” D’Angelo said. “Nothing’s given to you. I’ve been learning that in the past few months — that no matter who you are in baseball, you have to work for positions, for spots in the lineup, whatever it is.”