“DO YOU HATE baseball?”

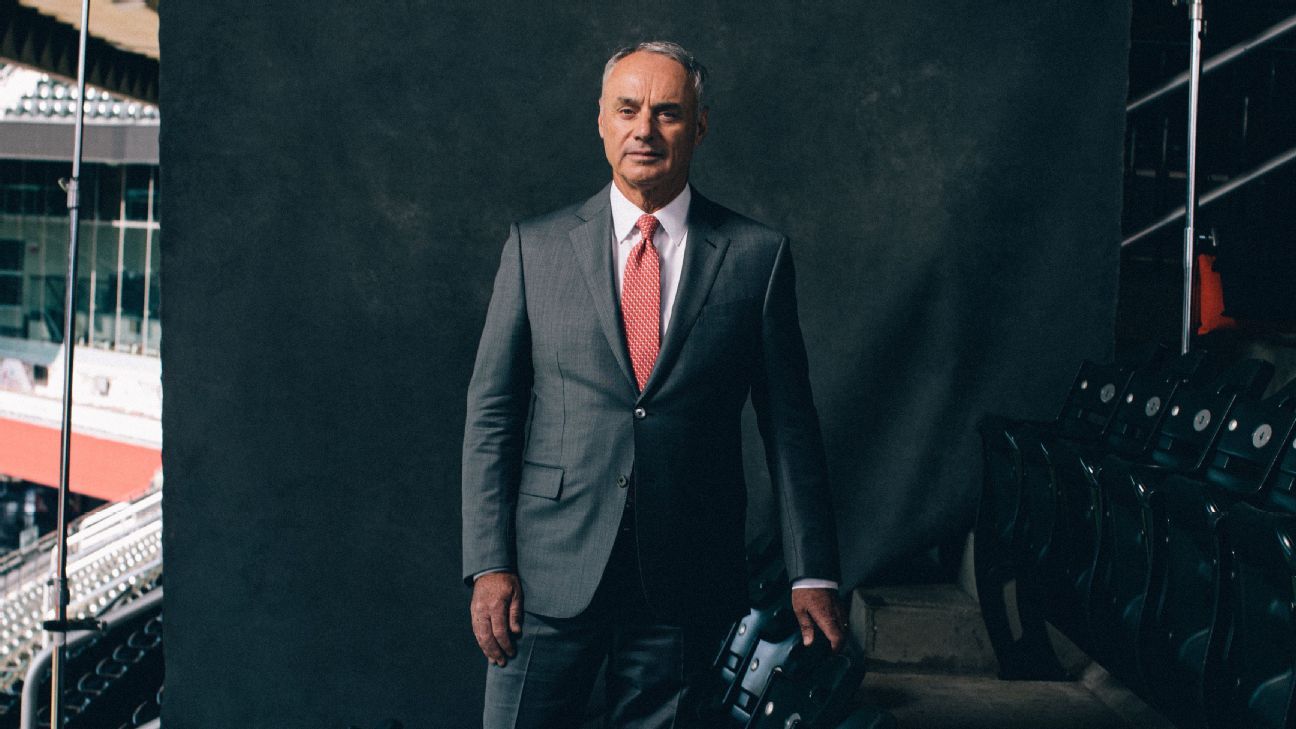

I pose this question to Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred deep into an interview at Citi Field in New York.

“It is the most ridiculous thing, among some fairly ridiculous things that get said about me,” he says. “The assertion that I hate the game — that one does rub me the wrong way, I have to tell you the truth.”

ESPN Daily: Don Van Natta Jr. talks with host Pablo Torre about his profile of Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred. Listen

ESPN on YouTube: Extended outtakes from Van Natta’s exclusive interviews with Manfred. Watch

The loathing of sports commissioners is a sport all its own in America, and perhaps few get ripped, blamed, mocked, cursed and memed more than 63-year-old Robert D. Manfred Jr., now in his eighth year at the helm of MLB. Detractors are convinced that the labor-lawyer-turned-commissioner is bored by baseball, is killing baseball and is only interested in baseball to make his rich bosses richer.

Manfred says they couldn’t be more wrong. He recalls the day — Saturday, Aug. 10, 1968 — when he and his father took a four-hour drive from their upstate New York home to the Bronx to watch their favorite team play at Yankee Stadium. He was 9.

“It was the first game I ever saw in my life,” he says. “I remember how I felt walking into that stadium. The field was just so immaculate. I actually loved the game before I got there, and even more when I left. It’s really that simple.

“And it’s not me that matters, at the end of the day. It’s the game that matters.”

OPENING DAY WAS about to be canceled by Rob Manfred on national television. It was Tuesday afternoon, March 1 — Day 90 of the stalemate between Major League Baseball’s billionaire owners and its millionaire players. Manfred stood behind a podium outside a ballpark in Jupiter, Florida, to deliver the grim news: Negotiations had broken down, and he was canceling the first two series of the 2022 regular season. But just before he spoke, Manfred looked directly into the camera and … smiled.

The fleeting grin, hours after a photographer caught him practicing his golf swing, was all Manfred’s legion of haters needed: “Manfred has to go,” tweeted Chicago Cubs pitcher Marcus Stroman. “We need a new commissioner asap!”

1 Related

Two days later, Manfred was back at MLB’s midtown Manhattan headquarters to preside over an all-hands meeting of nearly 1,000 MLB employees, some assembled in a large atrium and others joining via Zoom. The mood was somber. Manfred had called the session to update league employees on the lockout and offer an explanation for his ill-timed smile (For the record, he says it was a friendly gesture toward a reporter who approached to place a recording device on the podium just as Manfred was looking for somewhere to lay his notes).

“I’m getting killed out there,” he confessed.

“Getting killed” has become an inescapable fact in Manfred’s professional life. On social media, Manfred’s moves and motives, gaffes and goofs have become 24/7 targets by fans who hold him accountable for every conceivable problem:

A crew of umpires forgets the pitch count and needs four minutes, 15 seconds to figure it out? Mistake-prone umpires: Manfred’s fault.

A potential walk-off homer dies on the warning track? Dead baseballs: Manfred’s fault.

A 40-year-low “crowd” of 2,488 attends a game in Oakland? Fans are boycotting a low-payroll team playing in a ramshackle stadium: Manfred’s fault.

Manfred gets knocked for things that are arguably out of his control. He also gets crushed for his actions — or inaction — during some of MLB’s trickiest crises, including the steroids investigation he oversaw before he became commissioner and the major cheating scandal under his watch that made a mockery of the integrity of the game — and a World Series. Some players say they don’t trust the commissioner to have the best interests of the game at heart.

I asked Manfred to name the biggest mistake he’s made — one decision he’d like to have back. He laughed. “I have to narrow it down to one?” he said. “You know, I think people who can’t admit they’ve made mistakes, particularly in a job like this, are a little dangerous.”

Manfred insists he’s trying to do the opposite of ruin baseball. His goal, he says, is to revolutionize the American game most resistant to innovation by pushing through rules changes to speed things up, add more action and, ultimately, attract more fans. Critics counter that his push to hurry baseball along with “ghost runners,” and his push for pitch clocks, only proves how much he hates the game.

“Yeah, here’s the problem,” Manfred says. “When you acknowledge there’s something wrong with the game, that turns you into a hater of baseball.”

Can one of baseball’s most hated men usher the game into a brighter future by returning it to its glorious past?

My quest to answer that question began in an Iowa cornfield.

IT’S 3 P.M. ON an oppressively humid August day in Dyersville, Iowa.

Manfred is in deep center field of the “Field of Dreams” movie set, clad in a black MLB “Field of Dreams” polo shirt, khaki pants and black dress shoes. A dirt path carved through Hollywood’s most famous patch of corn connects the old field to the gleaming 8,000-seat ballpark, built by MLB. Tonight, the Chicago White Sox, in their iconic Black Sox-era uniforms, will face the New York Yankees in their vintage grays, for the first Major League Baseball game in the state of Iowa.

“Great to meet you, Mr. Commissioner,” I say.

“Call me Rob.”

I tell him one of his golfing buddies, Frank X. Queally Jr., had urged me to find out why his handicap had inched up to 12. “No way!” Manfred says, smiling as he digs out his iPhone and punches up an app to show me his PGA-graded handicap of 7.3. “Facts are facts,” he laughs.

Through the blast-furnace heat, we walk toward the low-slung ballpark, an early 20th century throwback with its manual scoreboard in right field. Corn stalks ring the outfield and stretch toward the horizon. Manfred chatters about the anticipation for tonight’s nationally televised game, particularly among the players who rode buses from the Dubuque, Iowa, airport, past miles of cows and farmland. Old-school.

“I’m so proud we were able to pull this off,” Manfred says. “Today is a damn good day.” I ask if the inaugural Field of Dreams game will become a mid-August tradition. “Look, it’s a no-brainer,” he says. In this setting, you’d never know the commissioner was a social media pariah; fans of all ages seek selfies and his autograph on baseballs, programs and caps.

An hour later, I meet with Manfred in an icy-cool room a few dozen paces behind home plate. I ask the commissioner for extended interview time. He scowls.

“As a lifelong baseball fan,” I tell him, “I feel as if I really don’t know you. Well, except for all the memes about how much you hate baseball.”

“The usual Twitter nonsense,” he says, laughing.

I tell him I want to try to understand the thinking behind his past decisions and, even more, explore his vision for baseball’s future. “The Manfred Doctrine,” I call it. He smiles, warming, perhaps, to the idea. But he told me he’s a private person who is uncomfortable opening up to reporters. (Manfred has been married to his wife, Colleen, for more than four decades, and they have four children and five grandchildren.) He’s also quick to say he’s really not interested in “rehashing past stuff,” like his non-punishment of the Houston Astros players who cheated their way to the 2017 World Series title. “It was stupid,” he says of his now-infamous comment in February 2020 that it made no sense to confiscate the team’s World Series trophy because, after all, it’s just “a piece of metal.” Two days later, he apologized. Now, he’s telling me: “The piece of metal thing — the worst.”

Manfred explains that the surest way to grow the game is to introduce ways to improve how it’s played and restore it to a better, quicker version of itself — more like it was played decades ago. “Theo Epstein says it best — I’m paying him now so I can steal it — I’m trying to make the game the very best it can be.”

“Easier said than done,” I say. Manfred nods. “All right, let’s do it,” he finally says, before shaking my hand and taking off.

A half hour later, before a half-dozen cameras, Manfred sits down next to Kevin Costner. The relaxed, jocular Manfred I’ve just met is gone, replaced by a coiled, stiff Manfred. This is the buttoned-up commissioner we often see, offering lawyerly, literal answers when delivering bad news. You wouldn’t know this was a great day for baseball. “He should pay for media training,” a former MLB executive says. “It might be a good investment.”

What I’d learn about Manfred is that he doesn’t hesitate to blame himself for the gaffes that have caused him so much trouble — and sometimes in a surprisingly candid, self-deprecating way. But when confronted with questions about his record, he often bristles defensively, offers multipronged rationalizations for his decisions and sometimes pins blame on others despite insisting he’s thick-skinned.

But that’s not how he’s seen by his loyal lieutenants and the owners I interviewed.

“He’s probably direct to a fault,” says St. Louis Cardinals owner William O. DeWitt Jr., who adds that the commissioner “does an excellent job.” “He’s not that political in the sense of making everybody feel great. He says what he thinks.”

“He absolutely is not afraid to give it to you,” says Epstein, the former Red Sox GM and the Cubs’ ex-president of baseball operations, hired by Manfred to consult on rules changes. “He’s not afraid to make jokes at his own expense either. He does seem to know how to have a good time.”

That Manfred is a guy fans rarely see. Away from the cameras, he comes off as authentic, self-effacing and rarely passes on the chance to needle one of his deputies and, eventually, me. A guy you’d want to have a beer or two with (Manfred’s drink of choice is lager, usually Stella Artois). Queally, the golf buddy, describes Manfred as “very upstate New York, plain-spoken,” and also “a f—ing huge ballbuster.”

As the sun begins to set on Iowa, and a sentimental soundtrack plays over stadium speakers, Costner emerges from the corn stalks, followed by the players. Holding a baseball in both hands, he tells the crowd, “We’ve come to see the first-place White Sox play the mighty Yankees in a field that was once corn. It’s perfect.”

Hours later, the game delivers a perfect Hollywood ending when White Sox shortstop Tim Anderson smacks a walk-off home run into the cornfield in right, followed by a blaze of fireworks.

AS LONG AS anyone can remember, the game has been in trouble. It has always existed in a perpetual state of failing to dazzle young people, always mired in an existential crisis, always teetering on the edge of oblivion. “Baseball is dull — they’ve been saying this stuff for more than 60 years,” says Bud Selig, Manfred’s 87-year-old predecessor and mentor.

Selig recalls that a long-forgotten Milwaukee Journal sports editor named Oliver Kuechle once declared, “Baseball is a moribund sport.” That was in 1961. Kuechle added, presciently, “Football, specifically pro football, will shortly become our national pastime.”

Today the National Football League is more than just America’s most popular sport; it’s a money-printing machine and a year-round cultural obsession seemingly unaffected by scandal. MLB finds itself eclipsed in popularity by the National Basketball Association, particularly among young fans, and fending off upstarts such as Formula One and Major League Soccer.

Leaguewide attendance totals are down considerably this season (as compared with pre-pandemic totals), on pace to be the lowest since 1996. Among all American fans who watch sports on television, baseball fans are the oldest: the median age is 57, up from 52 a generation ago.

How much of the game’s current existential crisis should be blamed on Manfred depends on whom you ask, though even his allies agree he’s been slow to change the game. “The sport is like everything else in life — it evolves, it needs to do things, it needs to change, starting with the pace of the game,” Selig says. “That’s Rob’s challenge.”

I want to dig in on what bothers Manfred about the game.

“How many hours of baseball do you watch in a week?” I ask him.

“Oh,” he says, pausing a moment. “So, let me count nights. I would say that I probably watch in the evening, at least four nights a week — a game or games. So there’s 12 hours and I always have it on in the office — the MLB Network games during the day. So, in excess of 20 hours.”

In the evenings, Manfred tends to watch more than one game at a time at his Upper East Side apartment. “I will confess, I watch a lot of New York baseball, both the Yankees and Mets.”

“And when you watch baseball as a fan, what’s your biggest aggravation?”

“I think the same sort of sentiments that we hear from our fans in terms of pace of the game,” he says. “I think the pace issue, the action issue, is more acute in a broadcast than it is at the ballpark.”

Several new rules have already been implemented to accelerate the pace, and none have really worked. One is a relief pitcher — unless he is injured — must face three batters or complete an inning before being replaced to cut down on pitchers’ changes. Another is the “ghost runner” placed on second base in extra innings, a rule that exists to end a game faster. Through Sunday, the average nine-inning game this season was 3 hours, 5 minutes, only 5 minutes shorter than last season’s all-time record high. MLB internal research finds that not only do most fans believe the games go on too long, they’re frustrated that there’s often too little action, a lethal combination. This year’s leaguewide batting average stands at a paltry .242, the lowest since 1968. Home runs and run-scoring are down, while strikeouts are near the all-time high.

Even the game’s more conservative owners complain that games stretching three to four hours must end. “The game has changed and it has changed for the worse,” says DeWitt Jr., the 80-year-old Cardinals owner. “To be honest, players get out of the box and fool around for no reason. Come on, get in the box! And the pitcher is walking around the mound. I don’t know what they’re doing. … The game needs fixing. It’s just slow.”

Manfred agrees with that assessment. He tells me, in terms far more certain than he has laid out publicly before, that he fully supports revamping the game with pitch clocks, the elimination of the shift and, in 2024, some form of robo-umpires. Now he must sell those changes to players and fans, some of whom believe he doesn’t have baseball’s best interests at heart. A big challenge, for sure, but one Manfred doesn’t believe is insurmountable. “I think that people pay a lot of attention, can be hypercritical if not downright mean,” he says. “That’s actually a good thing for the game’s future.”

MANFRED WAS BORN on Sept. 28, 1958, in Rome, New York, a one-hour drive from Cooperstown. One of the middle-class town’s biggest employers was Revere Copper and Brass, then America’s largest copper rolling mill, where Manfred’s father, Rob Sr., supervised production as the works manager. Manfred’s mother, Phyllis, taught third-graders. Manfred was the middle of three children, and his parents instilled in them a love of learning and an obsession with sports.

The Manfreds belonged to the local country club. Manfred’s older sister, Lynn, was an all-sport phenom, winning 18 varsity letters. As a boy, Manfred played tennis, golf and, in Rome’s Farm League and Little League, second base and shortstop. All glove, no bat. “I was dismal,” he says. Manfred recalls facing a hard-throwing pitcher named Mark Puffer who “looked like he was 6-foot-5.” “Never saw it,” he says of his fastball.

When cable TV arrived in Rome, father and son rarely missed a Yankees game. “New York Yankees baseball was what we did on summer nights,” he says.

At the first game he attended with his father at Yankee Stadium, Manfred and his father sat between home plate and first base on Old-Timers’ Day (In attendance was Gen. William D. Eckert, MLB’s fourth commissioner). Mickey Mantle hit a pair of solo home runs in a 3-2 loss to the Twins that took 2 hours, 34 minutes. Manfred looks wistful as he recalls the way the game was played then. No analytics, no pitch counts, no defensive shifts and no four-hour games.

Nothing was more important than baseball in Manfred’s relationship with his hypercompetitive, sports-mad father, who died in 2018 at the age of 87. Baseball was a gift from his dad, whom he called “Rob,” that Manfred still cherishes. The game’s intricacies and mysteries became their shared language. Their love of the Yankees was their common ground.

After eighth grade, Manfred traded his glove for a racket. He was a natural, starring on the tennis team at Rome Free Academy, the public high school. In addition to being an overachiever in the classroom, Manfred was hypercompetitive at all sports and games, a trait inherited from his dad.

Manfred played on the tennis team at nearby Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York. Before his junior year, he transferred to Cornell University, where he earned a degree in industrial labor relations. In the spring of his senior year, Manfred interviewed for a labor relations job with Union Carbide, a gig he desperately wanted, or had thought he did. “I get on this little plane … I’m watching out the window, flying to Texas City,” he says. After the interview, he thought, “Oh s—, I ain’t going back. There’s no way I’m living here.”

In his mailbox back home, he found an acceptance letter from Harvard Law School.

After graduating magna cum laude and clerking for a federal judge in Boston, Manfred was hired by Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, the powerful white-shoe law firm, where a partner named Chuck O’Connor became his mentor. One of the firm’s biggest clients was Anheuser-Busch, the beer conglomerate that owned the St. Louis Cardinals at the time. Through the beer connection, MLB’s owners hired the law firm as an outside counsel. “You want to do this baseball thing?” O’Connor asked Manfred, then 30 years old.

O’Connor became the owners’ lead negotiator with the players’ union, and he recruited Manfred to help. Manfred was awed by O’Connor’s skill as “a masterful negotiator.” “It takes more balls to make a deal than it does to have to not make a deal,” O’Connor often said, a lesson Manfred never forgot. At the time, the commissioner was Fay Vincent. During the 1990 collective bargaining agreement negotiations, Manfred later discovered that Vincent, behind O’Connor and his back, had offered the players a series of concessions, including, for the first time, minimum salaries of $100,000.

Manfred was hardly alone in his anger at Vincent. The owners viewed the concessions as an unforgivable betrayal, an assessment that worked to Manfred’s advantage. Prior to the September 1992 owners meeting, Selig gave Manfred some advice: Stay away from the meeting. Selig knew the owners were poised to fire Vincent — who ended up resigning, to be replaced by Selig — and Manfred would benefit politically from being nowhere in sight.

In August 1994, the players went on a strike that wiped out the remainder of the season and the World Series, a disaster that infuriated fans. Manfred had a front-row seat to the damage done to the game by the failure to strike a deal. “Oh, it was the worst year of my life,” he says.

In 1998, Selig offered Manfred a full-time job with MLB as executive vice president of labor and human resources. Manfred joined MLB’s executive suite during the thrilling summer when Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, later implicated as steroids users, shattered baseball’s single-season home-run record. The canceled World Series quickly became a distant memory.

THE OVERARCHING LESSON Bud Selig says he tried to teach Manfred was that leading baseball is “a political job,” one in which you must broker a fragile peace, not just with the players but with the clashing owners of big-market teams and small-market clubs.

“I liked Rob from the beginning because he’s very smart, a very good lawyer, and he understood what we needed to do with all the political ramifications,” Selig says. “It’s not like you’re representing a company where the interests are similar. Here you are representing franchises that are stunningly different.”

Selig tasked Manfred with some of the most difficult work.

For example, Selig for years stubbornly insisted MLB didn’t have a steroids problem. After the scandal broke, some fans’ first impression of Manfred was watching him testify before the congressional committee investigating the steroids crisis and acknowledge MLB had been slow to act after ignoring obvious warning signs.

“In a perfect world,” Manfred told the committee, “[we] should have been aware of the use of steroids from the minute it became an issue among the players. Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world.” Manfred says Selig “definitely, over time, gave me projects that I think he thought he was giving to the right person … but it also broadened my portfolio in a way that made me more viable as a candidate to be commissioner.”

“I did yell at him all the time,” Selig says.

As Selig’s deputy, Manfred’s biggest challenge — and one for which he received widespread criticism — was managing MLB’s down-in-the-mud investigation of the Biogenesis clinic in Miami, whose clients were steroids-using players who had escaped testing positive. The scandal led to MLB’s record-setting steroids punishment of Alex Rodriguez and suspensions for 17 players in all.

MLB was accused by the Florida Department of Health of impeding its investigation into Biogenesis and its founder, Anthony Bosch, by purchasing stolen records, including some from a man who went by the nickname “Bobby from Boca.” State investigators said the limited scope of their inquiry was directly related to the records purchase, which they said the league had been warned about. The league spent more than a year and used some three dozen investigators in pursuit of clinic records and potential witnesses. MLB also secured a cooperation agreement with Bosch in exchange for records and testimony.

At the time, Manfred defended the inquiry in a “60 Minutes” interview and said MLB had not paid Bosch for his cooperation.

Asked whether he now regrets the way the inquiry was conducted with nearly a decade of hindsight, Manfred cited the bad behavior of some MLB investigators, including one who wooed the girlfriend of a potential witness with gifts. The league’s investigative team was reorganized as a result. “There were things that some of our investigators did that led to their ultimate departure from the organization,” Manfred says now. “I did not condone that behavior, nor did the organization — it was completely and utterly unprofessional and inappropriate — and that’s why they were terminated.”

But Manfred says MLB lacked law enforcement authority to investigate “an existential threat to the game” and that “our fans demanded that we do everything possible to defend the integrity of the game. And I think we acted in an effort to fulfill that expectation.”

As for the decision to buy evidence and strike a deal with Bosch, Manfred says he had “only two options: You either convince them with the force of your logic to cooperate — or you make a deal with them. They were not prone to be persuaded, and so we made the deal to get to the bottom of what we felt was a really corrosive system.”

In the wake of the investigation, Selig promoted Manfred to chief operating officer. It was a way to burnish Manfred’s credentials and get him more exposure with the owners. No one knew more than Selig about Manfred’s ever-widening portfolio and down-to-earth demeanor, but many owners were unfamiliar with him. (George Steinbrenner, who died in 2010, didn’t even know what Manfred did; the Yankees boss thought he was an accountant.)

Then, in August 2014, at the league meetings in Baltimore, Manfred made a pitch for the top job in a lengthy, forward-thinking presentation to the owners. Even then, he was pushing to change baseball. “Our games are getting longer and, in those longer games, there is less action than ever before,” Manfred told them. Among his proposed changes was a pitch clock.

On the first ballot, 10 owners, led by Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, opposed Manfred. Some believed he was too lawyerly and lacked the right temperament. “Selig was a guy who loved to eat hot dogs at the ballpark, loved the game, just exuded that folksy charm,” a veteran owner says. “Manfred didn’t have that — still doesn’t.”

“The naysayers looked at him as just a labor lawyer,” says Atlanta Braves chairman Terry McGuirk. “I don’t know that the industry had a full appreciation for everything that Bud was offloading to Rob at that time.”

Propelled by Selig’s enthusiastic endorsement, Manfred was elected on the sixth ballot, ahead of Boston Red Sox chairman Tom Werner. No easy feat for Manfred: The owners chose him over another member of their exclusive club. “No Bud, no me,” he says. “I mean, no me as commissioner, at least.” Hired as baseball’s 10th commissioner, Manfred represented a smooth succession from Selig but also a quarter-century generational shift: He was 55 years old, while Selig had just turned 80. The owners’ mandate for Manfred: transparency and change the game.

Not long after the new official MLB baseballs were delivered to his Manhattan office, Manfred hopped on a plane to North Carolina. He hand-delivered the first ball emblazoned with his signature to his 84-year-old father, a man of few words. “This is really an unbelievable thing,” Manfred’s father told his son. “I can’t say I disagree,” Manfred says now.

THE YEAR BEFORE Manfred became commissioner, Major League Baseball introduced a rule that let managers and coaches use a video-replay system to challenge umpire calls other than balls and strikes. Every club now had a video-replay review room down the hall from its dugout. But the live video feeds from a center-field camera would prove too irresistible for some dishonest teams to pass up. Soon, an unknown number of MLB teams were using the live feeds to steal signs and find ways to alert hitters to upcoming pitches in real time, with varying degrees of success.

Sign stealing is nearly as old as the game. Nearly 150 years ago, the Hartford Dark Blues, a charter member of the National League, used a sign-spotter hiding in a shed. By 2017, the Houston Astros had advanced the science by banging on trash cans. (To be fair, the Astros also had the benefit of video feeds and advanced analytics.) No one knew about the team’s scheme until former Astros pitcher Mike Fiers revealed it to The Athletic in November 2019 — two years after the Astros’ World Series victory.

Suddenly, Manfred was confronted with another major cheating scandal.

Following MLB’s investigation, Manfred docked the Astros the maximum of $5 million and eliminated four top draft picks. Astros owner Jim Crane fired general manager Jeff Luhnow and manager A.J. Hinch. But Manfred did not punish a single Astros player. Manfred argued that if he had not granted immunity to the Astros’ players, MLB investigators never would have gotten to the truth. Outraged fans and players, including Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner and Cubs starting pitcher Jon Lester, let Manfred have it.

The scandal raised prickly questions about Manfred’s leadership and judgment. If the Biogenesis probe was an MLB inquiry run amok in pursuit of suspensions, the Astros inquiry was the polar opposite: too fast, too lenient and no player suspensions. Should Manfred have done more — and sooner — to stop the pervasive cheating? Players and managers said they had reported suspicions for years to MLB. In several conversations on this subject, Manfred blames the technological advances in sign stealing for outpacing MLB’s antiquated rules. But he also acknowledges he moved too deliberately as the allegations about multiple teams, including the Astros, Red Sox and Yankees, kept coming into MLB headquarters.

He says he was certain the rule-breakers would stop after he issued memos threatening punishment, including one sent on Sept. 15, 2017, just weeks before the Astros’ World Series run. Later, Manfred accused some club front offices of failing to share that memo with their managers and players, including the Astros.

At a November 2017 meeting of general managers about the rule-breaking, a veteran GM recalls that Manfred started “lecturing them,” with a mix of impatience and condescension. “These are well-educated, accomplished guys, and you’re talking to us like we’re kindergartners?” the GM says.

I share this quote with Manfred, who says he was “direct and pointed” with GMs during that meeting about a slew of rules violations. “Frankly, the reaction from your veteran GM is a pretty good indication of the depth of the problem I was trying to deal with,” Manfred says. “If he was worried about my tone rather than the substance, he was missing the point. My view of the world unfortunately was vindicated because at least two people in that room lost their jobs and their careers because they did not take my comments to heart.”

Manfred tells me he had assumed — well, he “hoped” — that managers, GMs and owners who were aware of their teams’ cheating schemes would “self-correct,” a remarkable admission considering Manfred’s front-row seat for the steroids epidemic. “I hate to admit this, but it’s based on a naive belief that our game is populated by people who want to do the right thing,” he says. “They’re grown men. They know the difference between following the rules and not following the rules.”

Owners defended Manfred’s management of the Astros scandal, which they acknowledge hurt MLB. But a few told me that Manfred had become overly concerned with due process while the cheating flourished.

“Could he have done more sooner?” a veteran owner asks. “Of course.”

When he became commissioner, Manfred didn’t have a deputy — by choice, he insists on leading investigations himself — to help him manage the prickliest issues the way he had helped Selig. It would just be him, for better or worse.

“I think the electronics issue … was a complicated issue,” Manfred tells me.

The ever-expanding buffet of technological methods to send signals, such as using Apple Watches, was not explicitly prohibited by MLB rules. “The rules weren’t clear,” he says. “Enforcement was extraordinarily difficult when you think it all the way through.”

But the commissioner’s job is to clarify and enforce rules, even the vague ones. A common refrain from allies and critics is that Manfred is deliberate to a fault — “too lawyerlike,” a former MLB executive says — when confronted with a crisis that requires swift action.

Sure enough, Manfred offers a lawyerly defense for his deliberate reaction, citing the need to give notice before changing and enforcing the rules.

“You have to get people to buy into the idea that stricter penalties are going to be applied,” he says. “It may not always be as fast as people would like.”

But I remind Manfred that he missed an opportunity to send an unmistakable leaguewide message when the Yankees were caught using a dugout phone to send signals during the 2015 season and part of 2016. Manfred fined the Yankees $100,000, a slap-on-the-wrist penalty that was made public only this past April. If the penalty against the Yankees had been much harsher — and had been widely publicized at the time — would it have sent a loud message of deterrence to all 30 teams, including the Astros?

“Look, I think the answer to that question is really temporal,” he says, showing a flash of irritation and not sounding as thick-skinned as he claims. “The Astros were on notice, right? We had issued a set of regulations that not only clarified what exactly was not allowed but also indicating that the penalties … were going to be dramatically different.”

Manfred also rejected widespread calls to vacate the Astros’ 2017 World Series title, arguing it was impossible for a commissioner to retroactively change a result on the field, even a championship run enhanced by teamwide cheating. In a February 2020 interview with ESPN, Manfred said: “The idea of an asterisk or asking for a piece of metal back seems like a futile act.” On Twitter, #FireManfred trended for hours. Two days later, he apologized.

He now calls it one of his biggest mistakes. “I regret it because it’s disrespectful to the game,” Manfred tells me. “I also regret it because I was being defensive about something.”

Last season, Manfred moved with far more speed when confronted with pitchers’ applying sticky substances to baseballs. Offensive numbers cratered. In midseason, Manfred changed the rules to allow umpires to inspect pitchers’ gloves after each half-inning.

“He wasn’t going to wait until the end of the season to do something,” an owner says. “Not this time.”

The Astros scandal has given rise to new arguments in Pete Rose’s third petition for reinstatement, now on Manfred’s desk. The 81-year-old all-time hits leader was banned for life by commissioner Bart Giamatti for wagering on Reds games as a player and manager and then lying to MLB investigators. Rose’s lawyers are arguing that Rose was treated unequally because he was banned for life but the Astros players were spared any punishment.

I ask Manfred whether keeping Rose on the ineligible list is hypocritical in the wake of MLB’s enthusiastic embrace of legalized gambling through lucrative sponsorships and live betting odds now saturating game broadcasts.

“Rule 21, the gambling prohibition, is regarded to be the most important rule in baseball,” Manfred said. “It is the bedrock of ensuring that our fans see fair, all-out competition, unaffected by any outside forces, on the field.”

He says he will hear Rose out. “Pete will be given an opportunity to come in and be heard, if that’s what he wants to do, before I make a decision,” Manfred says.

WHEN I ASK Manfred what he is most proud of as commissioner, he oddly doesn’t mention a single accomplishment. Instead, he cites something he has prevented from happening: Not a single regular-season game has been lost.

“When I came to baseball in 1998, came in-house, my principal goal was to break the series of negotiations — every one of which had resulted in some type of loss of games,” he says. “This one was obviously more of a struggle, but we kept the streak alive, and I think that’s the most important thing for the fans.”

This one was the 99-day lockout. A portion of this season’s 162-game schedule was almost lost, by a matter of hours, before the owners and players agreed to a new five-year collective bargaining agreement on March 10. The word “struggle” is a pretty benign way of describing the owners’ titanic clash with the revitalized, highly motivated players’ union, led by Tony Clark, who declined to be interviewed for this story, and an aggressive, veteran lawyer named Bruce Meyer. The players had lost ground in the past two CBAs and did not want a repeat. The players’ median salary dropped from $1.65 million in 2015 when Manfred became commissioner to $1.4 million in 2019 and was $1.2 million at the start of this season, according to published reports. Average players’ careers also are shorter; as of 2019, players averaged 3.71 years in MLB, according to union data, down from 4.79 in 2003.

Both sides’ profound distrust, aggravated by accusations that owners had colluded and used other devious methods to limit some players’ salaries, worsened in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic raged, ballparks sat empty and a full season appeared to be lost. In June 2020, Manfred assured fans that, despite the pandemic, he was 100% sure there would be baseball. Five days later, he announced the season was in jeopardy.

“I’m not confident,” he said. “It’s just a disaster for our game, absolutely no question about it.”

After meeting with Clark in Arizona, Manfred assured owners he had struck a deal for a 60-game season. But a day later, the union asked for 10 more games and more playoff money, and Clark publicly denied that a tentative agreement had been struck. The owners were furious — with Manfred. After all, he had assured them a deal was done. Publicly, Manfred and labor leaders traded angry accusations of bad faith, and fans became even more frustrated. Finally, Manfred did what he had the right to do months earlier: He imposed a 60-game season, and the union later filed a $500 million grievance against MLB.

Manfred deeply regrets “this public thing” he had gotten into with the players’ union about the players’ insistence that they be paid for a full season with fans. “Stupid,” he now calls it. But he felt he had no choice: “I had 30 [owners] saying, ‘What the hell are you going to say?’ They’re like, ‘Are you a doormat here?'” he says. “My credibility was on the line — with my bosses.”

The harsh criticism from players targeting Manfred was “tactical,” he says, and comes with the territory. “I think that the union did an effective job with the tactic of making me an issue in the negotiations,” Manfred says now. “It resulted in a lot of negativity.”

But Clark and Meyer, the chief negotiator for the players’ union, disputes that players’ public — and private — criticism of Manfred is tactical.

“The suggestion that the players’ negative views of Mr. Manfred were somehow not sincere or were orchestrated by the union is an unfortunate attempt to deflect and avoid taking responsibility for the league’s actions, which the players themselves saw and heard firsthand,” Clark said in a statement.

That kind of criticism gnaws at Manfred, particularly when things that are said or written about him or the game are “palpably untrue,” he says. “Some days you just say, I’m tired of this. Why do I have to listen to this?” But he adds, “I’m a happy person. I literally am a happy person. If I let it gnaw at me, I would not be a happy person. Really, I mean that.”

More than once, Manfred tells me that serving as a human buffer who absorbs most of the heat for his billionaire bosses is a critical part of his job. Few commissioners dare to publicly admit such a thing, even if it’s obvious to many fans.

“Every time it’s me, it ain’t one of those 30 guys — that’s good,” Manfred says. “Look, who the hell am I? I don’t have $2 billion invested in a team. I’m just a guy trying to do a job. I mean it. They deserve that layer. I believe they deserve that layer of protection. I’m the face of the game, for good or for bad.”

NOT LONG BEFORE he ordered the lockout in late 2021, Manfred told me that MLB players have “the best deal” among America’s four major sports leagues: “Only one has no salary cap. Only one has no rights of first refusal, no franchise tags, the most guaranteed dollars. They have the best pension and health and welfare plan. Everything they have is the best in sports right now.”

And as the lockout loomed, Manfred said: “There’s only one kind of loss in labor — that’s no deal. If there’s a deal, it’s always a win.” For his bosses, a new CBA resembling the previous two, in which the owners torched the players, would be a mammoth win. But the union leadership was determined to roll back an array of the owners’ economic gains.

During the first 43 days of the lockout, the prospect of a deal looked unlikely because the two sides didn’t meet once. Players expressed anger at the process — MLB infuriated players by scrubbing all the players from the league website when the lockout started, a union source says — and at Manfred, in particular. The bad blood reached back to his clash with the union over the pandemic-shortened season and his remark that the World Series trophy was “a piece of metal,” union sources and players say.

“If you want to turn a group of 1,200 players against you, it’s comments like that,” says Andrew Miller, a 37-year-old just-retired veteran pitcher who had a seat at the bargaining table last winter. “Our union leadership doesn’t have to tell 1,200 guys to be upset. When that headline takes over, it’s a pretty good way of essentially creating that dynamic and frustration and feeling that you don’t appreciate the game. I think most of us would like to assume Rob has some appreciation for the game.”

“What has he done to show the fans that he loves baseball?” Red Sox pitcher Rich Hill told the Boston Sports Journal in February. Hill accused Manfred of “killing the game … Ten years from now, we’ll say, ‘Jeez, what happened to baseball?'”

Manfred did not attend any bargaining sessions until late February because he decided to defer to Dan Halem, MLB’s deputy commissioner and chief legal counsel, as the lead negotiator. That’s when both sides hunkered down for a week inside a conference room overlooking the field at Roger Dean Chevrolet Stadium in Jupiter, Florida. With the first hard MLB-imposed deadline approaching, the economic divide was narrowed.

Manfred was certain that both sides were on the verge of striking a deal on Sunday night, Feb. 27, less than 48 hours before he announced the cancellation of the regular season’s first week. What Manfred says he didn’t count on were details from the talks immediately leaking on social media from some players, agents — and even a few baseball writers who took to Twitter and other platforms to trash a deal they said or suggested was bad for players.

With growing fury, Manfred watched the criticism play out on his cellphone. In his view, the social media opposition helped harden players’ resolve against a deal that had seemed within reach. Then came the postponing of Opening Day, and that smile.

When I visit Manfred at MLB headquarters shortly after the CBA was signed, he bounds into a conference room, plops himself in a chair and immediately launches into a rant against players and unnamed media members he says embraced the union message. “You’re supposed to cover the story — not be a part of the story. I mean, I’m not a journalist, but even I know that. I think that’s kind of Rule 1, right?” Manfred says.

Manfred then describes a recent chat with Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh about the way social media impacts labor negotiations in real time. “I feel like a f—ing dinosaur,” Manfred recalls telling Walsh. “Rob,” Walsh replied, “social media has changed bargaining.”

Meyer, the union’s chief negotiator, says a deal was far from close then and that Manfred’s “version of events is completely and utterly false. It bears no relation to reality.” Meyer says that on Feb. 27, he had told Halem, MLB’s chief negotiator, the players were still far apart on several key economic issues. “That night we heard the league was trying to convince the media that we were close to a deal,” Meyer says, adding that the union had to deny those reports. The suggestion that social media chatter by players or media members had killed an imminent deal “was totally made up,” he says. “A clumsy and obvious PR strategy to put pressure and blame on the union.”

Only a week after Manfred’s smile, and with more games in danger of cancellation, MLB’s final proposal was ratified by the union, 26-12. All eight of the executive subcommittee members voted against it, but the union’s rank and file voted 26-4 in favor. Manfred now says a 162-game season was saved by a matter of hours. Among the highlights: The players’ minimum salary was raised to $700,000, the postseason was expanded from 10 to 12 teams and the competitive balance tax that serves as a threshold for total team salary was raised. Teams that exceed the maximum total — $230 million this year — must pay luxury taxes. A final hurdle for the owners was overcome when the union relented on the rules changes, allowing Manfred the leeway to make those changes.

From the union’s perspective, historic economic gains were made, including the largest single-year increase in minimum salary. Manfred punts on the question of whether his bosses believed they had gotten the better of the union again, though some owners are pleased that the players didn’t walk away with even deeper economic gains. “Look, I don’t think there was one side that won,” Manfred says. “It took too long, probably, it was a little unsightly, but the parties compromised and reached an agreement that I think is going to be good for the game over the long haul.”

No matter how they see the CBA’s fine print, owners seem thrilled with Manfred’s job performance. And why wouldn’t they be? Despite its array of problems, league sources say baseball has grown into a $10 billion-plus-a-year sport, up from $8 billion when Manfred became commissioner. Owners also loved Manfred’s reorganization of the minor leagues in 2020, and in the past decade, franchise valuations have more than quadrupled. Not surprisingly, billionaires want in, and expansion is coming. “I would love to get to 32 teams,” Manfred tells me.

And the owners have rewarded Manfred with a $17.5 million annual contract — plus performance bonuses, the pay package has exceeded $25 million — that expires after the 2024 season.

“Rob is a relentless guy focused on success,” says McGuirk, the Braves chairman. “There are very few down days looking at the business of baseball with Rob at the helm. If we had to sign up for him again, we’d do it in spades 10 times over.”

ALMOST BY ACCIDENT, Manfred found an eloquent crusader to help improve the game. In September 2020, Theo Epstein wrote a lengthy letter to Manfred. It was a kind of manifesto outlining Epstein’s ideas for rule changes that would transform the game by transporting it, time-machine-like, to its not-so-distant, faster-paced and more fun past. “All change doesn’t always lead to something new,” Epstein says. “Change can also be restorative in certain ways.”

Manfred liked Epstein’s letter so much that he hired him as an MLB consultant.

“He doesn’t want to be a slave to tradition, and he is determined to modernize the game in an important, effective way,” Epstein says. “But he also doesn’t want to reinvent the wheel and make change for change’s sake and betray the history of the game.”

Nearly three decades ago, the average MLB hitter batted .265; today the average hitter bats around .240. The strikeout rate in 1980 was 12.5%; last season it was 23.2%, and this season it stands at 22.2%. Epstein says that through the first half of 2021, the strikeout rate was higher than it was during the careers of fireballers Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens. “It shouldn’t be scandalous to try to recreate the equilibrium … that we all became accustomed to when we fell in love with the game,” Epstein says.

The surest way to recreate that equilibrium is the pitch clock, proponents of the rule change say.

A pitch clock would give a pitcher 14 seconds between pitches with no runners on base; 18 or 19 seconds with runners on. There’s now an average of 23.8 seconds between pitches. With the help of testing and refining the pitch timer in its minor leagues laboratory, MLB projects a pitch timer would shave an average of 30 minutes off game times, getting close to fans’ “ideal” of 2 hours, 30 minutes. Manfred says the pitch clock represents one of the best ways for baseball to better compete in a world of countless entertainment options and ever-shrinking attention spans.

Purists, and some players, hate it. The game’s poet laureates, from Angell to Updike, have waxed lyrically about the timelessness of baseball, the only sport without a clock. And scores of high-profile veterans despise the idea. “I think baseball is a beautiful sport with fewer rules,” Miller told me. “Something about a clock on a baseball field just doesn’t feel right.”

Epstein agrees that introducing a pitch clock is “a scary concept … I didn’t love it when I first heard about it 10 years ago.”

But the pace-of-play results have seized everyone’s attention. In the low-A West league last season, the pitch clock shaved 21 minutes off average game times. Even more striking, the league had the second-highest scoring average in minor league baseball, a seemingly incongruous correlation between shorter games and more scoring, the sweet spot that Manfred seeks. Perhaps even more surprising, players, managers and fans enthusiastically embraced it. An internal 2021 MLB survey shows all the rule changes introduced in the minors had become more popular by season’s end — and none more than the pitch clock.

At an owners meeting in Orlando, MLB executives showed a side-by-side video of minor league and major league games, one with a pitch clock and one without. Owners were flabbergasted by the difference. “I couldn’t believe it,” says DeWitt, the Cardinals owner. DeWitt and most, if not all, of his fellow owners are so frustrated by the game’s plodding pace that they can’t wait for the pitch clock to be introduced. “I think some owners wouldn’t mind if all games were just seven innings,” Manfred says. “That’s certainly not high on my agenda.”

Another side-by-side video, with Epstein doing the voiceover, compares a two-batter sequence in the minors and majors. Both clips included a three-pitch strikeout and a five-pitch walk. In the big leagues, the sequence was 45 seconds longer. “If you extrapolate that over an entire game, it was 28 minutes longer,” Epstein says. “You don’t just save time — pitch-clock games are like games from the ’70s and ’80s … There’s a great natural rhythm; it’s the way the game is supposed to be.”

And then in what could be the slogan promoting the pitch clock, Epstein says: “A pitch is not supposed to be a 30-second spectacle.”

Video feeds show that fans behind home plate at MLB games are often distracted by their cellphones, says Morgan Sword, MLB’s executive vice president of operations and one of Manfred’s leading “believers” in the pitch clock’s beauty. In the minors, fans appear more focused on the action because with a pitch clock, if you look away for long, you are more likely to miss something. A pitch clock also keeps more fans in their seats deeper into games. “Think about the casual fan. You get to the two-hour mark and you’re in the top of the fifth,” Sword says. “And you look at your wife and say, ‘We’re not staying for this whole thing. Why don’t we just get out of here?'”

Umpiring reforms are another path to a faster pace.

The average time for video-replay reviews of umpire calls this season is 1 minute, 37 seconds, up 21 seconds from last year. In 2024, Manfred says, the automated ball-strike zone system, or as it’s commonly called, “robot umpires,” will likely be introduced. One possibility is for the automated system to call every pitch and transmit the balls and strikes to a home plate umpire via an ear piece. Another option is a replay review system of balls and strikes with each manager getting several challenges a game. The system is being tested in the minor leagues and has shaved nine additional minutes off the average game length this season, MLB data shows. “We have an automated strike zone system that works,” Manfred says.

He declines to grade the MLB umpires’ overall performance this season — fans are displeased, to put it politely — and he insists the adaptation of robo-umpires should not be seen as an indictment of their abilities.

The changes Manfred wants appear to be a foregone conclusion. Under the previous CBA, Manfred had the right to unilaterally change the rules one season after giving the union notice. “Mostly under my leadership,” he says, “we have been deferential to a fault in terms of trying to make changes in the game,” a delay that has aggravated many owners. Now, Manfred has the right to change the rules 45 days after approval of a new competition committee, which will have its first meeting in 2023 — a formality since the committee is tilted to the owners.

Still, Manfred is seeking wide consensus. He has embarked on a leaguewide campaign to convince the players that the coming changes are what’s best for the game. Already, he has visited half of MLB’s clubhouses to answer players’ questions and try to win support for the rules changes, especially the pitch clock.

Former MLB star Raul Ibanez, MLB’s senior vice president of on-field operations, joins Manfred for the clubhouse sessions. “They’re the experts on the field, and getting their perspective and feedback is important,” Ibanez says. “When players walk out of the meetings, the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive.” Ibanez refused to discuss how many players have expressed opposition to the pitch clock and other proposed rules changes, though sources say some players are adamantly opposed. It’s a challenge for Manfred, in part, because of how some players view him and his motives. “I can’t tell you how many times I heard from club people, players, the people that work for us, that the players hate Rob,” says Halem, the deputy commissioner. “It’s just like how the union has positioned this with the players — all your problems in life are that guy in New York that doesn’t like baseball.”

Manfred denies the notion that every rule change is being driven solely by him. “This is not a Rob Manfred crusade in terms of the game,” he says. “These are not personal views. These are, you know, research-driven views that any business would have to pay attention to.”

As Halem says, Manfred now needs to be a salesman, an evangelist for baseball’s future. His campaign will require a mix of diplomacy, persistence and a soft touch. “I think I have tried to be positive about our game,” Manfred says. “I think the tough spot is, even if you love something, if you recognize that change needs to come and you talk about that, people take that as negativity. I don’t see it that way. I see it from the perspective of, ‘I love the institution, I love the game and I want it to be everything it can be.'”

ROB MANFRED AND I are walking side by side in the whisper-quiet Baseball Hall of Fame, past the bronze plaques that honor nearly a century of the game’s immortals. It’s just past 9 a.m. on the day last September that Derek Jeter and the class of 2020 will be inducted into Cooperstown.

We have the place to ourselves, and the commissioner is in an expansive mood. As a man who embraces his role as guardian of the game, he talks often about the “institution of baseball” as central to American culture — and how it’s important that he and his colleagues get every change exactly right. A failure to protect and preserve baseball could hurt … America.

“If you make a mistake on the guardianship of the game, you undo or damage a part of our culture that I believe is significant,” he tells me. “And significant in a way that’s different, with all due respect, than other sports.”

“I see the institution of baseball as significant to American culture.”

Manfred says nothing is more important than introducing baseball to the next generation of fans. Baseball needs young people, and Manfred is trying to stoke the love affair. “I hope that we undertake initiatives that result in baseball being passed down to the next generation,” he says, “the way it was passed down to our generation.”

Quietly, he has invested tens of millions of dollars of his bosses’ money introducing baseball to young people across America. Manfred says playing baseball as a kid is “the No. 1 determinant of whether somebody’s a fan, as an adult.” The investment of $40 million a year — an increase of 500% since Manfred became commissioner — is the “best money we spend every year,” he says. Former Angels executive Tony Reagins, whom Manfred hired as chief baseball development officer, says the investment has already yielded results in growing the game among children.

In all my conversations with him, Manfred repeatedly talks about pushing to evangelize for the game in his own way, even as he keeps answering, or ignoring, the critics.

Last year, Manfred was blasted by some for his decision to move the 2021 All-Star Game from Atlanta to Colorado after Georgia officials passed a voting law that opponents say was aimed at suppressing votes among minority voters. McGuirk, the Braves’ chairman, called Manfred’s decision “a punch to the gut … I didn’t get what I wanted. My franchise took a loss.”

Then this May, a Georgia primary had a record early turnout. Critics said it was proof that MLB made the wrong decision moving the All-Star Game out of Atlanta, which cost the city more than $100 million in tourism revenue. “At the end of the day, it was my decision and my responsibility,” Manfred says of moving the All-Star Game, denying he was motivated by any outside pressure.

“With the facts that existed at that point in time, I think I would make the same decision,” he says. “I have to say, we’ve now been through an election cycle in Georgia. I’m glad there was a big voter turnout. I know that some people will say that proves that you were worried about nothing. I think the other way you look at it is, maybe we brought attention to an issue that people turned out in bigger numbers because of that attention. I don’t know what the answer is. I do think that in the same context, I’d make the same decision.”

And there are ongoing questions and complaints over whether Rawlings, now co-owned by MLB, is purposefully modifying the manufacturing specifications of the baseball, either to juice or deaden the balls. Nope, says Manfred: “Our baseball is a handmade product. … There is always going to be a variation, baseball to baseball, because it’s natural materials and it’s made by hand.”

Many fans also complain that too many networks now broadcast MLB games, many behind paywalls. Fans say games are difficult to find and access, and blackout rules remain an irritant. “Our No. 1 business priority right now is reach,” Manfred says. The topic was a main discussion at an owners meeting in June. “Believe me,” he says, “we hate blackouts as much as fans do.” Manfred notes that the blackout clauses are written into broadcast deals — which he has overseen — but he says it’s now a “top priority” for MLB to phase them out.

After the 2024 World Series, Manfred’s current contract will expire. He’ll be 66 years old.

“I really haven’t made a decision about what I’m going to do, whether I want to continue,” he says. “You know, I love the job. But I haven’t really made a decision about what’s next.”

Later this summer, Manfred will complete his leaguewide tour of team clubhouses, seeking acceptance of a new game that’s coming. “If he had a track record of being upfront and honest, players might trust him more and not have to question his actions,” Miller says. “That’s not where we’re at.”

It’s not just the players who need to buy into the Manfred doctrine. So do fans.

“Sometimes we actually fight with him on some of this stuff,” Halem, the deputy commissioner, tells me. “Most of the time the public sees him … it’s all about conflict and fighting or defending scandals or bad stuff. And it’s just very difficult when it’s your job to defend clubs, defend owners, and that’s the way the public is seeing you.”

Does Manfred feel misunderstood by fans? He pauses before answering.

“Oh, I don’t know what I think about that question, to tell you the truth. I think like every human being, I would like people to have a positive impression of me and the job I do,” he says. “But I try not to worry about what people say too much because you get caught up in that, and it affects your decision-making process.”

As for how he hopes to be remembered as a commissioner, Manfred says simply, “I want to make sure we get baseball back to at least where we were, if not even better.”

But, he adds with a laugh, fans will probably recall him as “that crazy guy in New York” who couldn’t stop messing with baseball: “That’s going to be on my tombstone: ‘He tinkered with the game until they got rid of him.'”

Don Van Natta Jr. is a senior writer at ESPN. Reach him at Don.VanNatta@espn.com. On Twitter, his handle is @DVNJr. ESPN’s John Mastroberardino contributed to this report.